Why Did Chrysler Dump the Original Hemi?

By Society Staff – reprint with permission only

Few of us were around (or old enough to recall) the big news for 1959 at Chrysler – the Hemi was gone! Though still available in the Imperial, the big bad 392 was history, replaced by the “RB” 413. Know this, Chrysler took a lot of heat from the performance community when they dropped the Hemi in favor of the wedge big block.

But the real question was why? First, we have to go back and understand the times. Wedge engines were sophisticated and combustion chamber design was far enough along that solid HP was not a problem in the wedge engine camp. Buick’s rather tame 401 made a solid 325 HP, Cadillac’s Eldorado had 390 cubes and 345 HP, Lincoln showed up with 375 ponies, and a Pontiac 389 punched out made 345, and many of these engines were slow turning high torque power plants.

A big answer was in what the Hemi was actually called in the day – “double rocker”. This meant the need to have two rocker shafts per head to activate the valves rather than the one used by the wedge; the rationale becomes clearer. Adding in the size and weight of the Hemi head also added to the recognition that perhaps there was little need for such a complex engine.

If you know your Chrysler history, you will know that a “Polyspherical” cylinder head was offered from 1955 to 1958 in Windsor models. This was a single rocker head that bolted directly to the Hemi block (in fact, it used the same intake manifold). The 1958 “Spitfire”, as it was known, at 354 CID, made more HP than the 1956 Hemi of the same displacement! That taught Chrysler that the Hemi was unneeded for regular production.

Another limitation was the cubic inch limitation of the 331-392 block as it would have needed a complete redesign to go to more cubic inches, the handwriting was on the wall. With that information, and when one added in the additional cost of manufacture of a 392 Hemi, the smart move was to go wedge when coming up with a lighter, more modern design.

Further, Chrysler recognized that they really had too many different engines in the Corporation’s lineup. In 1956-57 they had 2 Chrysler engines (the Hemi and the Poly), three DeSoto mills, two Dodge engines, and three Plymouth V8s. All the separate supply chain issues, the training and separate service costs – and most of all – the huge R&D costs to improve and redesign these V8s were just insane. And since Chrysler was number 3 in the big three – reducing costs version production numbers was a priority.

When Chrysler designed the new wedge “B” and the high deck “RB” blocks, they took into consideration the Country’s appetite for large displacement engines and made sure that the RB could go all the way out to 500 cubic inches if necessary, and that the B could go to 400.

The new B and RB power plant was also designed so that they could be delivered in engine sizes from 350 CID to 440 with no extra costs, and that they could use the same cylinder heads, associated parts, and machining – making it an engine that could be shared across the entire Corporation’s line. The reduction in manufacturing costs, and the ability to provide parts and pieces to all brands, virtually wiped out their huge supply-chain cost and delivery issues in one stroke.

Chrysler knew its cars were sought by many for their performance, so there was the Hemi mystic and lure. From 1954 on, there was a Hemi in each brand except the lowly Plymouth. Surprisingly, however, it was Plymouth that proved to Chrysler that the wedge could make it when paired up against the Hemi.

Plymouth started the ball rolling performance-wise in 1956 with their 303 cube Fury – making 240 HP when the mighty 2 4-barrel Chevy and Ford had 225. By ’57 the 318 Commando made 290 and in 1958 it pumped out 305 ponies from 350 cubes.

This last iteration, the 350, was the first of many “B” series wedges to come. This block would soon become the “RB” 413-426-440 (called such because it was a raised block deck B engine). The “B” block would spawn engines from 361 through 400 cubes and become the famous 383 that powered the Road Runner. In “Long Ram” format, the 383 would be modestly rated 330 HP. The 361 B engine powered a 1960 Plymouth to 15.6 @ 90 mph. When Dodge added the 383 B to their lineup they were able to pull a 14.93 @ 91.

So when the same high-performance pieces were added to the RB, some serious HP occurred. Rating-wise the 413 in the ’59 Chrysler made 380 HP and 450 ft. lbs. of torque, the exact numbers delivered by the Hemi the year before. But the proof was in the pudding. The ’58 300 Hemi produced a 16.10 quarter mile @ 87 mph, and a wedge engine1960 300 F ran 16.0 @ 90 mph. When the car got lighter in ’62, Hot Rod got a 14.73 @ 98.

