Made In Pontiac, Part 4

by Eric White, Reprint with Society permission only

Wild About Cars: Was there an area where they built the special cars?

Carl Papke: There was a Quonset hut in the back end of Plant 8 that they called the “100% rack.” They would pick cars out at random and take them to this Quonset hut. There was room for probably six cars in there. They would pull a car in, raise it up in the air and they would visually inspect every piece on that car. That’s why they called it the 100 % rack. This was above and beyond anything done on the line.

Mind you, only maybe one in a hundred, or perhaps one car an hour coming out of the back of the assembly plant, in no special order, would get picked. They would check everything on that car. They would match them against the manifest to see that everything on that car was correct. They would do this to determine what percentage of cars were getting out with defects nobody caught.

Now you had inspectors in the plants. Every thirty or forty jobs there was a line inspector. He would check all of the other jobs that people had done before him. He would write down, chalk mark, spray paint, anything he could to identify it so that repair in the back end would know that there was a problem. But, the 100% rack was something that was totally beyond that. This Quonset hut checked this car after it was ready to go. Everything was supposed to be right.

A friend of mine, Dennis Long, worked down there. He lives down here to Clifford now. He ordered a ’65 GTO, two-door hardtop, Bristol Blue in color – which was a special color – 389 tri-power, close-ratio four-speed, 3.90 positraction rear end. It had a white interior. When he followed his car through as they built it, his supervisor had them take that particular car out and put it on the 100 % rack. When they did this, they found out that it had one shock on the back that was wrong. They found out that it had the wrong drive shaft in this car. There were a few other minor little things that were completely wrong on this car that nobody had caught. The inspectors hadn’t caught it. Chances are he would have driven it down the road and never knew why one side sat a little lower in the rear. Wrong shock.

He had watched this car being built. You can’t check this because you wouldn’t know if there was something wrong being put on. That’s what they did in that Quonset hut. They changed complete motors out there. They changed transmissions out there. They changed rear ends out there. If they got a car in there and something was wrong on it, say it had a defective carburetor on it, they would probably change the carburetor. But if it was an air-conditioned car they’d be more apt to pull the intake and carburetor off together and put a whole new unit on because it was easier.

They did whichever way was the fastest. If they had a motor that had a bad head on it, maybe one of the spark plugs was twisted off, or something of that nature, instead of pulling that engine down and changing the head, they would pull the whole motor out, put a complete new engine in it, and send that damaged motor back to final repair. Them guys would either repair it, and then it would be installed on the line at a later date, or they would disassemble that and split the parts off. They would go to service parts.

Maybe the whole motor would go for a service engine someplace. Another thing you hear a lot of people talking about – for a car to be correct, the engine has to be built, they say, from thirty to ninety days before the production of the body. That is only a “house rule.” That’s not pat. I’ve seen the train cars come in with a whole load of Pontiac motors that had been setting with dust on ’em and bird manure all over ’em. These engines had been setting probably six months someplace. And they were going to get put in production-built cars.

Nowadays, with that particular engine on a GTO that some guy was restoring, or somebody else was seeking to buy, they’d say “look, this motor was built nine months before the build date on this car, that’s not right.” That could very well be the correct motor for that car. That would probably happen later on in the year, but it could happen anytime. An engine that was into production early in the model year could have had a defect in it. They set it aside, it got shoved around for two months before it got repaired, then when it did get repaired it come back into the production line, and maybe it sat around another two months before it was to be used. Now there’s four months difference in there.

WAC: On the other hand, if a car was being assembled in the mid-part of the model year, say between Christmas and springtime when you guys were running seventy to eighty units per hour down the line, might there only be a day or two between the engine casting date and the body assembly date?

