Reprint with permission only

(For more information about the Buick Nailhead, visit www.nailheadbuick.com).

Like the Small Block Chevy, the Rocket 88 Olds, the Ford Flathead and the Chrysler Hemi, the Buick Nailhead engine is one of those that has the immortal smell of history all over it. Yet, unlike its more familiar brothers, cousins and even competitors, the Nailhead has an aura of mystery about it as well.

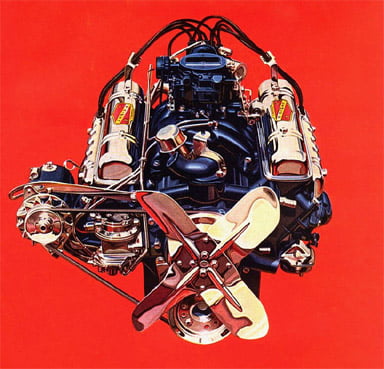

The Nailhead had a big-bore, short-stroke design that offered tremendous torque, spread out over a wide RPM range. Introduced in 1953, the overhead valve Buick design incorporated vertical valves (the small size of which gave rise to its somewhat uncomplimentary nickname of “Nailhead”) and a pent-roof combustion chamber. With its small valves and tight intake and exhaust ports, Buick used a very interesting camshaft as its stock offering, with higher lift and longer duration. The distributors were in the rear and the starters were on the driver’s side, unlike later Buick engines.

Built from 1953 through 1966, the Nailhead family included a variety of displacements including 264, 322, 364, 401, and 425 cu. in. variations. There were other size Buick engines produced as well that resembled the Nailheads (such as the 215 and 300 V8s), but they had no parts interchangeability with the Nailhead and instead are actually more closely related to the V6 and later Buick V8.

To clarify the history of these popular – yet often misunderstood– engines, I spoke with one of the true Nailhead experts in the country. Russell Martin, owner of Centerville Auto Repair in Grass Valley, CA, says “The reason few people know much about these engines is because there is so much to know. I have been amazed by the many changes made during the time the Nailhead was used from 1953-1966.”

The Nailhead was campaigned perhaps most famously by “TV” Tommy Ivo, who raced a twin-Nailhead (placed side-by-side) dragster as well as a radical four-engine, four-wheel drive dragster named “The Showboat.” So what was it about the Nailhead that makes understanding it so difficult?

“For years I heard guys ask what is so good about a Nailhead: ‘It has those small ports and valves!’” says Martin. “But they always ran better than they should. After doing a lot of research, here’s what I found: The less timing advance needed in an engine means it has a good combustion camber design; the Nailhead has the least timing advance (30 degrees) that I know of and the spark plug is right in the middle of the chamber for a short flame travel.

“The blocks have a tall deck height for a good rod stroke ratio (the taller block allows for a longer rod). The short stroke lets the engine spin quicker than a longer stroke engine. Smokey Yunick tried to get Chevy to correct this on the SB for years because its deck is way too short to use long enough rods for getting the most power,” Martin explains.

Other features pointed out by Martin: the small bearing sizes mean the bearings run cooler and need less oil. Every Nailhead, not just the high performance models, had forged rods and cranks. Rocker arm shafts are much stronger than studs with rockers on them. The whole valve train is very light so softer valve springs can be used for less engine wear and quicker revs.

The small exhaust valve heads don’t have as much pressure against them when they are being opened, meaning less pressure against them when they are being opened. Cracks are rare in a Nailhead cylinder head,” he says. “And they rarely leak oil because of the way the valve covers are designed.” The ports are smaller than most HP engines but designed with high velocity.

Of course, great design does not always mean simple – and in the Nailhead’s case that’s a fact you’ll have to come to grips with. First off, the Nailhead is more correctly labeled a THEM than an IT. According the Marin, the sheer number of variations can be staggering.

