Working with John DeLorean

by Eric White, Reprint with Society permission only

Society: What were your duties and responsibilities at the agency?

Jim Wangers: As a supervisor on the account, I really did, in fact, run the account. I was involved in every one of the decisions concerning what we were going to do with our money and what our theme lines were going to be. During that period, Pontiac never had a setback, starting really with the 1959 model year. Every year, if you go back and retrace the sales figures-in 1958 Pontiac sold 217,303 cars as a division, ridiculously low. In 1969, which was the last full model year before DeLorean went down to Chevrolet, we sold 870,528 cars, so they had moved from 217,000 to 870,000. Had DeLorean stayed at the division during the 1969 and ’70 model year, they would have climbed to over a million. They would have been the first division, other than Chevrolet, to climb up over a million. As it happened, Oldsmobile was then the first division. That didn’t happen, as you know, until the mid 1970’s, when Oldsmobile broke the million mark. That was because of the Cutlass Supreme.

DeLorean’s participation as chief engineer, starting from 1961 to ’65, and then as general manager from ’65 on through ’69, when he finally left and went down to Chevrolet, was really a very significant contribution. And being able to utilize the resources he had, that was one of his greatest assets. On those occasions when I would talk with him about why he didn’t he bring me out to the division and let me, in effect, be his marketing manager and let me over-see his marketing efforts, he’d laugh and say, “No you can’t. You’re much better off to me where you are, because I know I can hire a marketing guy. I’ve got an ad guy out here now, and sales guys. You’re not just another guy. I don’t need to waste you.” Plus the fact that he always liked the opportunity of letting me work outside of the system. That’s very important. I want to emphasize that structurally.

