Jim Wangers – Promoting Performance

by Eric White,

Reprint with Society permission only

Introduction-

Jim Wangers will be the first to admit that he has been, by design or by fate, in the right place at the right time on many occasions during his long and eventful marketing career. His influence on the incubation, emergence, and maturation of the post-Korean War American performance automotive marketplace can be credited in no small part with the colorful, high-energy exuberance of the Supercar/Musclecar of the 1960s. Without his unique blend of enduring fascination, innate knowledge, and prescient direction, the history of the sizzling supercar ’60s, vinyl-striped & spoilered ’70s, reemergent ’80s, and computer-enhanced ’90s would look very different today. During this multi-part interview, Mr. Wangers will guide us behind the scenes of this volatile and exciting period of U.S. automotive history. James Wangersheim was born on June 26, 1926, placing him in the later part of the generation tasked with fighting WWII. He grew up on Chicago’s north-side, and from the time he was able to discern what an automobile was, Jim has been a true car guy. As a child, he clipped car ads out of magazines, and decorated his bedroom with these automotive images of mechanized motivation. Following graduation with the class of ’42 from Senn High School, a year of study at the University of Illinois was completed before Uncle Sam called him to duty. From 1944 through 1946, Jim’s wartime service in the Navy found him aboard the Essex-class aircraft carrier the U.S.S. Bunker Hill as a Radioman 3C. Shipboard, he wrote to all the carmakers for his own copies of their latest sales brochures. The highly decorated ship and crew found themselves knocked out of the war by Japanese kamikaze attacks while supporting the invasion of Okinawa in April of 1945. Following the end of the war the Bunker Hill was part of the armada employed to return servicemen home from the Pacific Theater. Upon discharge from the Navy in ’46, it was back to school, this time at the Illinois Institute of Technology. Here Jim worked on the student newspaper. He eventually earned a degree in English. In 1949, Jim took a job at the Chicago Daily News, followed by a position at Chicago-based Esquire Magazine. It was while working at Esquire that Jim became acquainted with fellow worker, future magazine publisher, and entrepreneurial playboy/philosopher, Hugh M. Hefner. At one point, Hefner asked Jim to join him in a new publishing venture. Not liking the odds of success in helping to start up a new men’s magazine in the prudish environment of the early 1950’s, Jim instead remained with Esquire and accepted a transfer that moved him to New York City. Soon the opportunity to become involved with the auto industry presented itself in the form of a job offer from the NYC-based advertising agency of W.H. Weintraub and Co. Jim’s carefully crafted knowledge of automobiles served him well in this position. In 1951, Jim made the fateful move to Detroit in order to work in the Weintraub agency’s Kaiser-Frazer account office. He was employed by Weintraub until early 1954 when K-F closed its doors and the account was terminated. Greener grass was spotted at the Campbell-Ewald advertising agency, where GM’s Chevrolet Division ad account was handled. His career in the auto industry was by now well established. It was during this time period that Jim decided to shorten his last name to Wangers. Here is where we pick up the interview conducted on September 4, 1994 in Long Beach, CA.

Digging in with Chevrolet: Let’s go racing –

Wild About Cars: What were your responsibilities at Campbell-Ewald?

Jim Wangers: I went to Campbell-Ewald, in Detroit, in late spring of ’54 to work on the tail end of the announcement of the 1955 Chevy. I went to the experience down at Daytona in February of 1955-the speed week experience. I came back and got Chevrolet interested and involved in that racing program. That went all through the summer of ’55. Then in August of ’55 I got involved in the Pikes Peak program. That whole program came off the ground during the ’56 model year. In December of 1955, I left Campbell-Ewald and went to Chrysler, working in their racing department merchandising their racing victories and working with their creative people at the ad agencies.

Society: What was your title there?

JW: I was marketing manager for racing and performance motorsports. Then I left in March of 1956 to become assistant sales promotion manager of Dodge. In July of 1956 I was promoted to sales promotion manager of Plymouth. I stayed there through ’56, ’57, then in March of ’58 I was summoned by the McManus, John & Adams agency to join them on their Pontiac ad account. I came in as an assistant account executive on the Pontiac account. Pontiac goes drag racing- Society: How did you get involved in the drag racing end of the hobby? JW: Well, I was always interested in drag racing. From the very beginning, as a racing enthusiast, even from my early days going to Daytona Speed Week as a spectator, the one thing that always intrigued me, more really than track racing or sports car racing, was really the growth of drag racing. It was only at the tail end of the 1950’s and the early ’60’s that “stock car” activity in drag racing really came into its own. I like to think that I was right at the leading edge of all of that, within the industry, to help promote building cars for that kind of performance activity. That really is what happened all during that marvelous period of the ’60’s. We [Pontiac], in fact, were building cars for their performance on the drag strips. It was important to us that these cars actually were good performers. That’s really, in a sense, what lead up to that horsepower race, even though it was more dramatically personified, maybe, in terms of the “race cars.” It was early in the 1960’s that some of the motorsports activity from the manufacturers, the racing activity, took off as a very special genre. They were building aluminum parts and fiberglass parts, and everybody got into a competitive motorsports and racing effort which General Motors finally stepped up to in the late ’62 model year and made the decision that they were gonna not get caught in that trap. That, however, did not stop them from going right ahead and building more excitement and more performance into their production cars. That’s what the GTO started. We found ourselves in a very seriously competitive horsepower race, but with the production car, not necessarily with these limited-production, special one-of-a-kind race cars. That is one of the things that I got involved in very, very early in my participation with Pontiac.

Over-the-counter performance-

I was very, very much aware that Pontiac, during the period when they were actively involved in racing-’59, ’60, ’61, were making an awful lot of parts available to the limited production specialty cars. These cars were falling into the hands of the serious racers or dealers even that were interested in getting involved in not only just racing, but you know, drag racing. What bothered me very much was that the biggest percentage of the Pontiac retail organization didn’t know of the availability of a lot of these parts. I’m talking about things like: special axle ratios and camshafts, those special exhaust manifolds, a lot of that Super Duty equipment that became available in the ’60’s, transmissions, Hurst shifters which were originally put on in the aftermarket across the parts counter, suspension options, some special springs and shocks that were available.