Different Blocks

“The reason few know much about these engines is because there is so much to know, I have been amazed by the many changes made during the Nailhead’s existence, ”Martin says. “The 1953 322 is a separate motor, with a special block, heads and pistons, etc., but the 1954-’55 and ’56 engines also have many differences, both with the 322 but also with the 1954-’55 264 engine as well. The 322 was also re-designed and used in large GMC and Chevy trucks from 1956-1959 – this version of the engine was called the Torque Master.”

He continues: “There were three (plus high and low compression models) 364 engines made from 1957-1961, with 3 different blocks, different con rods, heads and timing cover, rocker arms, and even starters! Buick made four different 401 engines, three of which have different blocks. Plus, there were two different 425s.”

The important thing an engine builder looking at this powerplant should do is find the correct year before starting the rebuild. “Certain engines cannot be used in some Buick cars because of bell housing, engine mount, block, oil pan and crankshaft changes,” Martin explains. “Plus, since all Nailhead engines were externally balanced, mixing dampers and flywheels with some models is not going to work.”

Getting your balance with the Buick is critical. “Because all Nailheads are externally balanced, the flywheel/flex plate must be installed with the index holes lined up,” Martin explains. “They can bolt on six different ways but only one way will be vibration-free! The 1957-’66 Engines MUST have their dampers tightened to 225 lbs ft. or the crank and damper will be damaged. They are a light press fit so the bolt must be this tight.”

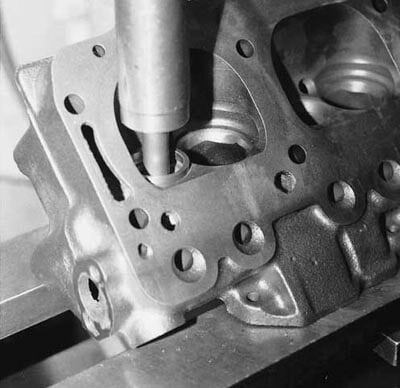

Cylinder Heads

Nailhead cylinder heads are very sensitive, explains Martin, who suggests allowing only experts in the engine to port your heads – you can actually lose horsepower if the job is done incorrectly, he explains. The best Nailhead porter I know is Mike Lewis of Pro-Tech, out of Fresno, CA,” Martin says. “He has spent months perfecting the technique of porting Nailheads and can improve flow by 25 percent.”

While rodders often turn their noses up at the word “stock,” Martin points out that the stock Buick cam is hotter than the smallest Isky cam and with stiffer springs will rev to 5500 rpm. “If you want a bigger cam make sure it has at least 214 degrees duration at .050˝ or you are just wasting money on a HP cam”, he says.

“If you are using an aftermarket performance cam, ALWAYS degree in the cam,” Martin cautions. “This is very important – do not skip this part of the build. I have timing sets with 9 positions so I can correct any cam that is off. When not using adjustable rockers we always use adjustable push rods, put the adjust nuts down in the valley for easy adjustments, with a hydraulic cam you are only going to do this once.”

Additionally, valve springs are critical. “I have the correct size high performance valve springs in several spring pressures including a special spring for stock cams,” says Martin. “The spring pockets in the heads must NEVER be made deeper or enlarged, because doing so will put the spring into the push rod hole!”

The early 264-322 heads (up to mid-1955) have a very small pushrod hole that should be enlarged if a larger cam is used, explains Martin. All 1959-1966 364, 401 and 425 heads have the same ports and valve size; the 1957-’58 heads are the same with smaller valves. However, he says the heads manufactured between ’53-’56 are different for every year. “Back in the day, hot rodders would swap the early round exhaust port heads for the ’57-’66 rectangular port heads for racing; but then custom pistons and intakes were needed. I had Mike Lewis flow a ’55 264/322 head for me and even with the smaller ’53-’56 ports and valves they were still only 10% less than the ’57-’66 heads!”

Understanding the Nailhead’s valve seat requirements is very important, warns Martin. “You should never install hardened seats. The coolant passages are too close to the seats, so you are likely to either cut into the coolant passage while cutting for the seat or the metal will crack while installing them! There are a handful of Nailhead guys who can do it, but guess what? You don’t need hard seats. These heads have a high nickel content along with small, lightweight valves and soft valve springs. I have rarely seen bad seats. And the ’54-’58 heads can just use larger valves from later engines as needed.”