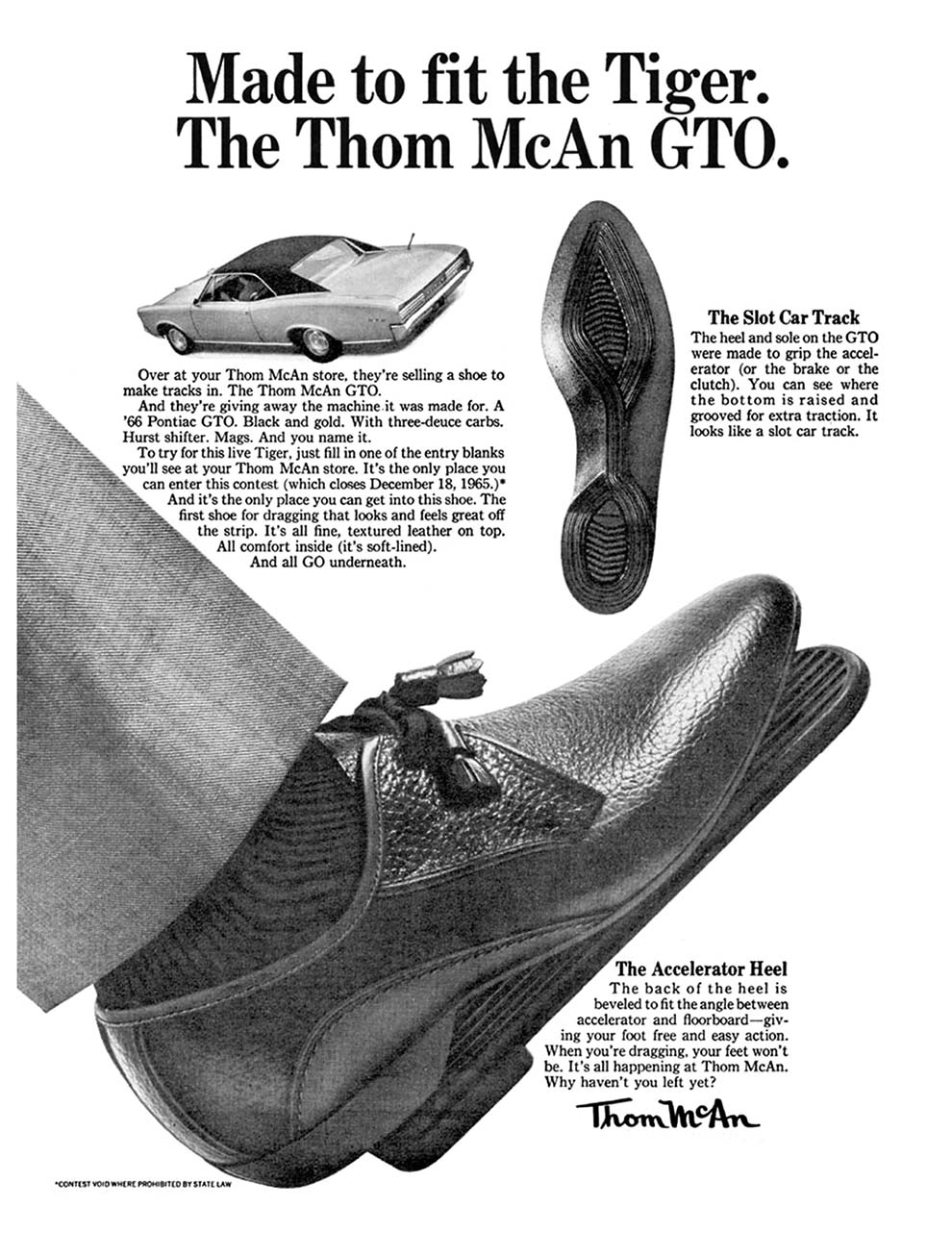

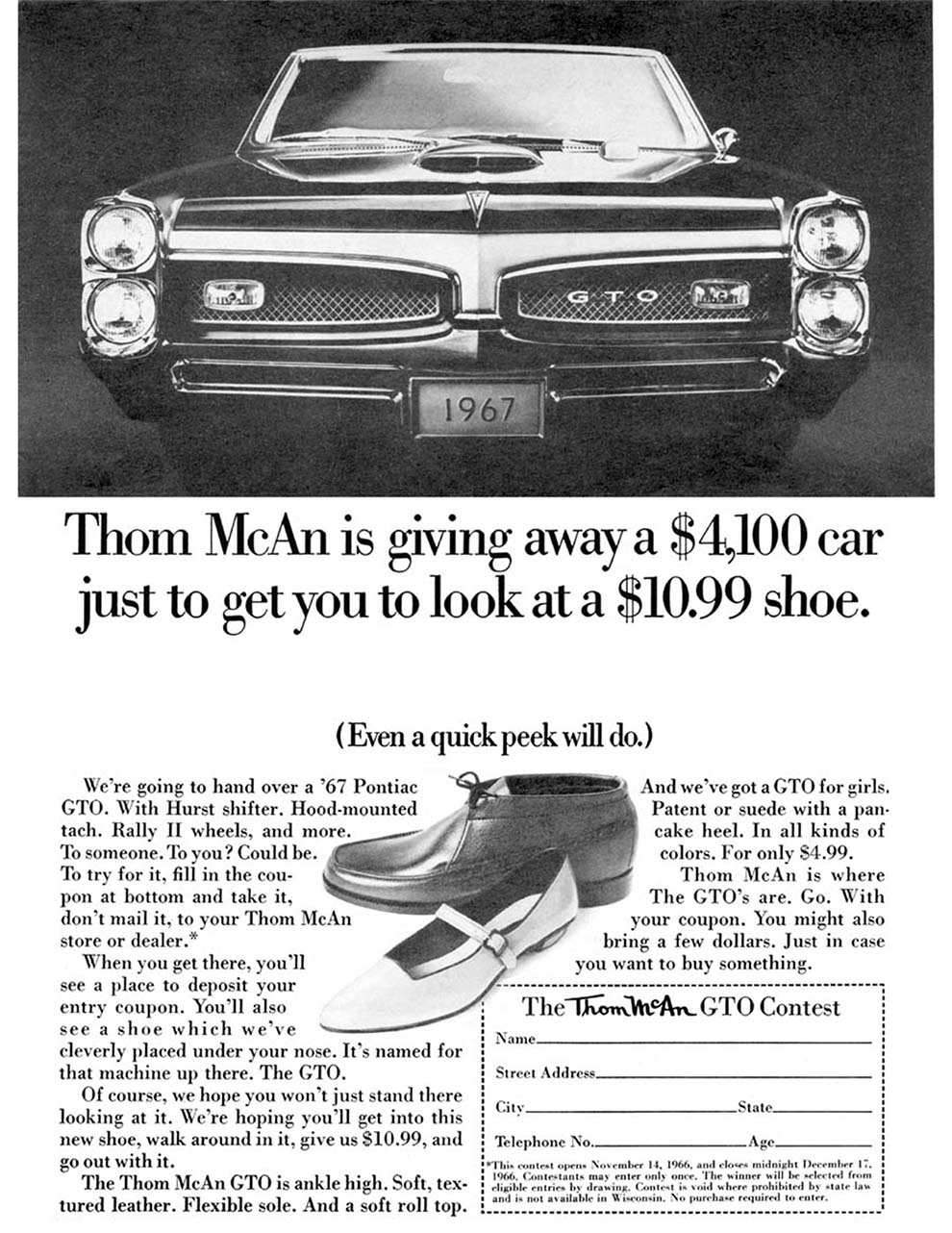

My relationship with John was just a sensational relationship. We were not what you would call personal friends. I didn’t play golf with him. I didn’t play bridge or poker with him at his home. We were not socially involved. We were just very, very good professional friends, with an incredible amount of mutual trust and mutual respect. When I wanted to do some of these crazy promotions I was able to pull off, like the Thom McAnn shoes, the MonkeeMobile, the GeeTO Tiger, and the Max Factor effort, I would go to him and say here’s what I want to do and here’s what it’s going to cost. We wouldn’t need to submit it to half a dozen places and have to fight it down.

I’ll never forget the Thom McAnn promotion, when we put that thing together. There were a lot of people at Pontiac, in the marketing and sales department, who said, “Does Pontiac want to get involved in a low line, kind of a common man’s shoe?” You know, the Thom McAnn shoe was really a kid’s shoe. Almost in a sense like the Payless Shoe Source is today, only it had a little bit more youth orientation. But it was a very avant-garde kind of a product that the young people hung on to. Thom McAnn was spending ridiculous money in that market segment using top forty radio. DeLorean was quick to see that.

I think that’s where I started to tell you the sales figures looked absolutely fantastic for Pontiac all through the 60’s. While it was basically a good decade for the industry. Everybody had a good year and a bad year, then perhaps another two good years, and then they’d drop. Pontiac’s sales curve looked just like this [moves hand in an upward arc]. Every year was better than the year before, with almost every one of our car lines.

DeLorean would say to me, “I’m gonna be the general manager.” When it got close, about the middle of his chief engineer’s tenure, one day he called me in and he says, “You know, I’m getting into a position where I need to know a little bit more about marketing, and about sales. I like advertising. I’m a good student of advertising, but I don’t really understand the theory or some of the creative needs. Can you help me a little bit on that?” So we structured a session. I used to come out to his office, sometimes as many as three times a week at six-thirty in the morning. I’d review a lot of the advertising that we were doing, along with a lot of the problems that we faced. I revealed why we were making decisions, or why we were doing some research, or why it was necessary for us to maybe go this way before we could go that way. At that time we were wide-tracking it right down the line. Every year we would come up with a different tag line structured around Wide-Track. First it was the “Wide-Track Wheels.” Then they became “Wide-Track Ride.” Then it became the “Wide-Track Pontiac.” We called them the “Great Wide-Trackers.” We would try to use as many different varieties of the wide-track concept as possible. The whole idea was that the “Wide-Track Pontiac” was a symbol of this whole new genre that was coming around with the image that Pontiac was trying to build. And boy he picked up on that. He was such a good student, and he had a real good mind. He totally understood it.

Of course, he had a great interest in television and entertainment. He liked entertainment people, he liked show people, and followed entertainment very significantly. It was an absolute delight to work with him, because he very quickly understood the role that marketing played.

He also quickly understood how important product marketing was in the role of image building. This is where there is such a big fall-down today-in Detroit particularly. There’s not enough people who really appreciate the product end of marketing, I mean, of product planning; why you do certain things with certain cars to make them more appealing in their market segment.

I guess the best example I could use-you’re familiar with this one-this 3800 engine that General Motors has got right now, this push rod engine that’s being used very heavily among the mid-sized cars; the Buick, Oldsmobile and Pontiac G-cars. A couple of years ago they came out with a supercharged version of that engine. It’s a very nice engine, it’s very pleasant, a good driver, got adequate performance, gets great gas mileage, and is incredibly smooth now that they put some balance shafts in it.

They came in with this supercharged package, which kind of put some sex into it, and put some excitement into it. Buick got that first because, basically, that’s kind of a Buick development that engine. They brought it out in a special version of the Park Avenue called the Ultra. Then they passed it along to the Oldsmobile 98 on their Touring Sedan, of which I think they sold two, maybe three. That was just not a very popular car. Finally it got around to going on the Pontiac Bonneville. Well, anybody with their head screwed on right at the corporation, in a marketing oriented capacity, could see that that engine belonged first on the Pontiac Bonneville. That was the perfect thing to give the Pontiac Bonneville a little one-upmanship. Here’s a car whose whole excuse for existence is kind of sporty package with performance overtones that had a lot of nice features; all of this in a day where they can’t have their own engines, their own transmissions, and their own suspensions. They’ve got to work within the corporation limitations and structure that the corporation makes available to these divisions, and give little features like this to support the images of each of these divisions. If they should come up with a real good suspension option like they did with the special electronically controlled suspension systems, you know, the road sensing systems, that should have gone on a Buick first! Cadillac gets excused from that because it’s out of that mid-sized segment. Cadillac’s got the Northstar and the Northstar system, which in themselves are unique. However, if there is a ride-control option, for example, that builds onto the comfort and the smoothness and the nicely modulated ride that can be built, well that belongs on the Buick. That’s Buick’s image-the overstuffed boulevard cruiser that gives you the ultimate, premier American motorcar of comfort and family reliability. Whereas, the sporty and performance oriented overtones, like that supercharger, belongs on the Pontiac Bonneville to give them the kind of an image that they’re so desperately needing to continue to promote.