So what I put together as a representative of McManus, John & Adams was a program that would involve a kind of a traveling seminar, really a sales training program that, quite honestly, was a little bit ahead of its time. What I wanted to do was go out into the zone offices with a small group of highly trained specialists from the factory who would then set up sort of a seminar type discussion in each one of the Pontiac zone offices.

In those days there were twenty-seven of them. We’d invite dealers from each one of these zones, during a two-week or a three-week period, depending on the size of the zone in which we were holding the training session; in effect, holding school in those zone offices. The dealer would send a representative from their sales department, from their service department, and from their parts department. The attendees would learn how to sell the new car from a performance point of view with a lot of this very special limited production equipment that could be run if the car were ordered properly from the factory. And I’m talking about such sophisticated things, as even, as I mentioned previously, axle ratios. You could order cars, for example, without all of the insulation in those days, without the dumb-dumb so to speak, that served as sound-deadener material. You could order them without that deadener if you were interested in building a truly performance-oriented car, and didn’t want that extra weight-if you knew how to do it. With this whole seminar, the goal was to teach the sales people how to sell these new cars. Then teach the service department how to service them, how to sell some performance parts, and at the same time teach the parts departments how to stock the right number of these parts so that it would be a totally successful effort, so to speak.

I presented this program to then the general manager of the division, Bunkie Knudsen, and he called in his sales manager, a chap by the name of Frank Bridge. Frank was a kind of a tough, two-fisted, old-school sales manager who was pretty successful and got the job done, but he was not really what you would call a modern thinking guy. His whole m.o. in terms of getting to the dealers and getting cars out there was to get the dealers drunk, take them out one-on-one, and kinda really romance and entertain them, then pour a bunch of cars down their throat and place a bunch of programs on their table. It worked back in those days. So I made this proposal to both Mr. Knudsen and Mr. Bridge, and Frank took a very cantankerous attitude about it. He said, “Aww, I’m having enough trouble just gettin’ my cars sold to these guys. We’ve got so much going on here with different car lines, I don’t really want to get involved in that.”. For Bunkie Knudsen, as general manager this was a subject that was very close to his heart.

Shortly after the meeting in which I kind of struck out in being able to set up this traveling seminar training program, Mr. Knudsen contacted me and he says, “Look, I like your idea, but I can’t second guess my sales manager. So what I really would like you to do is go find a dealer, preferably in the Detroit area, who you might make a guinea pig out of; a guy who would like to get involved with a performance operation, who would like to show the rest of the dealers how this thing can be turned into a very realistic and a very serious business. He’d help us sell more of these exciting performance cars and at the same time stock the parts that they necessarily need, train the service people to be able to service these cars, put these parts on when they get to the point of delivery. See if you can’t find a guy who will show that this can be done and done very effectively.”. It didn’t take me very long to find that dealer, and that’s exactly how Royal Pontiac got started.

Royal Pontiac steps up –

Royal Pontiac was run by a guy by the name of “Ace” Wilson Jr. They were headquartered in Royal Oak, Michigan, which was relatively close to the Pontiac factory. He was smart enough to figure out that this could be a pretty good program for him. Of course he had the benefit of having some pretty good promotional people involved in it. I was going to kind of oversee it. One of the first things that I talked him into doing was to put a car in action on the local drag strip. In that capacity he did, in fact, get one of the early Super Duty cars.

We started out actually in 1959 with the pre-Super Duty package. It was what we called the “Isky” package. Pontiac offered an optional camshaft. It was an Iskandarian package that featured a conversion to a solid lifter valve train, some special gears and a couple of little different suspension items. We didn’t have any lightweight parts or anything.

When the Super Duty package came about in the spring, it premiered first in Daytona in 1960 on some of the NASCAR Winston Cup cars, or Grand National cars as they were called then. We also moved very quickly to get some of those parts into the hands of the drag racers. Of course Royal fielded one of these cars, and one of the deals I had made with Royal when I put that program together was that I would drive their car, which was really a labor of love.

I certainly enjoyed the track participation. In that particular market, as was the case in almost every market at the time, the dealer that had visual exposure at the local drag strip was gonna certainly get a head start on doing some business in the area of high performance, both in terms of cars as well as service and parts. We were quite successful in building a pretty good image for Royal Pontiac as early as mid 1959 and well into the 1960 model year. Of course on Labor Day 1960, which in those days that was really the only big national drag racing event that the NHRA had, that event was held right in Detroit. We were lucky enough to win that event with our Royal Pontiac, Hot Chief #1 as it was called. We had three cars that were actually in that race. We had Hot Chief #1, which I drove, which was a four-speed, 389, tri-power. Hot Chief #2 was an automatic Hydramatic transmission, what they called a Whirlaway Hydramatic-a four-speed without a torque converter. It was a planetary gear set. Then we also had our ’59 in that event. The ’59, because Pontiac had not released a four-speed manual floor shift-controlled transmission in ’59, had to run a three-speed, shifting on the column. This was a real problem for that car, even though it was a pretty capable and a pretty reliable and good performing car.

Society: Who were the other drivers of those cars?

JW: Some of the other guys who were part of the Royal Pontiac team. . A guy by the name of Dick Jesse who was the sales manager of the new-car end of the business drove the automatic and a chap by the name of Clarence Walters, who was part of our service operation. Frank Rediker, at that time, was our chief mechanic on the racing team. Clarence Walters was one the service guys there who was a pretty good chauffeur. He ended up driving that car. It finished high, but not in the top three.

Society: When did you start drag racing?

JW: Well seriously probably in the 1955-56 year when the tracks were beginning to be readily accessible, when I was working for Campbell-Ewald.

Society: Was that a part of your job?

JW: No. It was really very much a personal, kind of an after-work activity. I had my ’55 Chevy. My first ’55 Chevy was a reasonably good drag strip car. Then I had the ’56 Chevy for a while. I had a ’56 Dodge 500, which had a three-speed on the column also. I had that ’56 Dodge in ’57. I kept that car. Then in ’58, when I went to McManus, John & Adams, I ended up with a ’58 Bonneville. It was a tri-power automatic with one of those Whirlaway automatics, a four-speed without torque converter. That was a pretty good running car. These were my own cars and they were all pretty much paid for by myself. I didn’t do a whole lot of modifying. They were fourteen-second cars, which in those days were fairly representative. It wasn’t until the first ’59, and then of course the two ’60’s, that I got Royal involved, and we began to run the Royal cars and we got some of that very special equipment.

