When people talk about the birth of the American automobile, one name almost always comes up: Henry Ford. And rightfully so—Ford’s assembly line transformed the way cars were made. But tucked just before Ford in the history books is another name, one that doesn’t get the spotlight nearly as often: Ransom Eli Olds.

Olds was more than just another tinkerer trying to turn a “horseless carriage” into a business. He was a visionary who laid the groundwork for mass production, introduced America to its first popular, affordable car, and helped turn Lansing, Michigan, into a motor city before Detroit claimed the crown. This is his story.

Early Life: A Mechanic at Heart

Ransom Eli Olds was born on June 3, 1864, in Geneva, Ohio. When he was still a boy, his family moved to Lansing, Michigan, where his father opened a small machine shop. It was in that shop that Ransom grew up surrounded by the smell of oil, the clang of metal, and the buzz of invention.

Unlike many kids of his day, Ransom wasn’t destined for farm life or trade school. He spent his time absorbed in machinery, fascinated by how engines worked. By the time he was in his early twenties, he wasn’t just learning from his father—he was inventing on his own.

One anecdote often told about Olds is that he built his very first gasoline-powered vehicle in 1896 and promptly drove it through the streets of Lansing. Imagine the scene: horse-drawn wagons pulling to the side, pedestrians gawking at this noisy contraption rattling down Michigan Avenue. For a city used to blacksmiths and carriages, Olds’ invention must have looked like a machine from the future.

First Forays into Automobiles

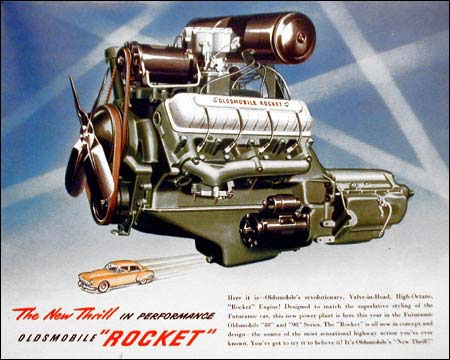

Before gasoline engines dominated, steam was the favored power source for early automobiles. Olds experimented with steam-powered cars in the 1880s and even built a steam-powered road vehicle around 1887. But he quickly recognized the limitations of steam—slow startup times, bulky boilers, and safety issues. Gasoline, on the other hand, seemed to offer speed and efficiency, and Olds was one of the first American inventors to bet on it.

In 1897, he officially founded the Olds Motor Vehicle Company in Lansing. That move set him on a collision course with history, even if success didn’t come overnight. At this time, cars were still luxuries for the wealthy. The challenge wasn’t just building a car—it was making one reliable, affordable, and appealing to everyday people.

The 1901 Factory Fire: Disaster That Shaped Destiny

In March of 1901, just as Olds Motor Works was gearing up to make its mark in Detroit, disaster struck. A massive fire swept through the company’s factory, destroying nearly everything in sight. Machinery, prototypes, blueprints—all went up in smoke. For most inventors and businessmen of the era, this would have been a crushing blow, the kind that ended careers before they had truly begun.

But fate—and quick-thinking employees—played a hand. In the rush to save what they could, workers managed to push just one car out of the burning building: a prototype of the Curved Dash Oldsmobile. Everything else was lost.

Instead of giving up, Olds took this as a sign. He doubled down on the Curved Dash and made it the company’s flagship. By focusing on a single, reliable model, Olds was able to streamline production and move forward quickly—an approach that foreshadowed Henry Ford’s later “Model T” strategy.

The fire, devastating as it was, forced clarity. Without it, Olds might have pursued too many models too soon, spreading his resources thin. Instead, the Curved Dash became America’s first mass-produced car, cementing Olds’ place in history.

Turning Tragedy into Opportunity

Later, Olds reflected that the fire, while catastrophic, may have saved the company by eliminating distractions. The Curved Dash, saved by chance and human effort, became the car that carried Oldsmobile to success. It’s one of those ironies of history—sometimes the greatest disasters clear the path for enduring achievements.

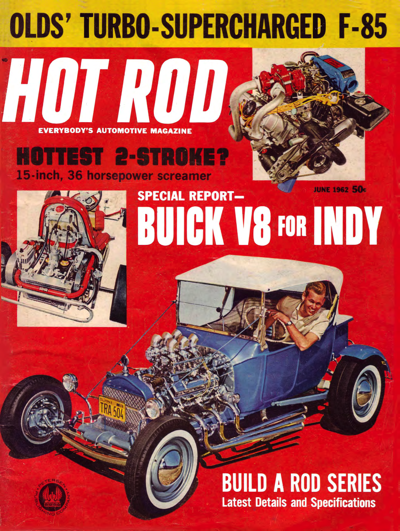

Oldsmobile and the Curved Dash

In 1899, investors persuaded Olds to move operations to Detroit, and the company was renamed Olds Motor Works. Two years later, in 1901, Olds introduced the car that would define his career: the Curved Dash Oldsmobile.