Well DeLorean really understood that kind of stuff. That’s why when getting a GTO through, it was easy to get his support. Had he been running the division when I proposed that Royal Pontiac concept, well, that would have been on the road in no time. But I enjoyed one of those just incredibly magnificent relationships with John.

In all fairness, I’ll say that was exactly the wrong way to run a General Motors division. You don’t do it that way. You build teams, and work within the framework. When Pontiac was having this huge success, DeLorean had himself a cadre of maybe no more than ten or twelve guys from engineering, from marketing, from sales, from the controller’s office, from the production department, from manufacturing. When you have these meetings with these small groups in his office, the rest of the people just worked there. They were not involved. It’s the wrong way, according to the book, to run a GM division. Unfortunately when DeLorean left, all these guys who had kind of been walked over and had been overlooked, they came out of the walls.

Of course it got to be a pretty difficult environment to live in if you were one of the insiders and now suddenly were not necessarily protected. That was particularly true in my case. I had a difficult time, because I had not been an employee of Pontiac, but an agency guy. A lot of people took resentment to that. Yet, the guys with whom I had worked, the guys on those product planning committees and the guys who were supportive of a lot of those special efforts, were quick to recognize that I had made a fairly significant contribution. But I have to tell you that the day the door hit DeLorean in the ass for the last time at Pontiac, my life wasn’t worth a plug nickel there.

DeLorean had made it easy for me to go to Chevrolet. He wanted me to do exactly what I had done for him at Pontiac, to go to the ad agency at Chevrolet. I drew a line there, I said I don’t feel that that’s a smart move. I really didn’t want to go down there [Campbell-Ewald] and get into a situation. At McManus I’d been at the agency for many years before DeLorean took over, and of course it was easy for me to rise within the organization. The president of the agency, who later went on to become the chairman, Ernie Jones, he understood, he knew the situation. He says, “Hey, you’ve got a rapport there we can’t walk away from. You hang in there.” He knew that I was not going to do anything stupid, and any time there were any major decisions to be made I’d be there checking with him. My communications were good. It worked out very, very nicely. The situation at Chevrolet would not have worked that well. I would have walked into an agency where I didn’t really know a lot of the people. And here just because there’s a new General Manager of the division, there’s a new sonofabitch running the account; that’s not gonna work. I tried to make that clear to DeLorean.

I asked him on many occasions to try to find a spot for me within the division, which turned out to be a little tough for him to do. This was a period where he had gone through some personal situations, which the corporation didn’t like. There was a separation from his wife and ultimate divorce. Then there was the marriage with the young gal, Kelly Harmon. While he was doing a sensational job, and went on to do just as good a job at Chevrolet as he had done at Pontiac, he could not get a couple of the things that he wanted to do done.

One of those things was to get me into the division at the corporation. I made a huge mistake myself, and this was naive on my part. I wasn’t really as smart and sharp as I thought I was. Had I been committed to doing consulting work, which is what I’ve done for almost the last twenty years, I would have said, “OK John, set me up as a consultant. I’ll report directly to you. You can pay me through the ad agency through your ad budget. I’ll sit on the outside and work as a consultant, going directly through you and working with the agency. The agency will respect me, because they’ll know I’m not going to be in competition with them. I’m a consultant. I’m working for you on the outside.” Had I been smart enough to do that!

But you see in those days I was attracted by that warm womb of the security of working at a job. I didn’t recognize that it was just as easy to set yourself up in your own business, as I have done, quite frankly and very humbly I might say, quite successfully. I’ve been very fortunate, but I could have started it ten years earlier.

This was in 1970 when I left McManus finally. I did serve, sort of on a very temporary basis, as a consultant. I went down and had several talks with the Campbell-Ewald people, and it was apparent to me that they didn’t want me. I’m not sure I blame them. I could understand what the reality was. They respected me for not responding to John’s wishes. In fact, John got a hold of one of the guys who was working at a very high level at Campbell-Ewald at that time, a guy you probably know, David E. Davis, who had left Car & Driver and was working as a creative director on the Chevrolet account at Campbell-Ewald. He got a hold of Davis and said, “I want you to get Wangers involved. I want you to get him in at that agency. Convince him that he should join that agency.” Davis, however, wanted me at the agency like he wanted another head. While we had lots of talks about it, it was apparent to me that it was not the right thing to do.

As I sum up the Pontiac thing, I must say that the opportunity to do all of the nice things that I was able to do, and the way I was able to take advantage of so many of those good opportunities and tie-in promotional things, came about because I had this incredible support from DeLorean. I would simply go to him and say, “John here’s a program. Here’s what we’ve got to do. I can’t fool around. I’ve got to get a major presentation together. Trust me, it’s a great one. It’s gonna cost us this much money, and this is what I need. This is how much I need now.” He’d say, “Do it. Tell me about it after it’s done.”

Society: That sounds like the story of what happened after the uncomplimentary magazine road test of the GTO came out early in 1964 model year.

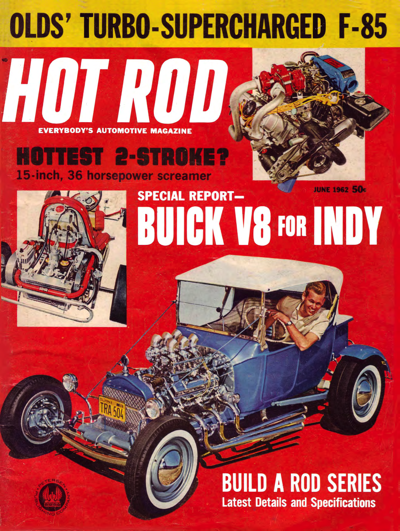

JW: That was a beautiful example. Hot Rod Magazine called the zone office and asked for a GTO. The zone manager, not really understanding the car said, “I’ve got a great one for you. My wife just took delivery of it.” He was being a good guy. He just didn’t understand. He gave them this car which was a two-speed automatic, with a four-barrel carburetor, wire wheel covers, weighed two tons, and ran like it. I’ll never forget that first line in Ray Brock’s story in Hot Rod Magazine on this tremendous new car was, “So what’s the big deal? I just road tested a new Pontiac GTO, and it doesn’t even beat my 327 Impala convertible which I ran last month.” You know he had a convertible. So, I remember, I charged into DeLorean’s office the next day after I got that book and I threw it down on his desk and I said, “For Christ’s sake John, how can you stand this? We bust our ass trying to get this car off the ground. We’re building these crazy images for it. We’re doing these great stories, like the Car & Driver story.” Then I say, “We get this kind of shit. We don’t deserve.” John says, “Well what do you want me to do about it?” I say, “Give me a car. I’ll show you how to get some press.” He says, “Well, why do you want only one?” So he opened up his drawer and he threw out a bunch of order forms, which were for engineering cars, and he says, “Here order yourself out a couple of cars.” So I started in 1964 with two. By the time DeLorean left the division in 1970, I had as many as twelve. Every year I’d get a 2+2, or a Grand Prix with a 428, or a Bonneville, and a GTO. I’d always have a bunch of cars. Of course, the P.R. department just hated my guts. And DeLorean didn’t care. That’s the way he ran that division. If they can’t do the job, you do it for them.