Society: Did you learn to race from any famous drivers of the day?

JW: Not really. I think that my best teacher of the time was my mechanic, Frank Rediker, who gave me a lot of good pointers about engine set-up and engine build-up. There were some pretty good guys that participated against us back in the nationals that year. Ronnie Sox had a Pontiac there. A guy by the name of Harold Ramsey was there with a ’57 Chevy. He had won the nationals the year before with his ’57 fuel injected Chevy. Arlen Vanke was there with a Pontiac that he drove out of Bill Knafel Pontiac in Akron. This was actually before Hayden Profitt and Don Nicholson got into stock car activity. The stock cars came into their own, as you might appreciate, during those early 1960’s years.

Mr. Top Stock Eliminator, 1960 –

Society: So you had a good race that day.

JW: 1960 was one of the better days that I’d spent at the drag strip. That was on Labor Day, September 3rd I believe it was, 1960. We call it, and laughingly have referred to it many times as, “Super Duty Monday,” because Pontiac with the Super Duty package won the Darlington 500 Winston Cup or Grand National stock car race. We won the Pikes Peak hill climb, which had become, by 1960, an annual event. They had moved it into a competitive type class event. Then we won the NHRA Top Stock Eliminator at the nationals. I was lucky enough to be part of that winning trio.

That was in a sense a nice turnaround for me because of my win. I’ll never forget. I came to work the next morning-the Detroit Free Press had covered the race pretty aggressively-and there was a pretty nice story in there about how this guy who writes copy for the ad agency goes out and makes his own news with the car and then writes the copy. Kind of a neat angle on the story. It was a fairly well placed story in the sports section. When I got into the office that morning my immediate supervisor, who was the account manager or the account supervisor, gave me a call and said, “Whatever you want, ask for it today, because today is your day.” He says, “The first thing that’s going to happen is you’re going to have lunch with Pete Estes,” Pete was general manager of the division; Knudsen had already left and gone to Chevrolet, “and his performance assistant, associate chief engineer, John DeLorean.” John had not yet moved up to the chief engineer of the division.

Meeting John DeLorean –

It was on that day that I really met Pete Estes and John DeLorean. I had already met Mr. Knudsen, Bunkie Knudsen, who was general manager when I had tried to put that program into work for him, but I had not met Pete Estes or John DeLorean. That began a very nice relationship, particularly with John DeLorean for me.

As he moved up in the Pontiac organization, I moved up in the McManus organization. In 1961, of course, he became chief engineer of the division, and that was a very nice opportunity. He moved me up in the hierarchy in McManus. In 1965, long after the GTO had become a significant entity, I had built a very nice rapport with John and his whole organization. I was out there in an official capacity as a member of the agency-contacting the marketing and sales people-but I had also built a beautiful relationship with just about all of the engineering people. I was fortunate enough, because of John’s support for me, to be included in a lot of product planning groups. I also had a lot of opportunity to work with the development level of the product, which is how I got involved in the initial thinking and initial planning on the GTO.

I will give John DeLorean much of the credit, not only for my success in the early days by opening the door for me to make the contributions and have the participation, but also for supporting me. He made it possible for me to work in areas where nobody from an ad agency had ever really been allowed to get involved in at that early a stage.

John became the general manager in 1965 when Mr. Estes was promoted to Chevrolet. In that capacity I moved up to, really, the number two man on the account. The number one man on the account was the president of the agency, a chap by the name of Ernie Jones, who was a delightful guy to work for. He totally understood the reality of our relationship, and appreciated the fact that I had built this personal involvement with Pontiac.

– END OF PART ONE –

Topics discussed in Part Two:

- Working with John Z. DeLorean.

- Promoting Pontiac.

- Setting up Royal Pontiac.

- Woodward Avenue.

- Leaving Pontiac.

