The story of “Sonoramic” (long ram induction) MOPARs – by Joe Godec

Courtesy of the Plymouth Bulletin.

By the mid-1950s, Plymouth’s reputation as a very reliable family car was long and well established — possibly too established and too doughty at a time when the new interstate highway system was bringing about tremendous changes in commuting patterns and intercity travel. In the middle of the Twentieth Century, virtually all cars could boast inherent reliability, so the car-buying public began to look for new selling points from the auto industry. “Engineering” was now beginning to replace “reliability” as a watchword, and “Chrysler engineering” soon became more than a sales pitch.

While Plymouth now had V-8 power (with157 bhp/240 CID, 167 bhp/260 CID, and 177 bhp/260 CID versions), it wasn’t until the introduction of the Fury in 1956 that the marque began to shed its staid image. Actually, when a 1956 Fury hit 124.611 mph at Daytona (on the sand, no less), the Ford and Chevy fans were served notice that a new kid had arrived on the block and he wasn’t going to be bullied by anyone. What’s more, the magnificent ’57 and ’58 Furys kept up the pace.

The standard engine for these Furys was a version of the “polyspherical” engine, itself a derivative of the original hemispherical (or domed) combustion-chambered power plants dating from 1951. While the old Hemi became the darling of the hot-rod set, the “poly” somehow found itself relegated to the back streets of the automotive world in spite of being able to put out 290 bhp in its ultimate ’50s form, perhaps because it was so much bulkier and heavier than the contemporary FoMoCo and GM offerings. And even the Fury itself, cursed with Plymouth’s reputation as being a great car for an old-maid school teacher or the company car of a traveling salesman, didn’t quite have the reputation enjoyed by its big brothers, the 300s, the D-500s, and even the Adventurers.

Much of this was Chrysler’s fault as not only they never seemed to want to put that big Hemi in the Plymouth, but also they really didn’t seem to want to develop the “Poly” either (that would have to wait until the late ’60s and early ’70s).

The labor problems of the late 1950s and the engineering problems of the rushed 1957 models had dealt the Corporation’s reputation for quality a staggering blow and the AMA ban clobbered its performance and youth image. All roads from Detroit lead to the “bottom line,” so quality could be, and was, addressed by industrial relations, but performance engineering had to be resuscitated. Chrysler may have had “The Banker’s Hot Rod” in the 300, but how many bankers ever cruised Main Street on a Saturday night?

There was never any question that any of its divisions would ever be allowed to flat-out defy the AMA and storm back into racing, but Chrysler did have that reputation for engineering innovation to uphold. Performance development (that phrase lends itself well to obfuscation) was a legitimate venue for engineering innovation, and with 1960 came some of the most radical automotive engineering of all time: RAM INDUCTION!

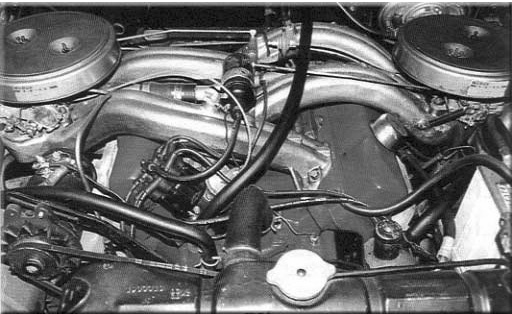

It now seems as though it were ages ago, but I shall never forget the absolute sensation that those first cross-ram manifolds caused. Every car magazine, and I do mean every car magazine, had a feature on those engines and manifolds just as soon as the new models for 1960 came out, and most followed up with test articles later. By any standard, the engines were imposing — the B series block (itself a monster) with two separate 30-inch aluminum manifolds, each manifold sporting a four-barreled Carter AFB, one manifold looping over the left valve cover almost to the left fender well (but feeding the right cylinder bank) and the other going from the right fender well over the right valve cover to feed the left cylinder bank (hence “cross-ram”). “Crazy!” “Weird!” But it worked; it worked well.

Chrysler had been experimenting with what is technically called a tuned induction system for a number of years — the engine on that Indy car had “Tuned” stacks for its Hilborn fuel injection — and it had even taken out a number of patents on what would be the “SonoRamic” principle in the late 1940s, so the engines just didn’t materialize in time to come on the showroom floors on October 1959. In fact, some of the younger guys working on these kinds of projects were performance buffs in the truest sense; in the mid-50s, with a few other kindred spirits working for or with Chrysler, they even started a car club of sorts that had a catchy name based on this principle of “ram induction.” They called themselves “The Ramchargers.”