Society: What happened to all of those cars at the end of the year?

JW: We used to put them back.

Society: Didn’t Royal prep those press cars?

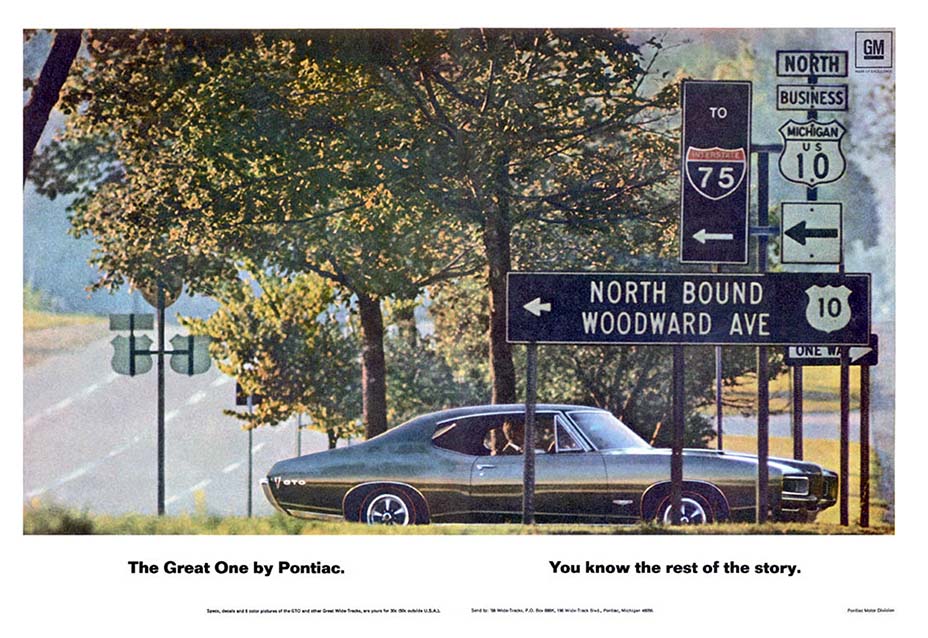

JW: The Royal Pontiac story is a whole different story in itself. It started out very honestly and very sincerely. Real early after the 1962 proclamation, in which we were told to get out of racing, and as the GTO became closer and closer to reality, it was apparent that we needed a front for the kind of activity we were doing, because Pontiac couldn’t do those kind of things. They couldn’t go to the races. They couldn’t prepare those special cars for the press and the magazines. The corporation had some very strict rules about it. It became very apparent to me, which DeLorean bought into a hundred percent, that we needed to hide this stuff behind Royal Pontiac. Here’s this very aggressive, active dealer, who’s constantly doing neat things with these cars. And of course, it got just incredible press for Pontiac, as well as for Royal. Some of the other dealers got pretty upset about it and pretty pissed. It was working so well. It was so easy for us to do anything special under the Royal activity, under the Royal nameplate. Most of those special things that were done to those cars were really done by the factory; showing Royal how to do certain things, and getting the cars prepared, and that kind of stuff. Although, Royal did do an awful lot of work in preparing an awful lot of very, very nice press cars. Every time a magazine writer came into town, I’d pick him up, bring him back to Royal, we’d give him a car, we’d go out on Woodward Avenue and have some fun with it and really get some action off. We’d take him to the right places. As a result, it became almost a ritual. It was such a fun thing. It worked. It just worked like gangbusters.

Society: That’s how you got involved in street racing.

JW: Exactly. I’ve often been told that I invented Woodward Avenue. [laughs] Anybody that tells you that Woodward Avenue was an organized test bed for the factory, that’s pure bull shit. Believe me, there were a bunch of cars out there that were factory related, because some of the engineering guys, even some of the marketing and sales guys, certainly myself, would take a car out there when we thought we had something kind of neat. We’d find out real quick whether it was competitive or not. It was our own little drag strip test bed, but there was nothing formal. We never got out there with cars from Chrysler runnin’ cars from Pontiac, nothing that dramatic or that romantic. It was just a very nice, kind of an informal setup. You always knew there were certain places where you’d run into somebody you knew. There was always something kind of interesting. Many times you never found out what was there, but there was occasionally a car that somebody wanted to get a run off with.

Society: Did the factory ever learn of any “tricks” from the people on the street?

JW: I think so. Sure, I think there were guys like myself that were constantly learning about some things. I don’t know that these tricks necessarily made it into production, but there were some things that some of the factory people were very interested in knowing about. In fact, the engineering people in particular were very close to the motor-sports activities, even when it was under the table. But Royal filled a magnificent hole for Pontiac during that period. This was another way for DeLorean to kinda get what he wanted.

It continued on after he became general manager and a guy by the name of Steve Malone became the chief engineer. DeLorean called Steve in one day and he says, “Look, I’ve got a bunch of special cars that are assigned to your budget that I want to stay that way. We’re going to assign them as P.R. cars and they’re going to go down to Royal Pontiac. You just go along with it, cooperate, and don’t give me any shit.” He says, “These cars will do us a lot of good. Do whatever Wangers asks you to do.” It was always kind of a low-keyed thing. Malone was the chief engineer at the division all the time DeLorean was general manager. He and DeLorean didn’t understand each other. He wasn’t smart enough to realize just how powerful John was.

When John was general manager, he pretty much served as chief engineer of the division also. On a couple of occasions Malone used to get up his dander and get real upset about some of these cars that were on his budget. He never saw them. He never had any idea what they were, what they were doing, all he knew was that they existed. Of course, he was reading about them a lot. Anyway, he complained on a couple of occasions to DeLorean, and DeLorean just ate him up. I mean it was almost embarrassing, “Damn it Steve, don’t ask any questions! You know what those cars are. That’s all you need to know. Just keep paying for them. They’re not coming out of your pocket. They’re coming out of your engineering budget. They’re doing us some good.” So as you can see, it was an absolutely magnificent relationship that just kept getting better and better the whole time it was going on.

Society: What was the process involved in producing a magazine or television ad?