Considering the cost issues, the availability across the entire Corporation’s line, and weight savings, there was just no justification for the Hemi. We know the Hemi returned on the “RB” block, but if you read carefully, you will see the justification wasn’t for those awesome drag races and street machines; it was to win NASCAR super speedway races.

Frankly, if Chrysler hadn’t been so obsessed with the NASCAR venue, we likely would never see the Series 2 Hemi – ever.

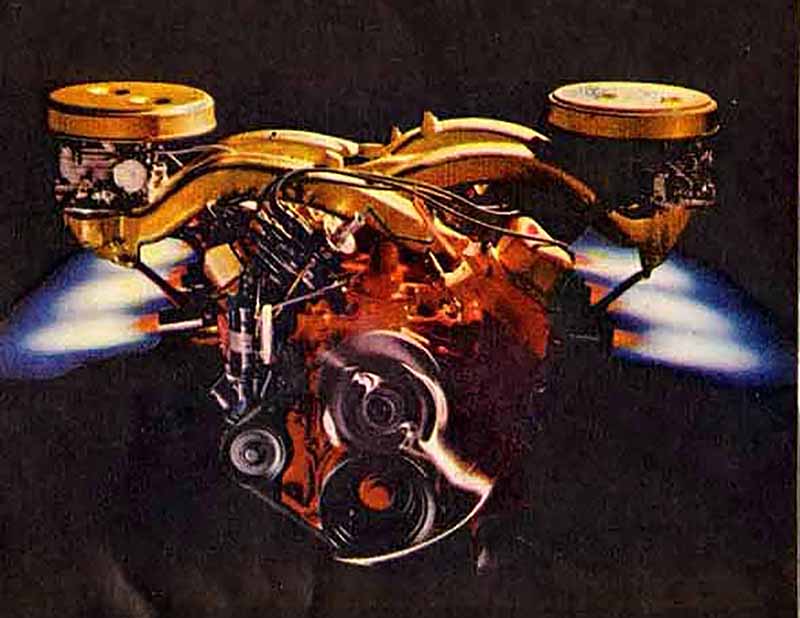

Chrysler Hemi Image 1

The 1957 Chrysler 300 was the high water mark for the Series 1 Hemi. The picture inset shows the “double rocker” and its complexity

Chrysler Hemi Image 2

The “RB” 413 was delivered in Chrysler 300s in either long ram, short ram or traditional twin 4-barrel configuration