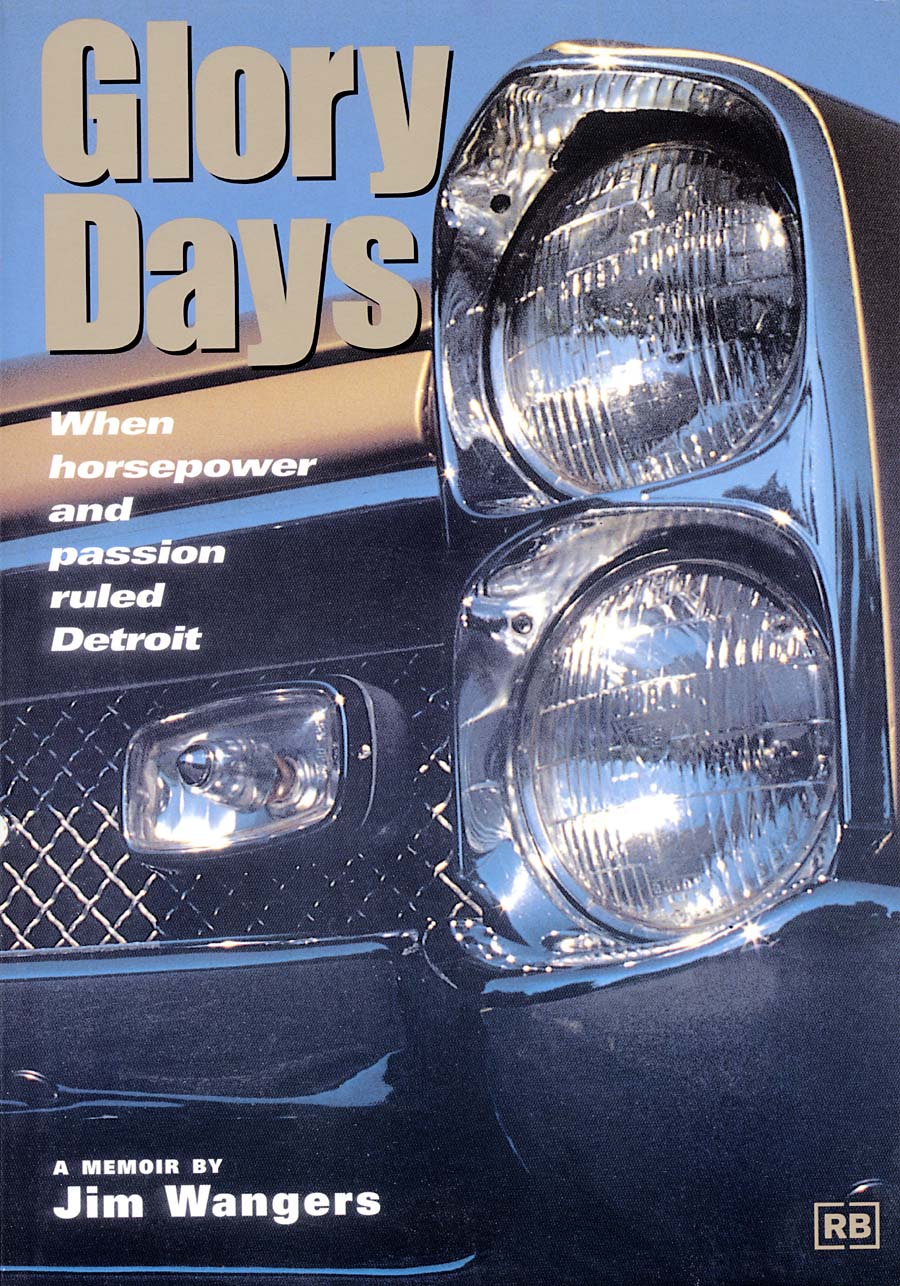

Jim Wangers Image 1

The honorary title “Godfather of the GTO” was bestowed upon Mr. Wangers by the enthusiast community in the 1990s.

Jim Wangers Image 2

Nicholas Senn Sr. High School, located in North Chicago, is where Jim earned his diploma in 1942.

Jim Wangers Image 3

Essex-class carrier, USS Bunker Hill (CV-17) served as part of the post-war armada ferrying solders back to the U.S. from the Pacific Theater of War.