CP: It could be down that close. A core could come out of the foundry. It’d be put through Plant 9 and be put into a car as close as three days to the build date on your car. If they were running right down – and maybe they were shipping a lot of motors out of Plant 9 to another plant someplace – they could have shipped all of their overstock and they were running right down almost one for one, and it could be three days. It could be two days even. It doesn’t take long to run a block through. From the time a frame was set on the line on the first floor of Plant 8, until a completed car rolled off the end of the assembly line, I would say roughly two and a half hours had gone by. It was a bare frame, and two and a half hours later it was GTO-pretty. Ready to run.

WAC: Ready for Carl to jump in and tear off for Plant 16?

CP: Ready for me to get it, yes. They also had an area in the plant near the end of the line where there were huge rotating drums buried into the floor, and they would pull the cars on there, and they had gauges that set up in front. You could sit in the driver’s seat and completely simulate highway use. It would set right there locked into one spot. Them guys would run them cars through the gears.

There was a speedometer display, and they’d run it up to sixty and back down to zero. If you got on it the tires squealed just like they did on the road. If you hit the brakes they squealed like they did on the road. But the only thing that was moving was the back wheels. They did this to every vehicle that come out of Plant 8. They would fill them full of antifreeze, put three gallons of gas into ’em, and they went about thirty feet and were started. There were four guys there, and they all had a spot and they would shuttle them and drop it off in the right spot and the guy would get in that car, fire it up. Amazingly, it would start fast.

WAC: That wasn’t the first time that the engine had been fired up.

CP: Nope. That engine had been run over in Plant 9. It had been run without a carburetor on it. They had a hose with an air-natural gas mixture that clamped down onto the intake, and the engine would run just as if it had a carburetor. They could push buttons and rev these motors up and run ’em at a certain rpm. After they got done they’d pull the hoses off the water connections, disconnect the plate from the intake and send it on its way. I had a lot of motors come up into Plant 8 on the second floor, on the motor bridge, warm from where they’d been running, and they did not have a carburetor on them.

WAC: How long was that initial run in?

CP: They’d run that engine maybe thirty seconds. They were checking for balance, for performance. They wanted that motor to run. They wanted it to have oil pressure. They wanted it to warm up. They wanted it to basically run like it should. They had gauges and machines and lights that told them all of this. If it failed, it didn’t get out. That’s what the roundtables were for. There were two of them. They would run these motors. There were several guys up in the center of it, they’d be putting engines on and pulling ’em off. As a guy got done running a motor, they would pick it off, they’d turn around and hang it on the line and it would come right on up into Plant 8.

When they came into the motor bridge, there was a bank there where the line just went back and forth for about twenty-five yards. Them engines would be side by side hanging on racks probably five inches apart. You couldn’t walk between them. There’d be maybe two hundred motors stored there. That’s so if something happened in Plant 9, instead of shutting Plant 8 down too, they had a couple hundred motors in reserve. They could keep Plant 8 running three or four hours. It was just a build-up area. They had a lot of different areas where they had stored rear ends, transmissions, motors, but they all came together at the right time.

WAC: How computerized was the plant at that time?

CP: At that time I don’t even remember a computer. If they had them, they were in the front office. Somebody besides me knew about them.

WAC: How were the different plants coordinated?

CP: I couldn’t tell you how they did that. I don’t know who decided which manifest went on this motor and what motor went on that hook. One of the things that would set in the plants in each area and each department was a machine two foot square, three foot high, and it would spit these manifests out. They would come out like an automatic typewriter; like a teletype machine. They were controlled from one main point.

At the same time these would all be running. They’d be dated at the starting of that shift, such and such, job one. You grab that manifest and you stuck it on the motor that was waiting. It was right there. The next manifest was to the next motor. That’s as close as I can tell you as to how they coordinated it. Nobody in the plant used a computer.

WAC: What was on the engine as it came onto the motor bridge?

CP: The water pump was on the motor. The basic motor was complete when it came up onto the motor bridge. It didn’t have a starter, but it did have a flywheel on it. It had exhaust manifolds on it. It had an intake, tappet covers, water pump, harmonic balancer and the pulley was there. Anything that was painted blue was on it. The exhaust manifolds were on it, but they weren’t painted.