Martin says valve guides require another caution. “Don’t use anything but cast iron guides unless you are using roller rockers,” he explains. “The stock short rocker arms eat up bronze guides in a short time.”

Valve seals were only used in 1966 and on the intake guides only. Martin says you can add them to all Nailheads but never install exhaust valve seals. “Very little oil is going to enter the exhaust guide and you need oil there so the exhaust valve stem does not run too dry.”

The newest style head gaskets aren’t necessarily appropriate for these engines, warns Martin. “Without the right gaskets, engines can leak oil front and rear of the gasket from the oil passages that feed oil to the rockers. The gaskets should have a raised circle around the oil passage hole but without it and the way modern gaskets are made from layers of material these tend to leak. I have tried sealers but now we use vintage style or factory steel gaskets with no problems.”

Building It

The process of building a Nailhead, Martin says, starts with a thorough cleaning and deburring of the block. “This makes the block stronger so cracks can’t start and makes it easier to install the cam bearing without cutting your fingers on the casting flash around the lifter bosses plus if a piece of casting flash breaks off later it can ruin your engine. These engine blocks rarely crack but if they do, the crack is usually hidden by the starter. Before buying any of these engines, remove the starter and look at the block closely in this area. There are ways of repairing this but none are cheap, another block is the best way to go.”

Martin next pulls the oil galley plugs and cleans the passages. “I use a dent puller to pull the first one so I can knock the others out with a long rod. We’ve had the correct oil galley plugs made; all that was available was 5/8˝ and that is .015˝ too large! I use two plugs on the galley hole behind the distributor –there is enough room without blocking oil passages unlike the 3 front plugs –and apply green thread locker on all of them.”

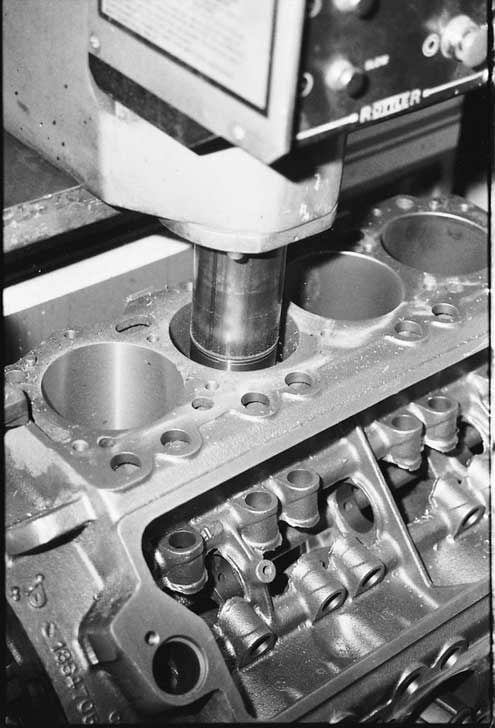

Next, the engine gets squared up by decking. “I bore and hone it with a honing plate. The honing plate, distorts the cylinders just like when the heads are torqued down so the cylinder will be perfectly round when the engine is together”, Martin says.

All clearances are kept as close to factory specs as possible. Martin says he prefers to use the factory Buick oil pumps, whenever possible to prevent binding of aftermarket units that can occur unless the mounting holes are opened up and the pump is moved around until it doesn’t bind. “There are rebuild kits available,” says Martin, “so I rebuild the factory ones and pack them with petroleum jelly.”

Martin says the next step is to have the assembly balanced and then assemble it with oil (or assembly lube), NOT grease. “Grease can plug oil galleys and ruin your fresh Nailhead.”

He continues: “Before installing the crank we install the rubber rear main seal. We have had some problems with these seals, not because the seal is bad but because some blocks have shallower seal grooves machined in them than others. This causes seal distortion when the cap is torqued down. If the seal lip looks distorted, grind the seal ends a small amount where they butt and re-check the seal.”