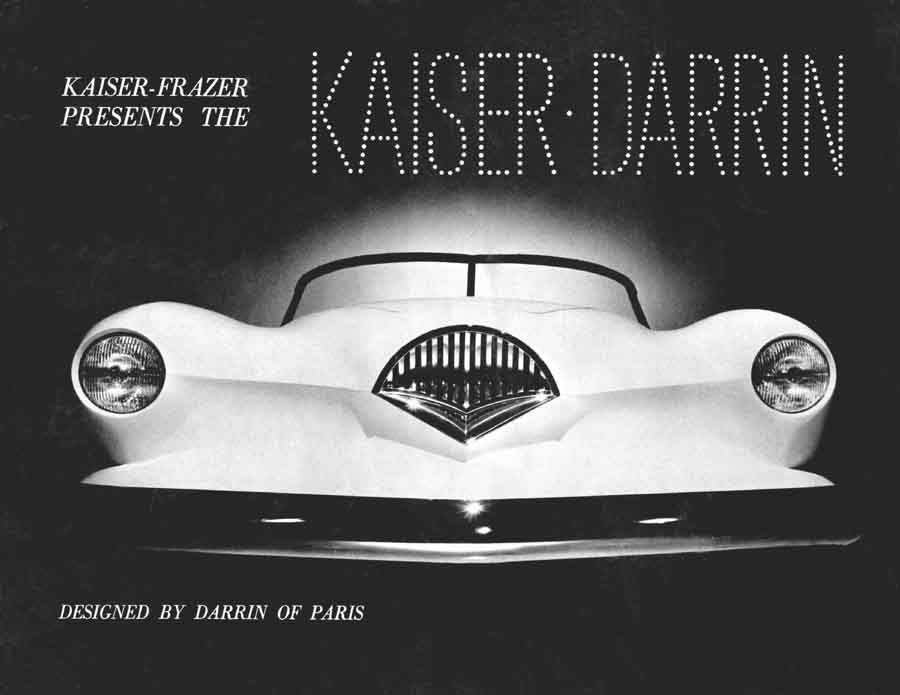

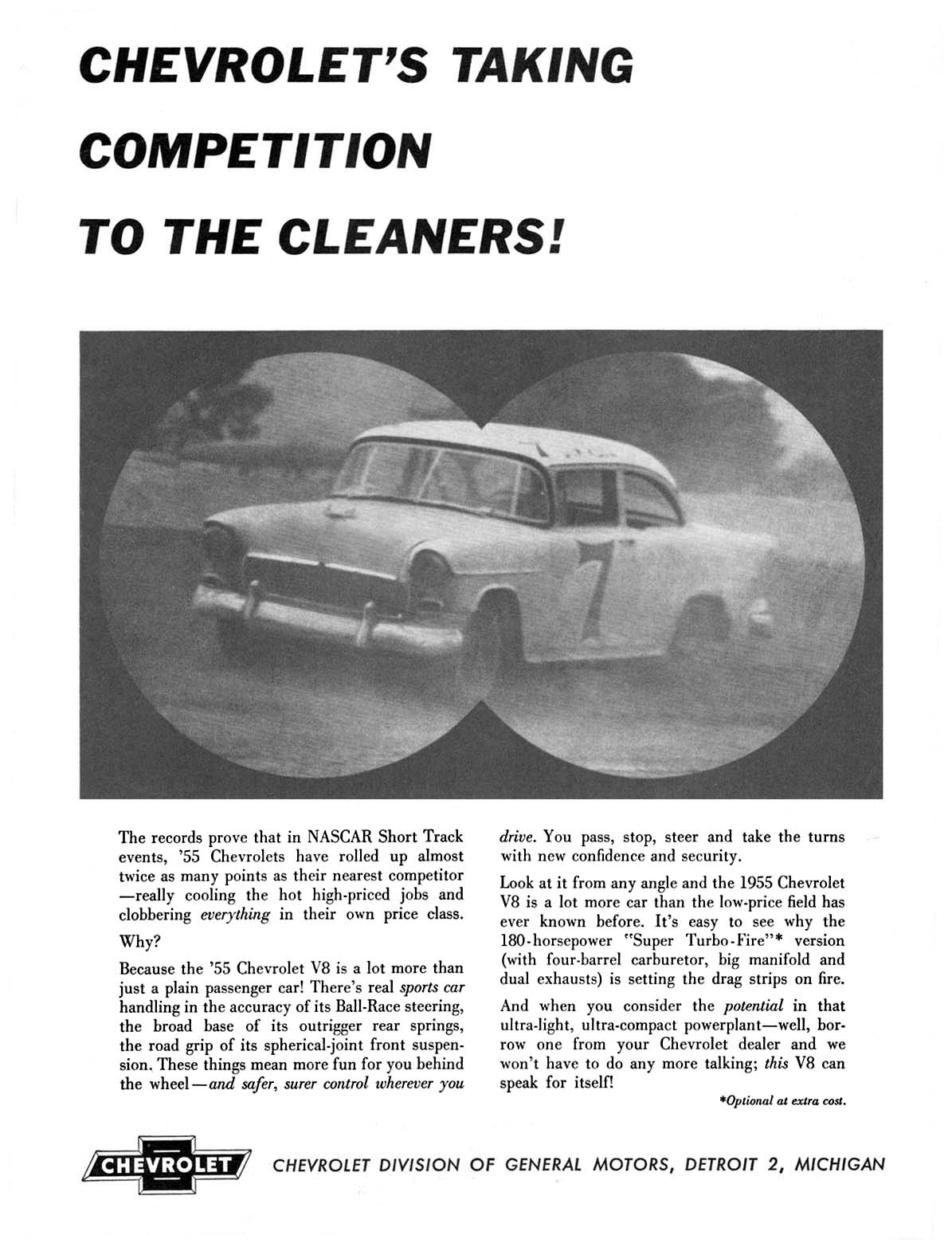

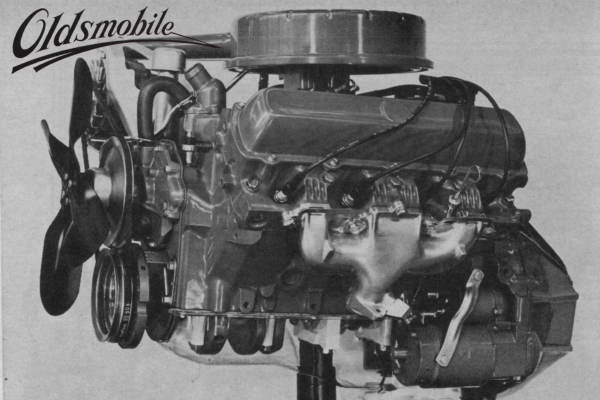

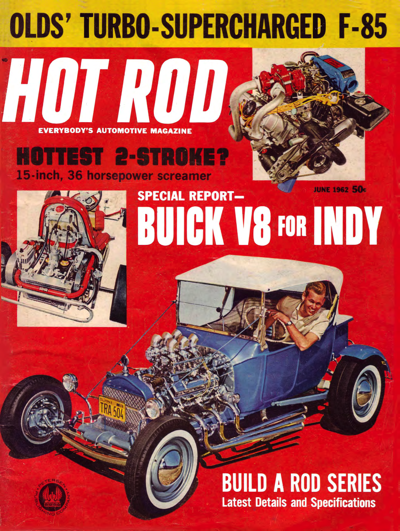

Jim Wangers Image 5

Jim’s intense interest in performance helped steer Chevy’s ad promotions towards competition exposure.

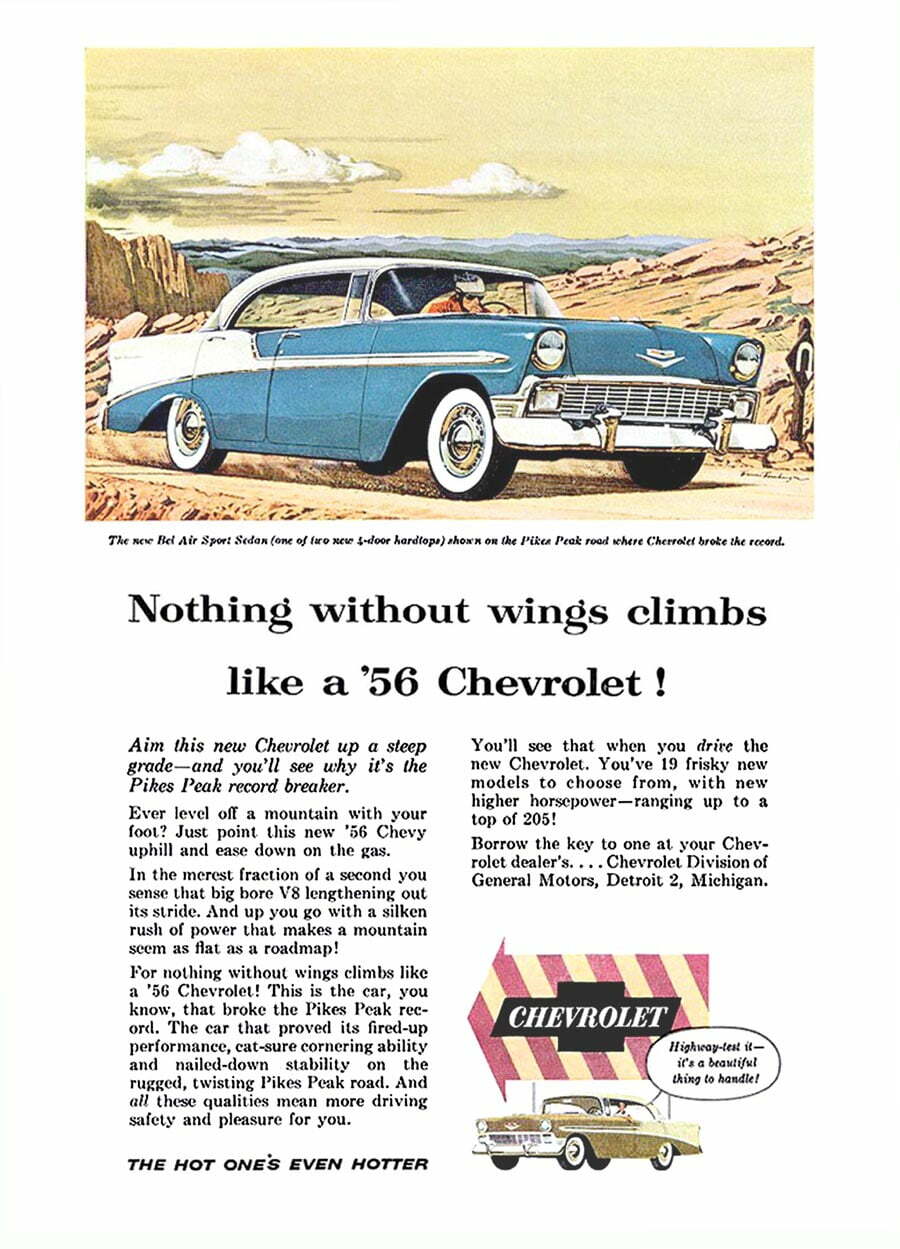

Jim Wangers Image 6

Chevrolet made good use of one of Jim’s early promotion campaign proposals. The Pike’s Peak hillclimb competition was custom tailored for Chevy’s hot new V8 engine.