WAC: I’ve read that the Mopars and Chevys got their exhaust manifolds oversprayed engine color, but Pontiac didn’t paint their exhaust manifolds because they didn’t like their customers smelling burnt paint. Is there any truth to that bit of lore?

CP: I don’t know about Chevrolet or Mopar. Pontiac I can tell you didn’t have paint on their exhaust manifolds. I don’t know if it was because the customer didn’t like the smell of burning paint, but I know that they did not paint the exhaust manifolds. They were cast iron color.

The chrome tappet covers came up on the engine, and they would paint them blanks down in Plant 9. They would just set like a fiberglass blank down over the tappets, spray that engine, then pick it off. Then they’d put the chrome tappet cover on. The oil filter was on the motor and that was over-sprayed. But not a lot, maybe on one side. There was places on that motor that was bare.

It didn’t matter to them if there was a spot that didn’t get paint. Like on the bottom of the intake manifold; they didn’t get down in between there on the valley cover. Basically they painted it, it was going to get hot, it was going to burn off, and they weren’t overly concerned. They didn’t worry about getting X amount of ounces of paint onto a motor. If it didn’t get paint, it didn’t get it. The motor mount got put on just before the starter. That was one of the later procedures. The motor mounts got put on, the starter was put on, the belts were already on, and the fan blades were on.

WAC: When was the transmission mated up to the engine?

CP: The motor would go down through the first floor. The transmission department was on the first floor. It was mated up there, and then it would go back up. When it came back up the motor and transmission were together. It never went back onto the motor bridge. It simply went back up and across a screen grating to get over across an aisle, and then it would go to the north and it would swing and come right in beside the production line.

That’s where the frames were. It would ride above the worker’s heads in a screened in cage until the next time it came back down, it came right down beside the frame it was supposed to go into. It hung on a balancing rod, and a guy with a hand operated hoist that had like a two and a half inch solid steel L. He’d walk up there pick that motor right up off the line go over and set it down right into the frame.

One guy on each side would put motor mount bolts in. Another guy behind them was putting transmission bolts in. Within fifteen seconds that motor and transmission was bolted in. The guy would remove his hoist, and one of the guys that had just put in a motor mount bolt would unhook this bracket off and just throw it into a huge steel tub to be taken back to Plant 9 to be used over again. The brackets were hooked to the eyelet on the passenger’s side of the front, a flat wedge that went in behind one of the bolts that held the timing cover on, and the other eyelet was on the driver’s side of the block. It was a hole on the back of the block.

That hoisting bracket set across that motor and balanced it with the transmission on the back. The rod that came across there, there was five notches in it. The guy that put the hoist in, he would look, if he had a turbo 400 big car unit which had a long tail, he would put it in like the fourth notch back to get the motor to hang level on his hoist. If it had a four-speed, he’d go maybe to the second notch. He knew which notch to go into to hang it right. It was done so fast and proficient it was unbelievable.

WAC: You started working at the plant in late 1963. Did you ever see any Super Duty cars in the plant?

CP: I never seen any of them assembled. I seen the motors sitting in the plants. I heard a story about some “Pike’s Peak” cars. Supposed to have been a dozen red Catalinas with Super Dutys. I’ve seen red cars. I remember seeing red cars out by the Quonset hut. I have no idea if they was “Pike’s Peak” cars, if they was Super Duty or what they were.

I didn’t go pick up the hoods and look under them. But I did see Super Duty engines. The engineering building had one. And at one time they had a tri-power GTO motor that was painted black. It wasn’t Pontiac blue, it was black. It had chrome exhaust manifolds on it. It had a chrome intake manifold. It had chrome tappet covers, and it was painted black. It was really pretty. It sat on an engine stand in the engineering building. It was a show motor.