JW: It’s easy to give one guy a lot of credit. A lot of these people have the idea that I sat there in the office all day and came up with these magnificently creative ideas. That I wrote this marvelous copy, and went out and took the damn pictures, and then put it all together and brought it out to the factory and sold ’em. No, that isn’t the way it worked at all. I had surrounded myself with a bunch of really top-notch creative people. More importantly, everybody in the agency really wanted to work on the Pontiac account, because we had such a great relationship with our client. Particularly when I was involved. I’d sit down with the creative people and I’d tell them what I knew the client wanted, because I had had this great communication, for the most part, with the client.

DeLorean would say to me, “Get what you want, do what you want, whatever you think. This is what we’re trying to get done. Come back and show me how you’re going to do it, but you come up with it.” It was that kind of relationship. I’d go back and communicate with my creative people. And of course, they loved it because they knew if they did what I told them he wanted done, they could do it any way they wanted. They’d take an idea that he and I had come up with, or an idea that I had, and then they’d go write it and create it and develop it. Of course, they had a ton of pride in their effort and pride of ownership in it. When they gave it to me, they knew pretty damn well I was gonna sell that ad. If I liked it, I was gonna sell that ad exactly the way they created it. Of course, that’s what creative people really love.

Society: So you were really the go-between.

JW: In a sense, I was really the go-between. Although I would always sit down with them ahead of time and tell them what I wanted. I had earned the respect of just about everybody in the agency. I don’t care if it was a media clerk or a copywriter or a copy chief or even the creative director, because they knew that I knew the product. They knew that I knew the division. They knew that I knew the market. They knew that I knew the people. When you’ve got that kind of rapport, that kind of respect, it’s pretty easy to get those people to bust their ass for you. I had just a magnificent relationship. I never had anybody say, “That f*#kin’ Wangers”, you know, “He keeps changin’ my ideas after he’s told me what to do.” They’d sit down and listen and occasionally they’d say, “Hey, how about if we went this way, or if we did it this way?” I’d say, “That’s a great thought. Do it. Give it back to me that way.” And that’s how we did some of those marvelous things. I didn’t sit down and write all of those ads and all of those headlines. I was as proud of every one of them as if I had done it, because I’d say to them, “Guys we’re arrogant, we’re winnin’, we’re beating them up. Keep coming back with more of those neat lines that you’re doing.” That’s all I’d say. “Hey, we’ve got a new car, we’re a little worried about its looks. Give us something that shows how it looks compared to the older ones.”

Invariably the GTO set the pattern for the advertising we were doing on every other car line, because it was exactly what we were trying to say about the car in sheet metal. It was a personification of the image running around on tires. It really was very easy to get everybody pretty excited. So I had a very nice relationship, but I earned it. I earned the reputation and I earned the image and the respect from these people, because they knew that I really knew what the wheelbase was or what the horsepower was. They didn’t have to go check, I knew and I would simply tell them. The product information guys were all good, because they didn’t have to bull shit me. They knew when they gave me something really good, if it was right, I’d know it. If it were not, I would tell them so. It was one of those nice happy situations. While I was involved in practically every decision that was made, I certainly didn’t write the ads or create the layouts or anything. But I knew exactly what was doing. It was also true of the catalogs and our television commercials. I didn’t go out and supervise every damn television shoot we did, but they were doing everything I knew I wanted done. The producers loved it, because we gave them such freedom and let them do such neat things as that drive-in thing, and the Paul Revere spot. So, it was just a magnificent relationship, which kind of came to a quick ending.

One story, which I didn’t get around to telling before now, represents exactly how DeLorean would support me. Towards the end of our tenure, the corporation got into a situation where they were concerned about our performance advertising. They were very concerned about our showing too much action, like flying dust and smoking tires on television, and screeching tires on radio. They set up a group that was under a guy by the name of Gayle Smith. He was charged with the responsibility of overlooking every one of the divisional ads that the corporation submitted, and then approving or rejecting them from a performance point of view.

If we showed the car and too much action, they’d say, “Hey guys, you can’t get away with that.” Well we were very conscious of that whole thing. That’s what gave away that Woodward Avenue ad. After that blew up we were suspect, of course, to everything we did. So I sent down this one ad which was called “A boy and his goat”. The ad got rejected, because they had gone to the trouble to look up what a goat was. They didn’t understand the ad. We didn’t bother to tell them that the goat was an accepted nickname for the car.

They said, “We can’t let you demean your product. The goat is the butt-end of a joke, and we can’t let you say that.” I wrote back to them and said, “Guys, you don’t totally understand. This is a nickname for the car. It’s come out of the market. The kids call it this themselves. We can communicate very well with them by recognizing this. It will make us look just that much more sophisticated, like we’re listening.” They came back, “No we’re not interested in that. You can’t do it.”

So I wrote a note on McManus letterhead to John DeLorean in which I explained this whole thing. Then I went out a little further, which was a big mistake that I made, and I learned very quickly from that lesson; don’t put it in writing. I said to John, “We can’t allow this to go on, because these are people who are totally unqualified to make these decisions, who are second-guessing our sophisticated efforts.” I said, “We’re good because we know how to communicate with our people. We’re talking to our owners and our market, and they respect us for that. We’re using the terms that we know they like and they use. Don’t let this get away from us. You’ve got to step in here and convince those people that this ad should run.” DeLorean used to wear blue shirts every day. Blue oxford button-downs. He had blue stationary and blue memo pads. It really worked, because any time you got in your mail a memo written on blue stationary, or you got a blue sticker on an envelope, you knew where it came from. He takes one of these blue sticker sheets and he pastes it right on my memo, which had the complete file, the ad, the communications with the corporation. He sends it to his ad manager with a note, “Wangers is right. Run this ad without their approval.” He sends it to the ad manager.

The ad manager is a nice guy, but he was a real whimp. He was not about to get his ass in a jam. So he picks up the phone and calls this guy, Gayle Smith, who’s a kind of a counterpart at the corporation level. He says, “I just wanted you to know that the general manager and that fellow at the agency he works with want me to run an ad that hasn’t had your approval. I want you to know it’s not me. I’m a good guy here. I wouldn’t do this. They’re makin’ me do it.” And so, Gayle says, “Send the file down here.” Downtown goes the file with my memo, which is a biting indictment of these guys, along with DeLorean’s approval on the thing. Of course they made a federal case out of it.

Next thing, I hear from my boss, who calls me and reads me the riot act. He says, “Not for what you did. I’d have done the same thing, but you don’t put it in writing, and you don’t do it on a company letterhead.” They [the corporation] wanted my ass. They wanted my job. He says, “Obviously, you’re not going to get fired, but I’ve got to give you a lesson here.” So I got a hold of DeLorean and told him the whole story. You know what his comment was? He says, “If I didn’t know you were in trouble all the time, I’d think you weren’t doing anything for me.” That was his attitude. He thought it was funny. That was the posture he used to take about the corporation. He thought that the bull shit that went into the corporation was just that, pure bull shit.