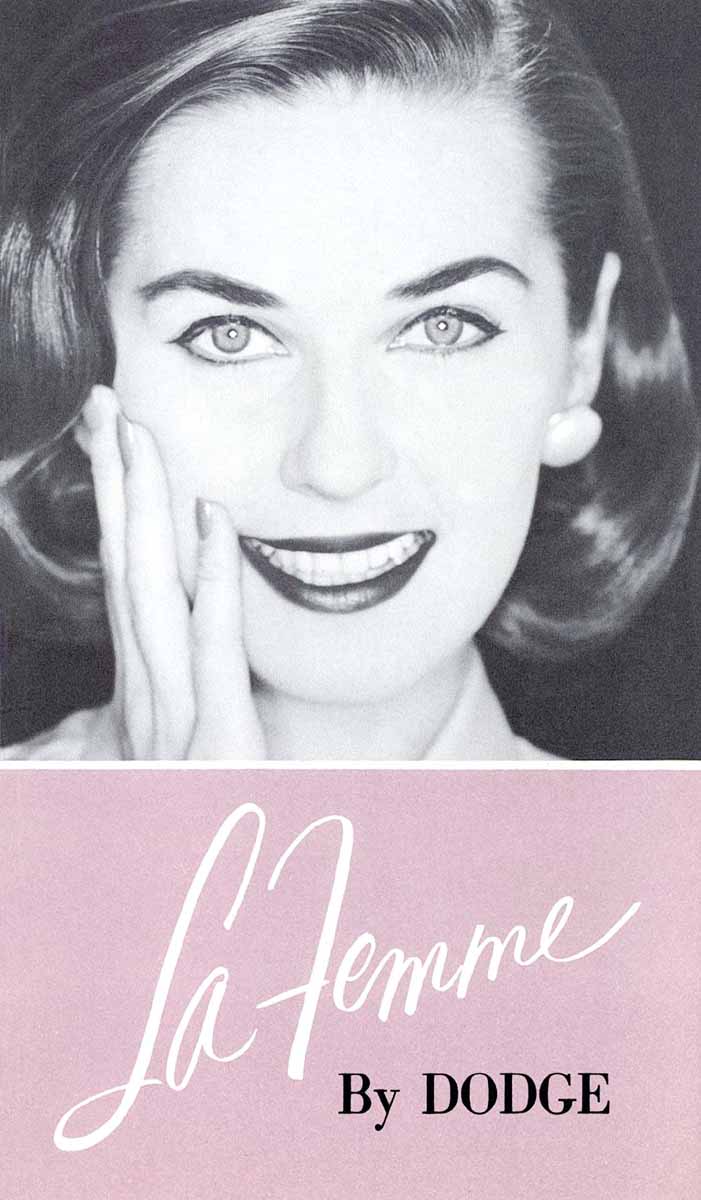

Jim Wangers Image 7

Focused marketing campaigns and dedicated vehicle models became an important part of Jim’s portfolio.