They had Super Duty motors in there. At the time, I don’t know if they were what they called “bathtub” manifolds or not, but they were aluminum, dual quads, huge strange looking’ things that we didn’t see on the production lines. We didn’t know what they were. We didn’t know if they were going to be in production on next year’s model, last year’s model or what. Unfortunately they had already been through their heyday and weren’t going to be produced any more.

I don’t have any idea where them motors went to. I know a young lad who works in the old Plant 8, which right now is a warehouse; just a storage place is all it is. I know that they scrapped a rack of Ram Air V motors, which went to Sam Allen’s junkyard in Pontiac. General Motors demands that he crushes, or melts or destroys them. And they watch to make sure that that’s done. He said that he knew that there was a rack, which is five, that went out there. These were complete, assembled motors that had been stored there for years, and they were scrapped. I don’t know why they would do that, but they do. These were completely assembled motors. They were good, but they were scrap as far as the company was concerned.

WAC: How many items “walked” out of the assembly plant?

CP: Truthful figure, who knows. Tremendous amounts. Everybody that I ever knew at Pontiac Motors took what they wanted, I guess. Everybody did it. Things like GTO emblems, you took a few. Things like 421 emblems, you took a few. It was the thing to do.

WAC: What’s the largest single item you ever saw liberated from the plant?

CP: A tri-power.

WAC: A complete tri-power set-up?!

CP: No, a complete 421 HO tri-power motor! A complete motor. Fans, belts, exhaust manifolds, transmission, air conditioning pump. That was an HO motor and it was complete. I think that was a ’65 or ’66 motor that was supposed to go into a Grand Prix. That particular engine had an air conditioning unit on it. I would imagine it got thrown in the junk. The morning after that happened, I remember they didn’t have a motor for that car, and it was built without one. They must have put a motor into it at a later date.

WAC: What about pieces that didn’t fit quite right? Maybe something like a fender.

CP: I don’t remember them taking a fender back off just because it didn’t fit right. If it was put on and the paint color didn’t match the car – they might have had a red car and a white fender – they would build that car and somebody would change that out later on. They would go ahead and build that car no matter what. If there was a screw hole maybe that didn’t get stamped out, it just didn’t get a screw through it.

Chances are that went right on out the factory to the dealer without a screw in it. Chances are that car went on down the road a hundred thousand miles without one screw in the fender. I know a lot of bolts I put in were stripped, and you forced them in with the air wrenches. There wasn’t a problem. You didn’t anticipate somebody takin’ ’em out. You just went ahead and drove ’em in. If you could put ’em in and tighten ’em up, why, that was just part of the program.

WAC: How did the inspectors mark problems? Did they have O.K. stamps, chalk sticks?

CP: Inspectors carried colored pencils or chalk, and if they seen a bolt that was stripped or wasn’t in all the way, they’d just chalk around it. Then you had your repairman at the end of each area. He might have twenty different places he’d be lookin’ at, and if he didn’t see any chalk, he didn’t have to fix anything. If there was chalk on something, he’d back that bolt out, run a tap down into it, and put a new bolt in. He would fix whatever he could.

Say a bolt was broken off, it went in crooked, or the head was twisted off, and there was chalk on it, obviously he can’t fix that there. He doesn’t have the time. He only does a quick fix. The car would go right on through production and it would go to final repair in the back end. After every station there was an inspector’s ticket that would ride with that car. The inspector had a little hole-punch. It would have maybe an “R” on it, and that stood for that particular inspector. They knew who did that. He would punch that ticket and leave it, say, behind the power steering pump.

When that got down to final repair they’d look under the hood at that line building ticket, they’d see that “R” punched there. Then they’d look at that power steering pump and say what’s wrong here. Maybe they’d get on the phone and call the inspector and say, “I’ve got such and such a car here, do you remember what the problem was?” Usually they could see a bolt twisted off or something. They would tear this down, take it out with pliers, drill it, tap it – whatever they had to do. If they had to change the whole head on the car, they probably would just pop the engine out and put another motor into it. But then that engine would get repaired and used over again. If that called for a Catalina two-barrel automatic code engine, they just got the next available Catalina two-barrel automatic code engine out of their bank and put it into there.