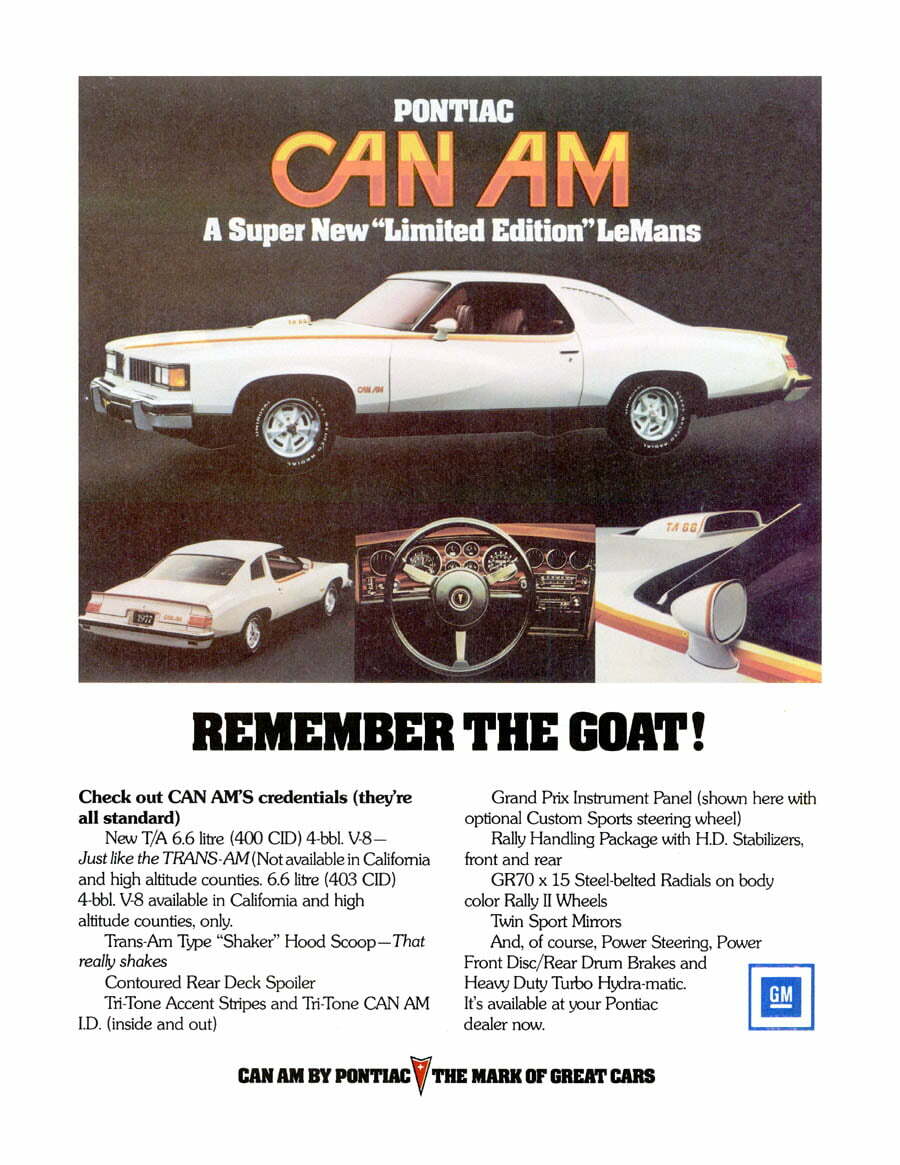

Society: Ultimately didn’t GM finally run an ad with the word goat in it?

JW: The goat that was in the ad that you saw was on an ad for the Can Am. That ad was not, repeat, not an official Pontiac ad. That ad was run by a company that I’m gonna get around to telling you about called Motortown. I started that company and we built that Can Am for Pontiac. That was the company that built the tool and couldn’t finish the spoiler. I was part owner of the company. That’s why I know so much about it. The car generated its own ad budget. In other words, we built it into the price that we charged Pontiac for building the car, so we had control over the ad budget. Therefore, we wrote the ad. And therefore, that was how we could use the word goat-“Remember the Goat”. We had to get Pontiac approval, and they didn’t want to approve it, but they said we’re not gonna tell you not to run it, and you don’t have to get corporate approval because you’re not showing any high performance or anything. That’s how that ran, and that’s the only ad you’ll ever see where the word goat appears in a Pontiac product ad. That was not a Pontiac-paid ad.

Society: By that time, everybody knew to what the word “goat” referred.

JW: Oh sure! By that time it was even more conclusive. That was in 1977 when the Can Am came out. Anyway, moving right along. After the Pontiac experience, I finally did not go with John. I said to myself at that time, O.K., I’ve had enough experience now, I’ve had a lifetime of fun in this business. Now it’s time for me to get real serious and go out and make some money. I want to become a dealer. That’s where the money was, you know, the guys that know how to make real money. What I didn’t realize was that to be a good dealer, you don’t want to like cars. A car is a dollar sign. What you want to do is just know how to turn that car fast and quick. Don’t ever get fond of it. Don’t get affectionate to it. Don’t start screwin’ around with it. Don’t start customizing it.

Anyway, through a lot of help from my good friend John DeLorean, who was now at Chevrolet, I found a Chevy dealership in Milwaukee, but it took me almost a full year to get that done. So, in that capacity, while I was traipsing back and forth to several big cities looking for a dealership-I wanted one in a major market-I signed on in a consulting capacity for my good friend George Hurst, who had run Hurst Performance. At that time one of the businesses they were in was the business of building limited production specialty vehicles, which started from the Hurst/Olds, which had already started before I left Pontiac.

END OF PART TWO

Topics discussed in Part Three:

- The 1968 Hurst/Olds, S/C Rambler and Rebel The Machine.

- Jim Wangers’ Chevrolet.

- The catalytic converter.

- Motortown Corporation.

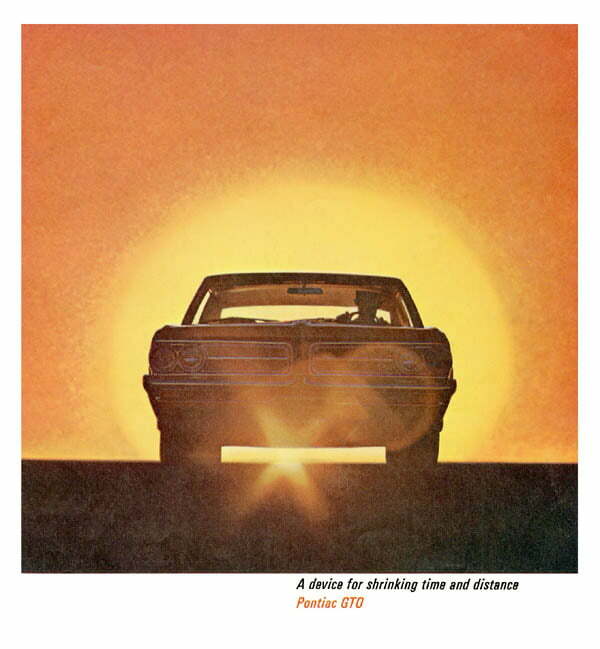

Jim Wangers Image 2-2

The 1964 LeMans GTO sales brochure. This brochure was released in two versions.