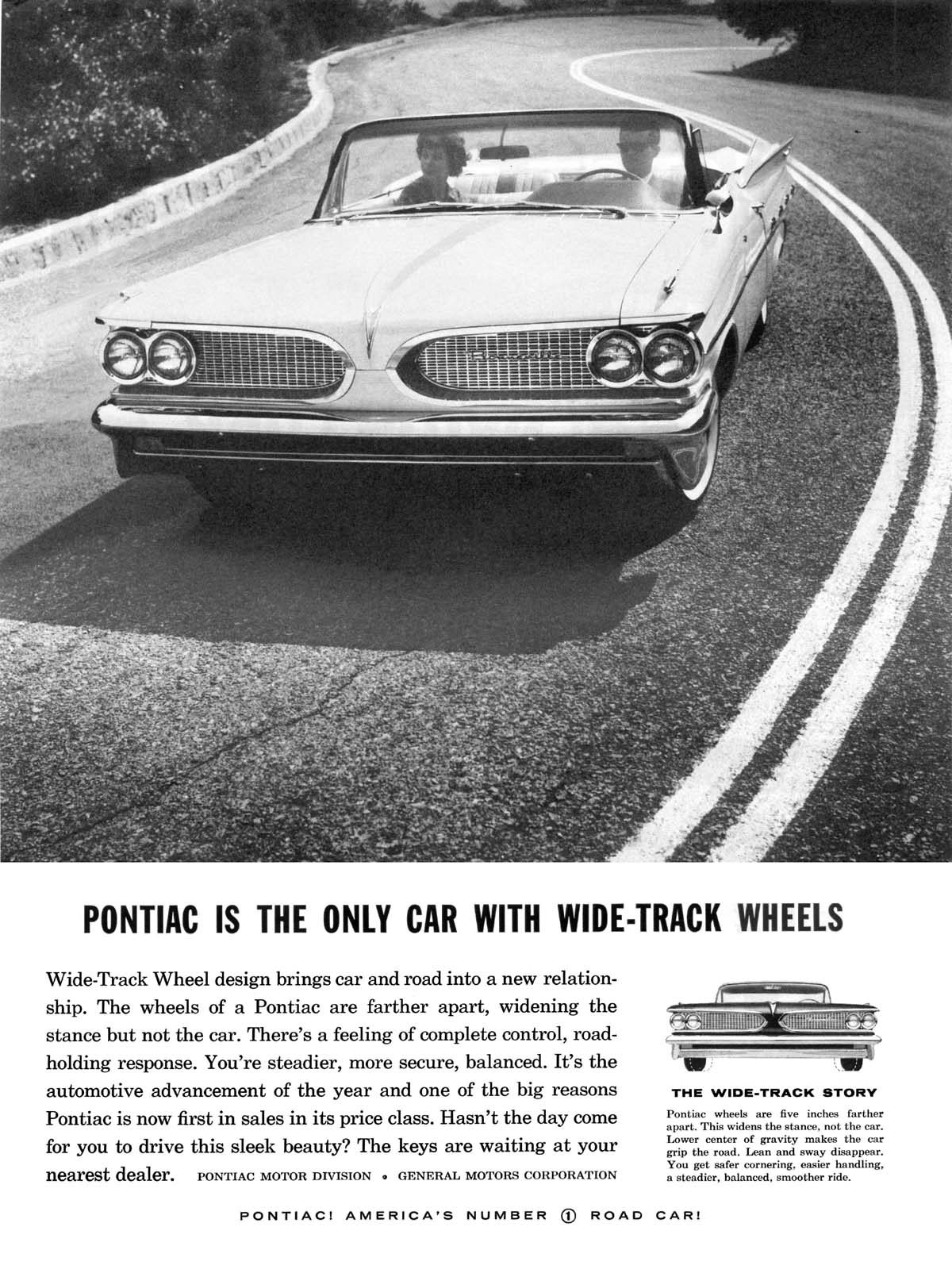

Jim Wangers Image 9

1959 Pontiac magazine ad emphasizes the new “Wide-track Pontiac” promotional campaign.

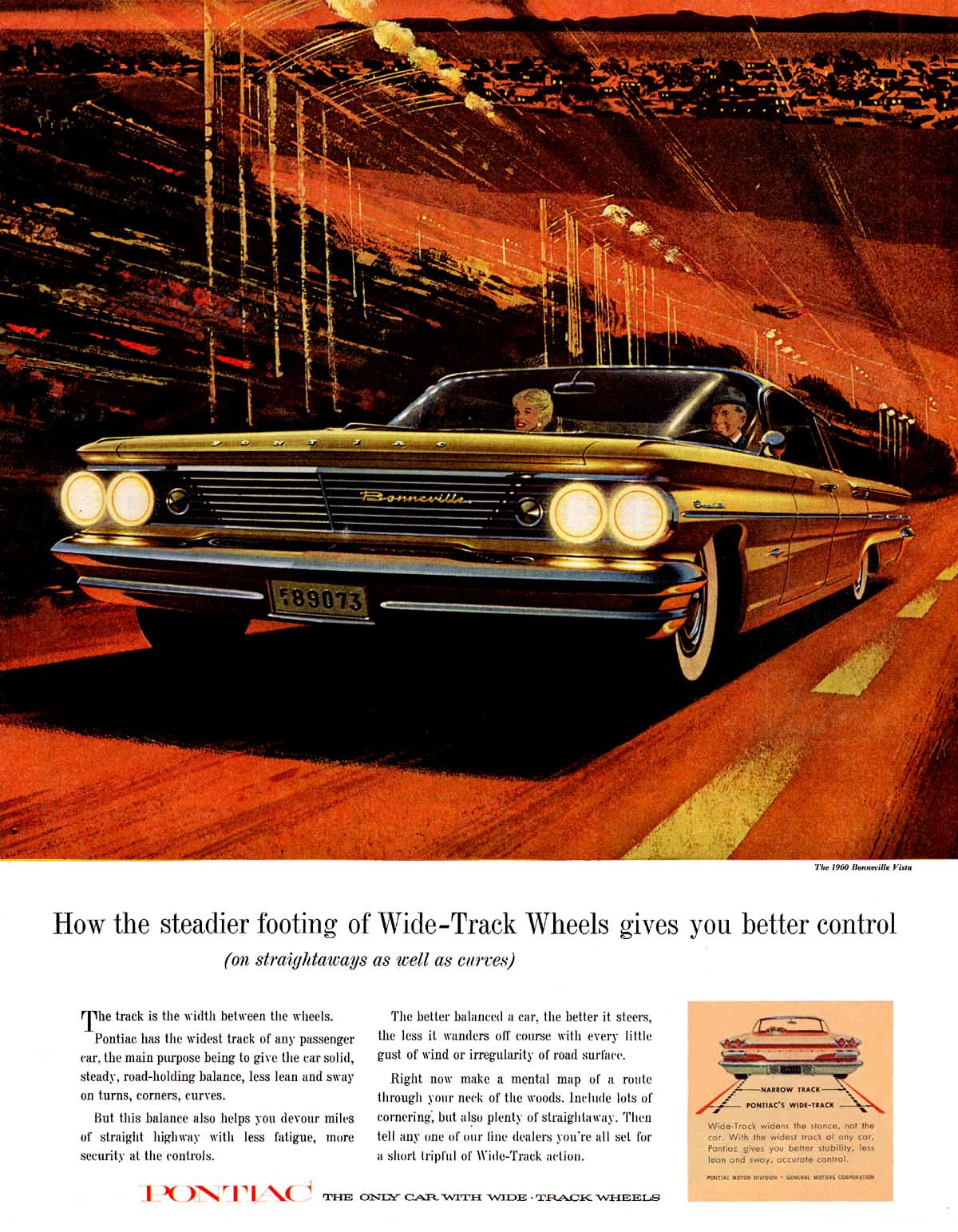

Jim Wangers Image 10

This 1960 ad showcases the artistic talents of Art Fitzpatrick and Van Kauffman in this dramatic “red sunset” illustration.