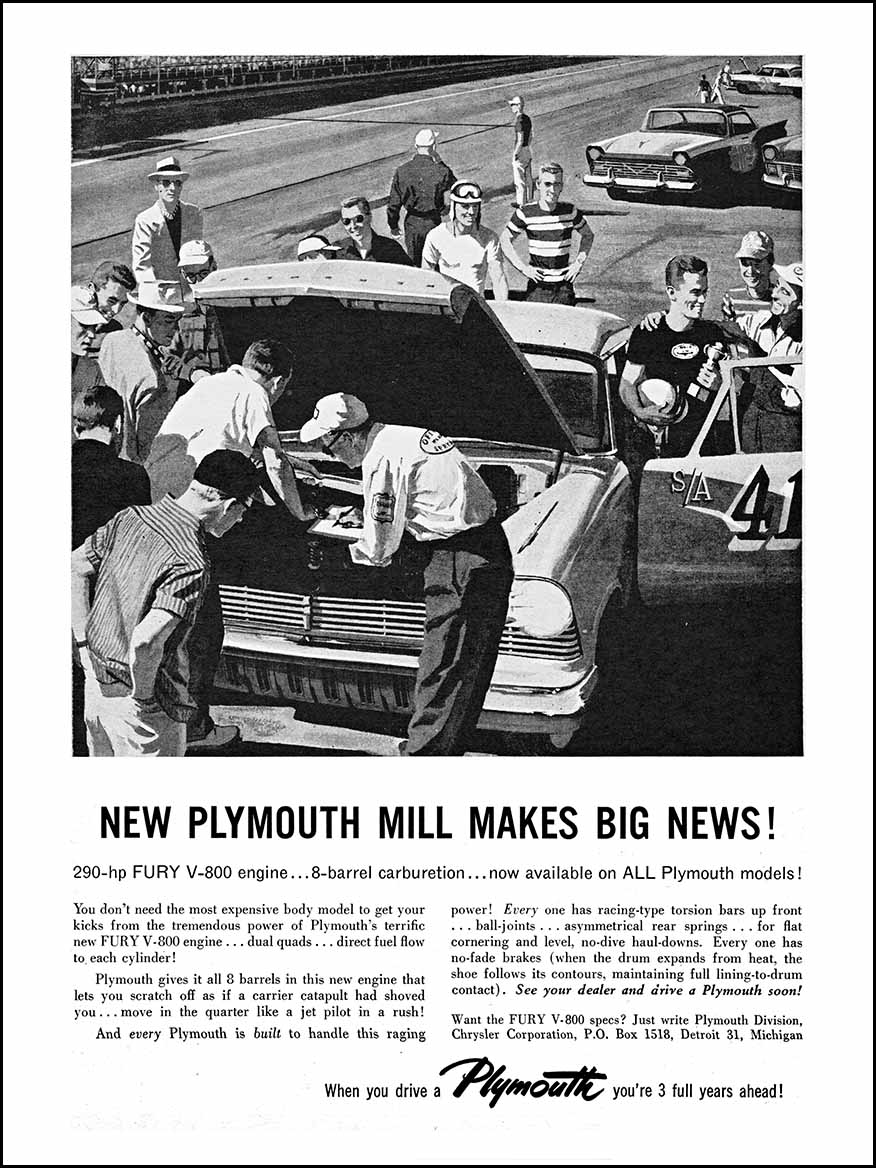

Chrysler Hemi Image 3

The “B” engine was no slouch. Here it is in 1959 with its long ram manifold working full song.

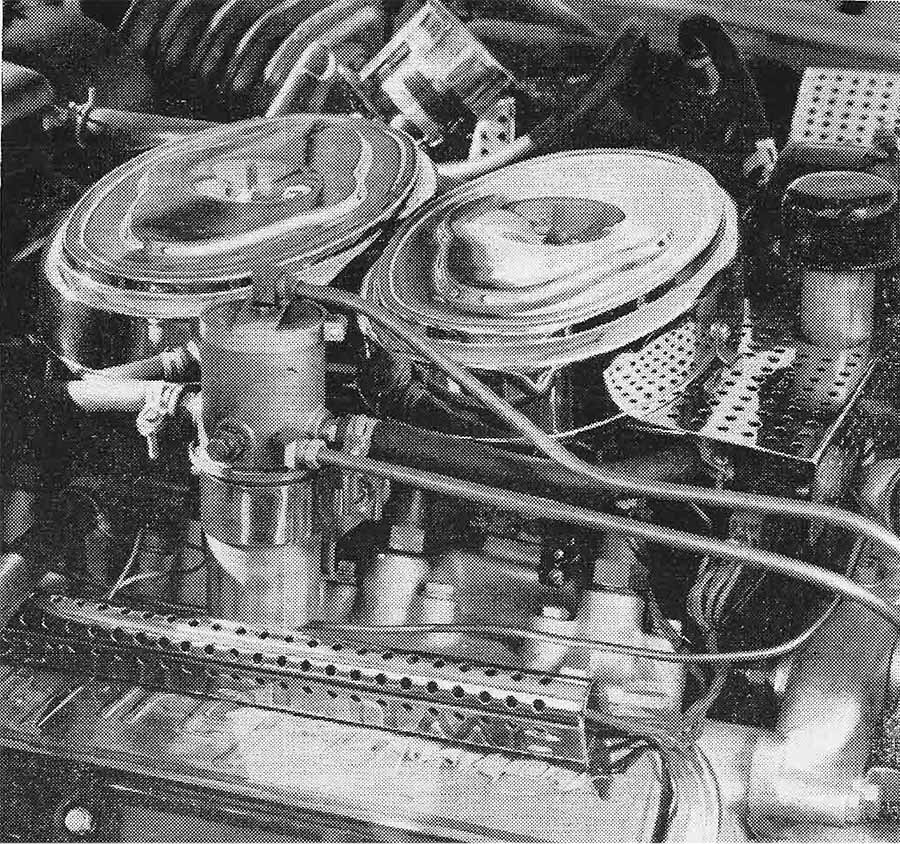

Chrysler Hemi Image 4

Chrysler experimented with fuel injection in 1958 300 in an attempt to get more “streetable” HP from the 392. It did not go well, reinforcing the move to the “RB”