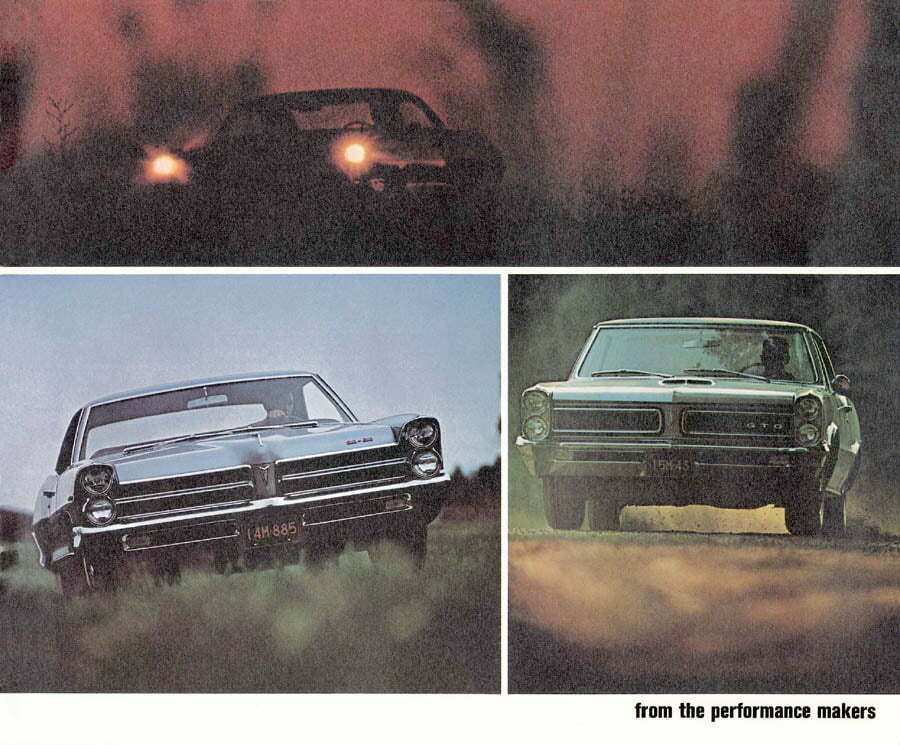

Jim Wangers Image 2-3

The first edition of Pontiac’s line of performance brochures. These brochures were issued from 1965-1971.

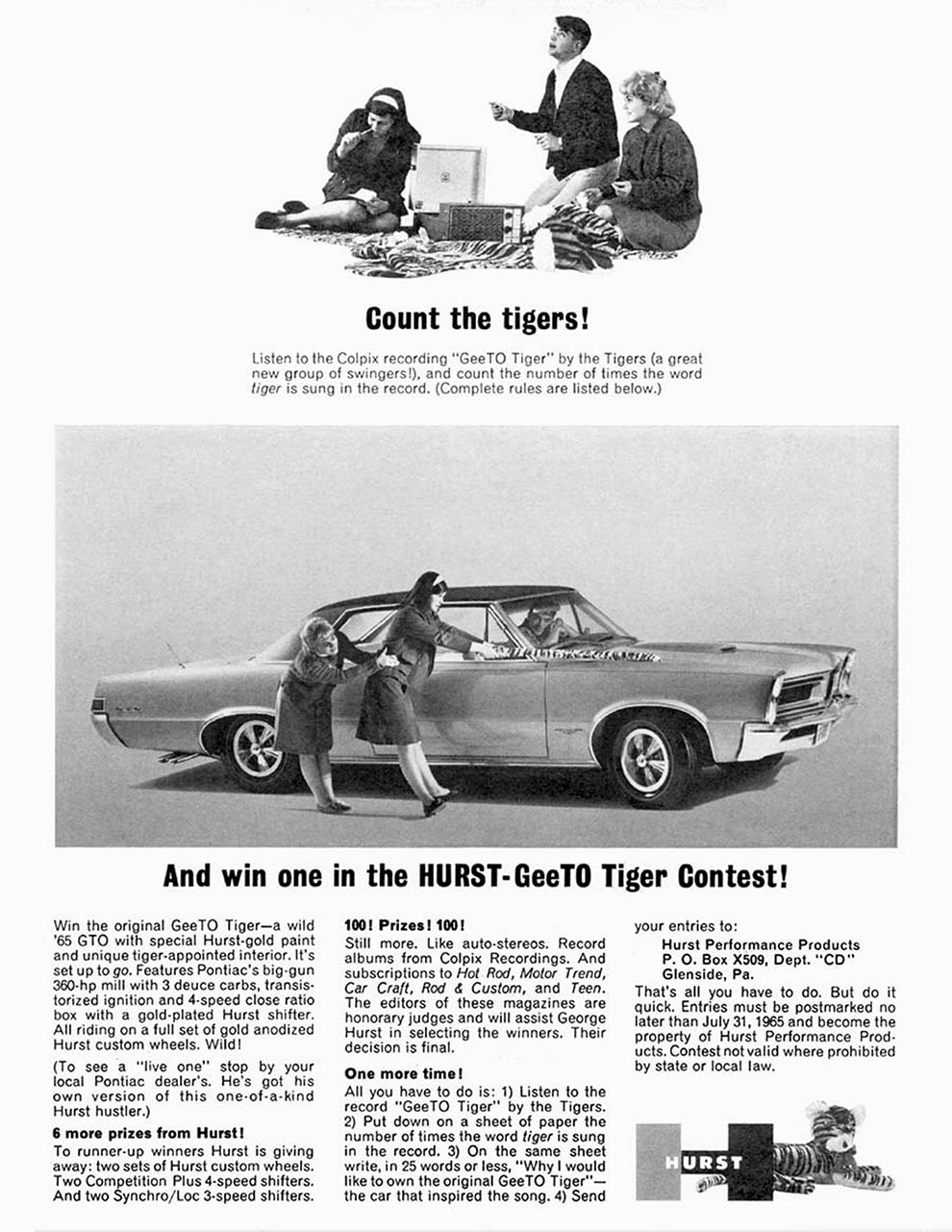

Jim Wangers Image 2-4

The famous Hurst promotion is explained in this 1965 magazine advertisement. Jim was a good friend of George Hurst.