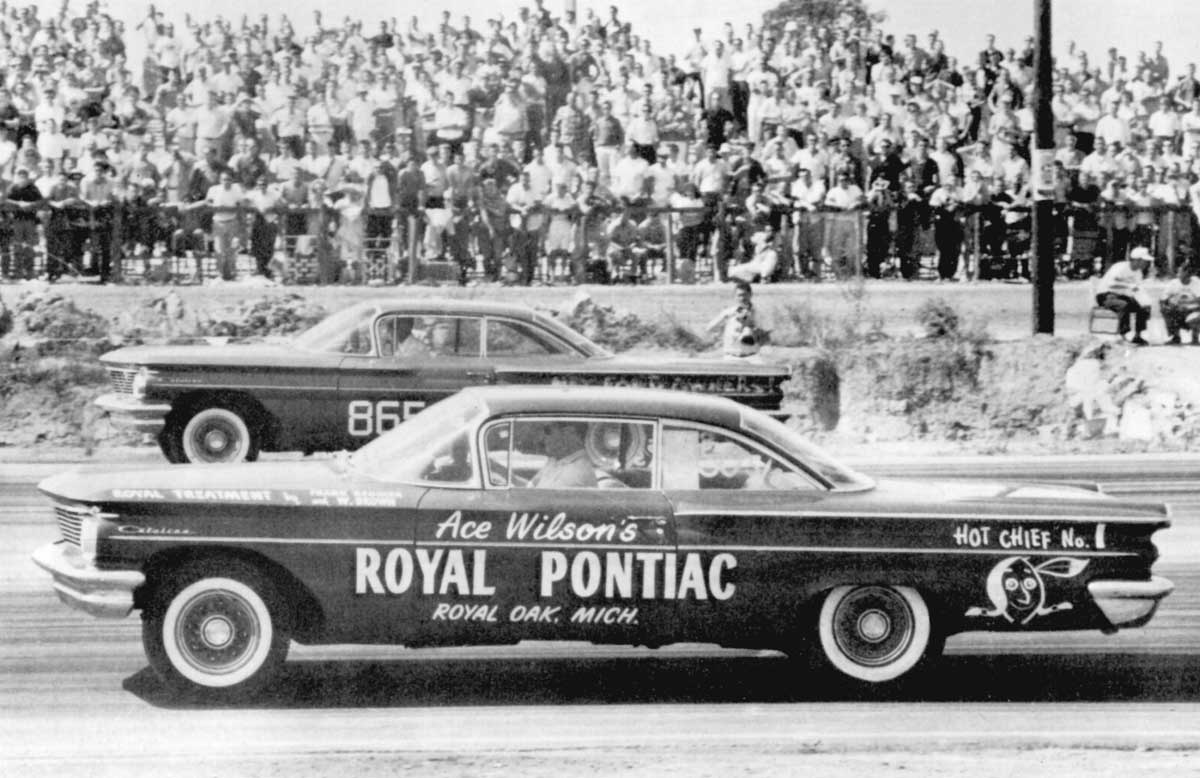

Jim Wangers Image 12

Hot-shoe ad man, Jim Wangers, is photographed as he pilots the “Hot Chief #1” Pontiac Catalina during “Super Duty Monday,” Labor Day 1960

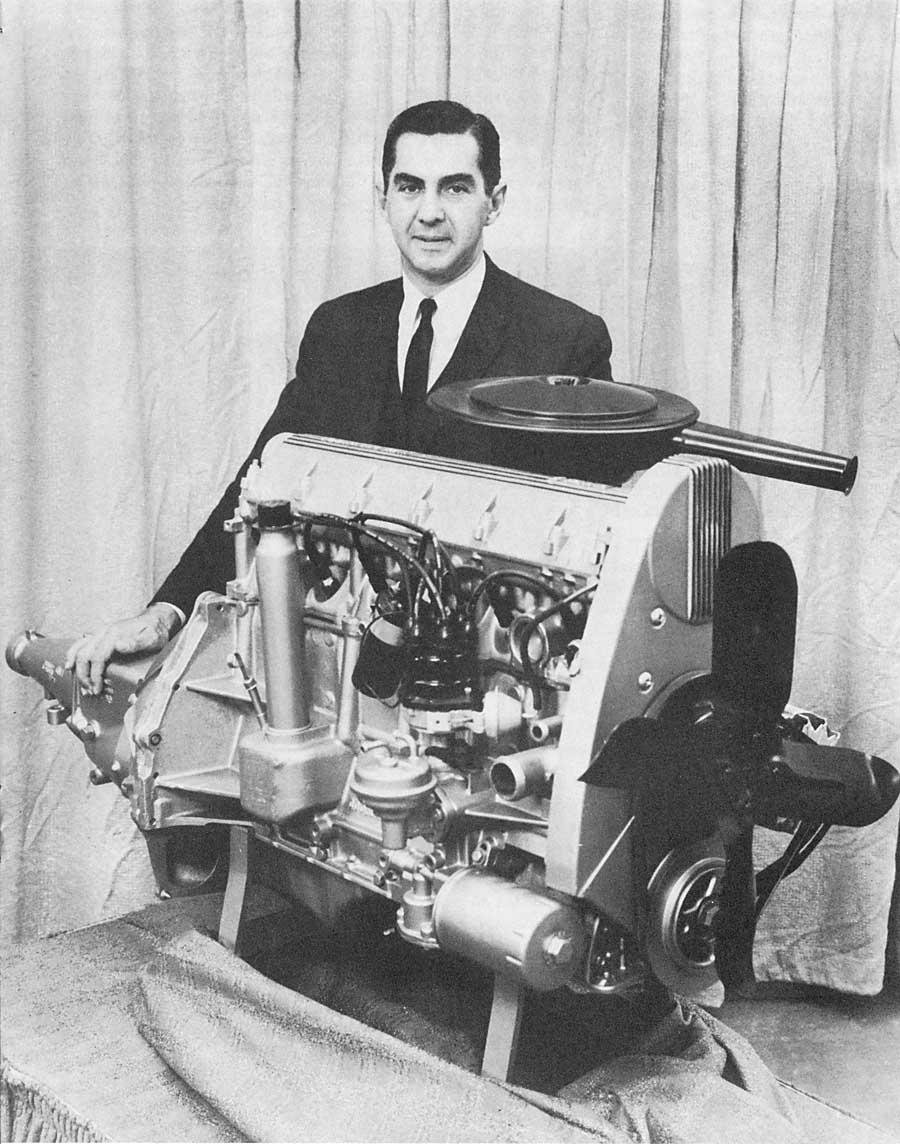

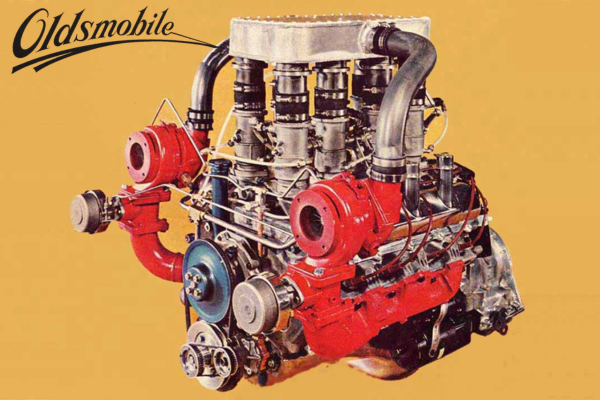

Jim Wangers Image 13

Pontiac division General Manager, John DeLorean. Shown here with the division’s revolutionary new 230c.i. OHC six of 1966.