Topics covered in part five:

Engine Unit Numbers

V.I.N. stampings

The spray booth

Electrical check

Plant Accidents

Made in Pontiac PT4 Image 1

Tempest Custom begins a lateral transfer (towards the camera) to Line Two on the main floor.

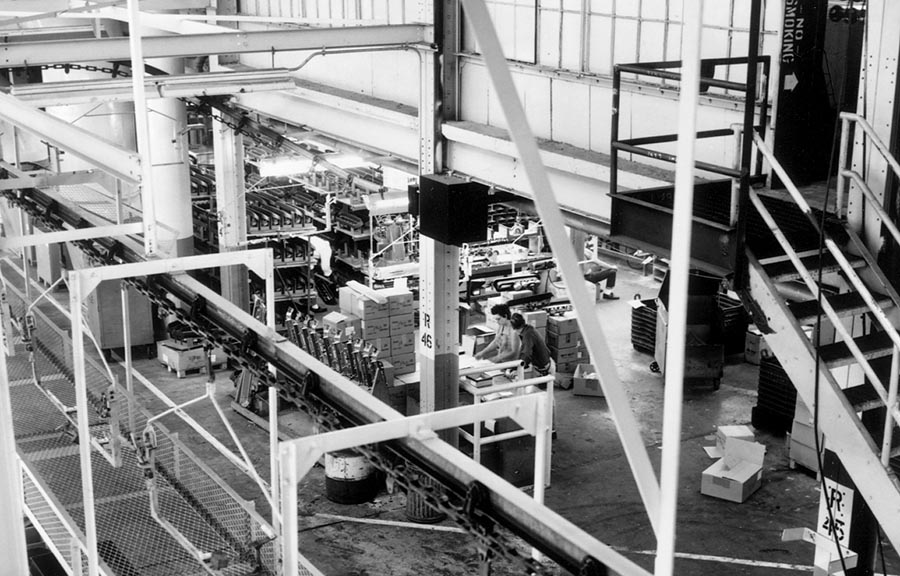

Made in Pontiac PT4 Image2

Here’s the beginning of Line Two. Cars travel backwards down this line. See Part 1 of this story for Main Floor schematic.

Made in Pontiac PT4 Image4

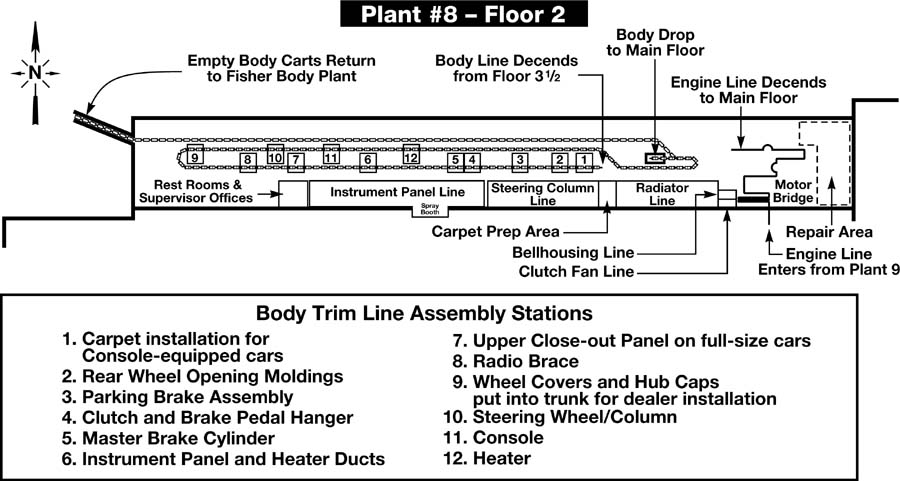

Instrument panel line on Floor Two. Consoles can be seen sitting in boxes. Instrument panel pads are in background.