Since I’m not an engineer, I had to have this whole thing explained to me very slowly a considerable number of times before I even got to the stage where I could nod authoritatively at a few points to at least give the appearance of knowing what was going on. But the way I understand it, it works much like water flowing through a pipe in that the water wants to keep moving even after a valve or faucet is closed. Sometimes, this water even “hammers” when it begins to pile up against the valve. In the “SonoRamic Commando,” the fuel/air mixture in one of the tuned arms of the manifold works somewhat in the same fashion in that the principle of fluid dynamics wants to keep it moving even though the mixture is obstructed by the closed intake valve. In effect, then the fuel/air mixture is literally “rammed” up against the closed intake valve of the engine, instantly available to charge the combustion chamber when the valve comes open. This is the “Ram” part.

The “Sono” comes from that compression wave that the service manual talked about. Through the mysteries of modern science, those 30-inch passages were carefully designed to maximize the resonant effect of that compression wave so that it hits that intake valve at the very instant it is opening for that fuel/air mixture that already has been rammed up against the valve. This provides an additional force to push more of the fuel/air mixture into the combustion chamber until the valve closes.

The kicker in this equation is that the passage length of the manifold directly affects the rpm range at which the optimum boost is achieved. Since these compression waves move at some 1100 feet per second, if you want your maximum boost at the middle range of engine operation, the tubes have to be longer for the wave to take more time to get out and back in sync with an intake valve opening to give a maximum boost at 2800 rpm. If you want that engine to scream at 5000-5500 rpm, the passages have to be shorter as you want that wave to get out and come back quicker.

Initially, the Plymouth version was supposed to be just the 361 CID mill and it was rated at 310 hp/435 ft. lbs torque (interestingly, the identical engine for the newly introduced Dodge Dart came out at 320 hp, but Dodge was the big brother and must have been entitled to the ten extra horses because of seniority). This engine option added a hefty $389 to the base price of any car, plus the additional $211 for the necessary Torqueflite transmission.

One of the lesser-known options, and one which can really be confusing, is that there were some of these long (30″ manifolds) that had internal or “tuned” passages that were only 15″ long. On these manifolds, the external valley on the arms goes only from the cylinder head to the area just above the edge of the heads in contrast to the standard ram tubes on which the depression indicating the internal wall runs from all the way to the carburetor from the head. These “short” rams were the ones intended for higher rpm boost and are very rare. They produced 340 horsepower in 383 CID engines.

Of course, torque is what gets a car off the line in a hurry and Ram Induction increases available torque. Note that the SonoRamic 361 produced 435-foot pounds of torque at 2800 rpm. The “Golden Commando 395” (the 361 with a single four) gave out only 395 foot-pounds.

The SonoRamic Commando soldiered on through 1961 when the 361 CID version was dropped and the 413 introduced, having 375 horsepower with the “long” tubes (the very few ones with the “short” tubes were listed at 400 hp). Chrysler had developed a three-speed manual for their big engines, and ram cars could be found with the conventionally mounted column shift gear shift lever, but a properly set up Torqueflite generally could outperform the manual because of its ability to “out-jump” the manual at the start. With the 413, the Plymouth was a fire-spouting monster and the Ramchargers had hoped to use one as their stock drag car that season. However, the division’s management had a jaundiced eye toward drag racing, so the group drifted over to Dodge which was more responsive to its overtures.

In any guise, the old SonoRamic Commandos were awesome performers. The most famous was one driven by Al Eckstrand to Super Stock Automatic honors at the 1960 National Hot Rod Association national meet at Detroit during the 1960 Labor Day weekend to beat out a “Super Duty” Pontiac from Royal Oaks Pontiac (Jim Wangers’ outfit), with a winning elapsed time of 14.51 seconds and a speed of 97.82 mph.

Shortly after he bought one of these great machines, I was very fortunate to “appropriate” one from my dad (it is one of the family legends how he lost it and I got it, but that’s another story). I drove it while in college and lived like a character from American Graffiti. After I put some 4.10 gears in the rear end and a set of Hedman Hedders on the engine, that car would surprise even 409/409 Chevys at a “Stop Light Gran Prix.” I couldn’t wind it as tight as the Chevys (either the 335/348s or the 409s), so they would start to scream past me after a couple of blocks or two-thirds of the way through the quarter mile, but off the line . . . WOW!

Today, not many of these big-tailed beasts and their 1961 cousins are still around (possibly no more than a dozen or so from both years). In fact, AutoWeek stated in a 1995 article that no more than four or five hundred total were produced in those two years; and while the historical folks at Chrysler have all kinds of information on individual cars, they can’t say how many ram-inducted Plymouths were made.

1960s Plymouth Plumbing Image 2

Cross rams in cross-section. These baby’s were huge – and luckily cast in aluminum. If you wanted torque, they worked!

1960s Plymouth Plumbing Image 4

Golden Commando Emblem – it could mean 2 4-barrels on a regular dual plane minifold. You needed . . .