The Curved Dash wasn’t just another experimental runabout. It was simple, lightweight, and priced at $650—still a lot of money, but far more affordable than the luxurious machines being built for America’s elite. More importantly, it was reliable enough to win the confidence of average buyers.

Olds’ real stroke of genius wasn’t just the car itself but the way it was built. He employed an early form of the assembly line—workers stationed along the production floor, each responsible for specific steps in the build. This method allowed Olds to produce cars in larger numbers than his competitors. In 1901 alone, his factory turned out 425 Curved Dash Oldsmobiles. By 1904, that number had jumped to over 5,000.

For context, Henry Ford wouldn’t introduce his Model T until 1908. In many ways, the Curved Dash Olds was America’s first true “car for the people.”

Business Disagreements: Olds, Smith,

Samuel L. Smith: The Investor Who Took Control

When Olds moved his operations from Lansing to Detroit in 1899, it wasn’t entirely his idea. The relocation was largely financed by Samuel L. Smith, a lumber magnate turned investor. Smith put up most of the capital to establish Olds Motor Works and became president, while Olds served as vice president and general manager.

At first, the partnership worked. Smith’s money allowed Olds to build cars on a larger scale, and Olds’ inventive genius gave the company a competitive edge. But as production ramped up, Smith began clashing with Olds over business philosophy:

-

Olds wanted to standardize and mass-produce a small, affordable car (the Curved Dash).

-

Smith, however, preferred to chase the high-end luxury market, which had bigger profit margins per unit.

This tension simmered for years, and it eventually boiled over after the success of the Curved Dash. Smith and his board wanted to expand the lineup into bigger, flashier vehicles, while Olds insisted on sticking with what was working. By 1904, the disagreements became so sharp that Olds was effectively forced out of the company he had founded.

The Name Without the Man

Ransom Eli Olds once quipped that although his name stayed with Oldsmobile, “the company went one way and I went another.” The same could have been said by Louis Chevrolet. Both men saw their names rise to iconic status, even while they themselves were sidelined from the companies that bore their names.

The Birth of REO

But Olds wasn’t the type to retire quietly. That same year, he founded a new company in Lansing: the REO Motor Car Company, named after his initials (R.E.O.). The company quickly gained traction, producing cars and later trucks that built a reputation for durability and reliability.

One of REO’s most famous products was the REO Speed Wagon, a light-duty truck introduced in 1915. It became so well-known that decades later, a rock band in the 1970s adopted the name REO Speedwagon—a quirky cultural footnote that kept Olds’ legacy alive in pop culture.

Historical Context & Anecdote

Originally, Ransom Eli Olds intended to name his new enterprise the R. E. Olds Motor Car Company, but after objections from his former company, he settled on the initials REO. The branding of early REO models reflected a company still establishing its visual identity—transitioning from simple text to more decorative, recognizable emblems as it grew in popularity.

Influence on the Auto Industry

While Henry Ford perfected the moving assembly line, it was Ransom Eli Olds who first showed that automobiles could be built in volume. His use of standardized parts and organized production lines set the stage for the modern auto industry.

It’s worth noting that Ford himself admitted being inspired by Olds’ methods. Without Olds proving that mass production could work, Ford’s Model T might have faced a much steeper climb.

Olds also helped shape Lansing’s future. While Detroit became the hub of America’s auto industry, Lansing developed into a secondary motor city thanks in large part to Olds’ companies. Generations of families found work in Olds and REO plants, and the city’s identity became inseparable from the automobile.

Later Years and Legacy

Olds stepped down from day-to-day operations at REO in 1915 but remained an influential figure in the industry and his community. He invested in real estate, hotels, and other ventures, enjoying a level of wealth and prominence that allowed him to live comfortably while continuing to innovate on the sidelines.

When Olds passed away in 1950 at the age of 86, he left behind more than just a couple of car companies. He left a template for what the American car industry would become: innovative, industrialized, and deeply tied to the lives of ordinary people.

Although the Oldsmobile brand was retired by General Motors in 2004, its name carried more than a century of history. And REO’s trucks, while eventually absorbed into other companies, built a reputation strong enough to linger in memory long after production ceased.

Why Ransom Olds Matters Today

So why should we remember Ransom Eli Olds? Because his story is a reminder that history often overlooks the quiet pioneers. Olds wasn’t the flashiest businessman, and he didn’t have Ford’s larger-than-life persona. But without his Curved Dash Oldsmobile and his early embrace of mass production, the automobile might have taken a very different path in America.

The next time you see a classic Oldsmobile on the road or hear a REO Speedwagon song on the radio, remember the man behind those names. He was the bridge between invention and industry, the one who proved that the “horseless carriage” could be more than a rich man’s toy.

Closing Thoughts

Ransom Eli Olds may not have the household name recognition of Henry Ford, but he deserves a seat at the same table. He was one of the first to dream big, build boldly, and show the world what was possible. For automotive historians and enthusiasts alike, his life is a story worth retelling—because it reminds us that the cars we drive today were shaped not just by one man, but by a generation of inventors who dared to reimagine transportation.