The next step is to install the bearings and crank can be installed. The crank should spin smoothly by hand. “To date I have had only one Nailhead that needed line boring of the main bores,” says Martin. “Line honing is not an option with these blocks, because you can’t control how the material is removed. Boring lets the machinist control where the metal is removed so a minimum metal is removed from the block – most is taken from the main caps. If the crank is brought closer to the cam you will get a loose timing chain and you don’t want that, there are no oversized sprockets available to tighten the chain back up.”

When installing the pistons, always oil the rings and space the end gaps on the top two rings.

Martin recommends that engine builders stake the front oil galley plugs. “Tapping for screw-in plugs is not a good choice for these engines,” he explains. “There is not enough room, you can block off oil passage holes and/or cam sprocket will not clear them. I have never even heard of a cup plug falling out of one of these engines.

Martin explains how on a recent Nailhead build, he used a rear sump pan along with a custom oil pump pickup with a larger tube. “Using this pan gave me some free horsepower – you don’t want the crank and rods being slowed down hitting that oil. The 1965-’66 GS version already has a lower level from the factory because Buick used a ’57-’60 6-quart pan with only 5 quarts of oil in it.”

The hardest part of a Nailhead rebuild, Martin explains, is installing the cam bearings so he leaves the hard work to someone else. “I have the machine shop install mine. Always have an old cam for them to use to fit the bearing, and after you get it home, make sure they are installed with the oiling holes lined up and MAKE SURE THE FRONT BEARING IS IN CORRECTLY. This is a common mistake and is a real pain to fix after the engine is in the car. If it goes in wrong you won’t get oil to both lifter galleys. Another common mistake to watch out for is leaving out the plugs in the oil galley behind the distributor.”

Next, all the threaded holes should be tapped and the whole thing should be scrubbed with soap and water. “Get all the water off quickly and oil the insides,” says Martin. “Get a paper towel with ATF and clean the grit out of the cylinders. Keep doing it until they are clean.”

When you ready to assemble, Martin cleans the backs of the bearing and where they fit with lacquer thinner. “That allows the heat to flow easier from the bearing into the rod or block, keeping the bearings cooler,” he explains. “The rest of the short block build process is by the book.”

401 -425 Camshaft Specifications

| 401 | 59-61 | 62-63 | 53 Late 64 | 65-66 | |||

| 425 | 63 | 63 Late 64 | 65 | ||||

| 425 - 24331 | 64 | 65-66 | |||||

| Cam Part No. | 1185918 | 1351515 | 1359442 | 1358100 | 1362242 | 1368091 | 1368090 |

| # on Shank | 1174480 | 1174480 | 1174480 | 1174480 | 1362241 | 1362241 | 1362241 |

| Machined Groove in Shank | .060" | None | None | .060" | .060" | .120" | None |

| Timing Advance of #1 Exhaust Lobe Ahead of Sprocket Keyway | 2°30' | 50 | 50 | 0°30' | 0°30' | 0°30' | 5° |

| Exhaust Duration ° | 299 | 302295 | 299 | 299 | 299 | 299 | 295 |

| Exhaust Lift In | .441 | .439 | .431 | .441 | .441 | .441 | .431 |

| Intake Duration ° | 290 | 295 | 295 | 290 | 290 | 290 | 295 |

| Intake Lift In | .439 | .439 | .431 | .439 | .439 | .439 | .431 |

| Spacing ° | 109 | 114 | 109 | 109 | 109 | 109 | 114 |

| Exhaust Open BBC° | 75 | 76 | 76 | 71 | 71 | 71 | 76 |

| Exhaust Close ATC° | 44 | 46 | 39 | 48 | 48 | 48 | 39 |

| Intake Open BTC° | 33 | 28 | 28 | 29 | 29 | 29 | 28 |

| Intake Close ABC° | 77 | 87 | 87 | 81 | 81 | 81 | 87 |

| Overlap° | 77 | 74 | |||||

| Dennis M Manner | |||||||

| Manager Engine Design / Buick-Olds Cadillac Flint | |||||||