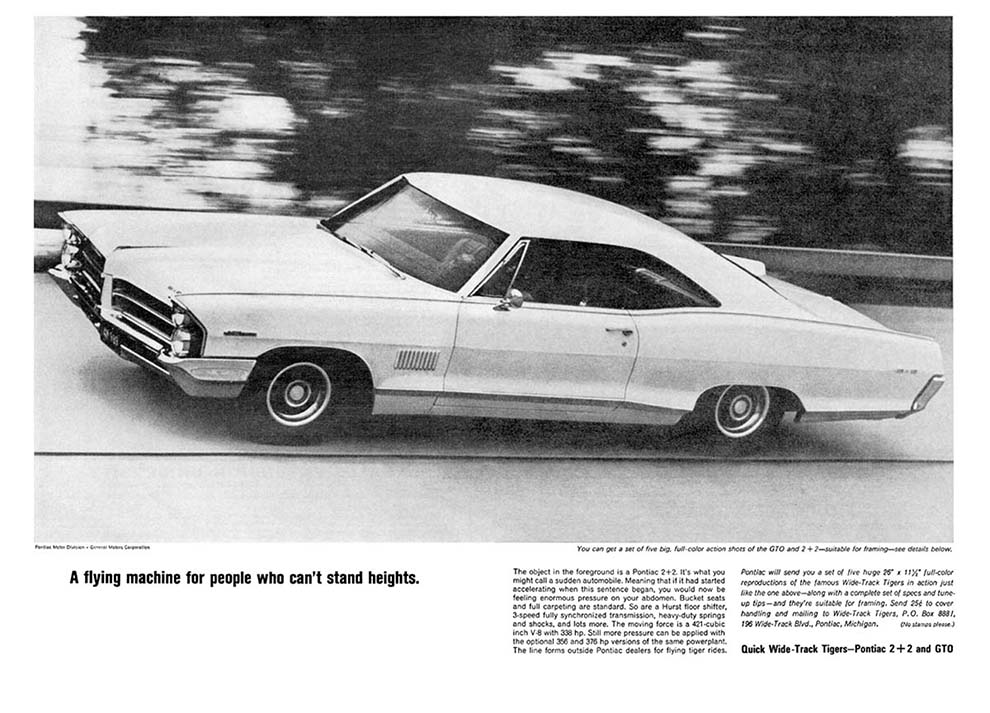

Jim Wangers Image 2-5

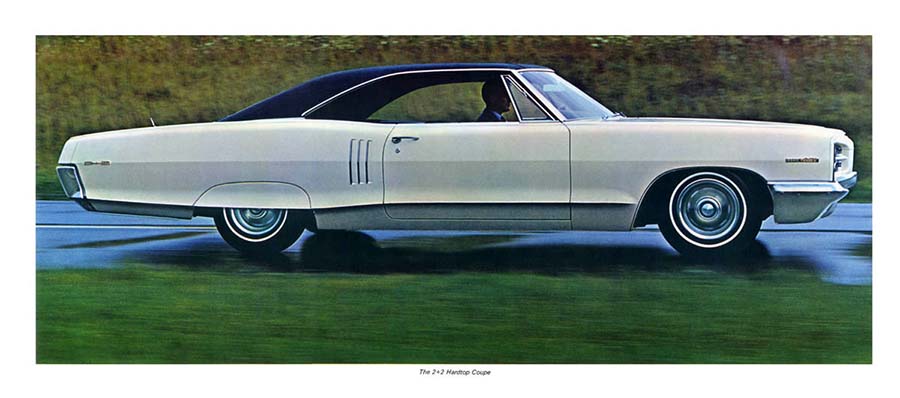

GTOs were not the only performance oriented vehicle offered by Pontiac in the 1960s. The Catalina 2+2 was marketed with zest by Jim Wangers and the McManus, John & Adams ad agency.

Jim Wangers Image 2-6

Here is the 1966 2+2 poster. This item was made available through the mail-in poster campaign that ran from 1965 through 1970.

Jim Wangers Image 2-7

Here is the 1966 Thom McAn GTO shoe campaign ad. Italian-style shoe was available at any Thom McAn shoe store near you. Associated contest gave away a new ’66 GTO.

Jim Wangers Image 2-8

The 1967 version of the GTO shoe ad from Thom McAn. Another GTO is offered as the grand prize this year

Jim Wangers Image 2-9

This is the now famous “Woodward Avenue” magazine ad from 1968. The ad ran for a very short time before complaints from various communities located along Woodward Ave forced its cancellation

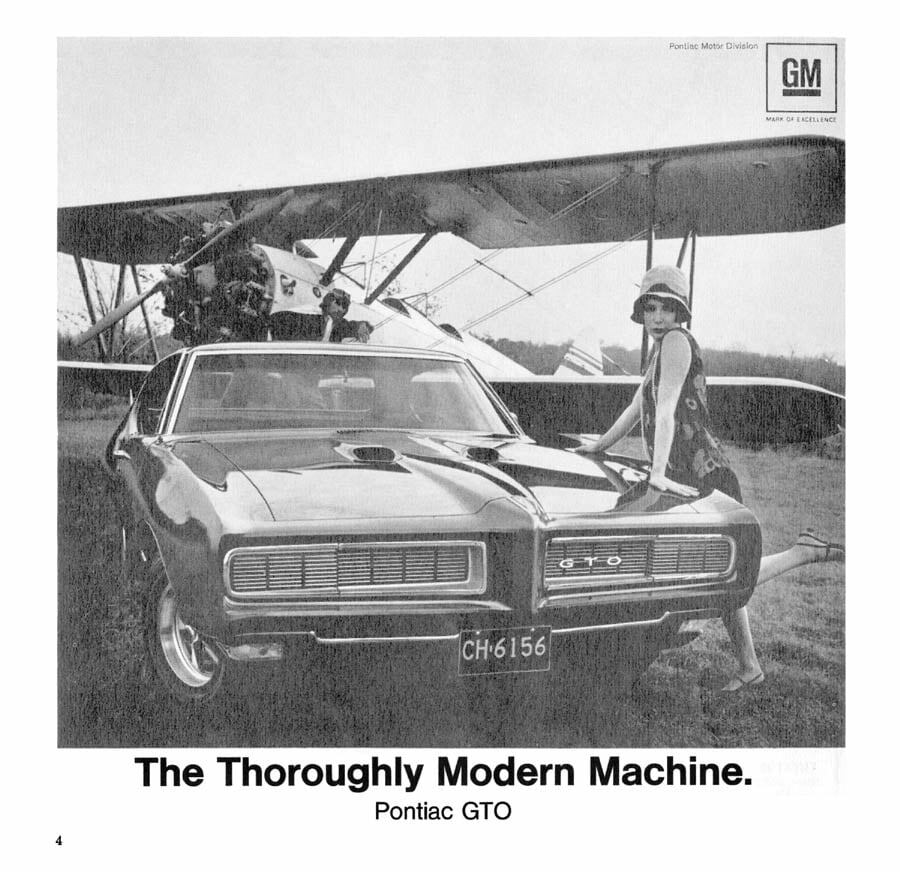

Jim Wangers Image 2-10

A rare ad obtained from Playbill magazine. The ad plays off the then popular Broadway production and movie “Thoroughly Modern Millie.”

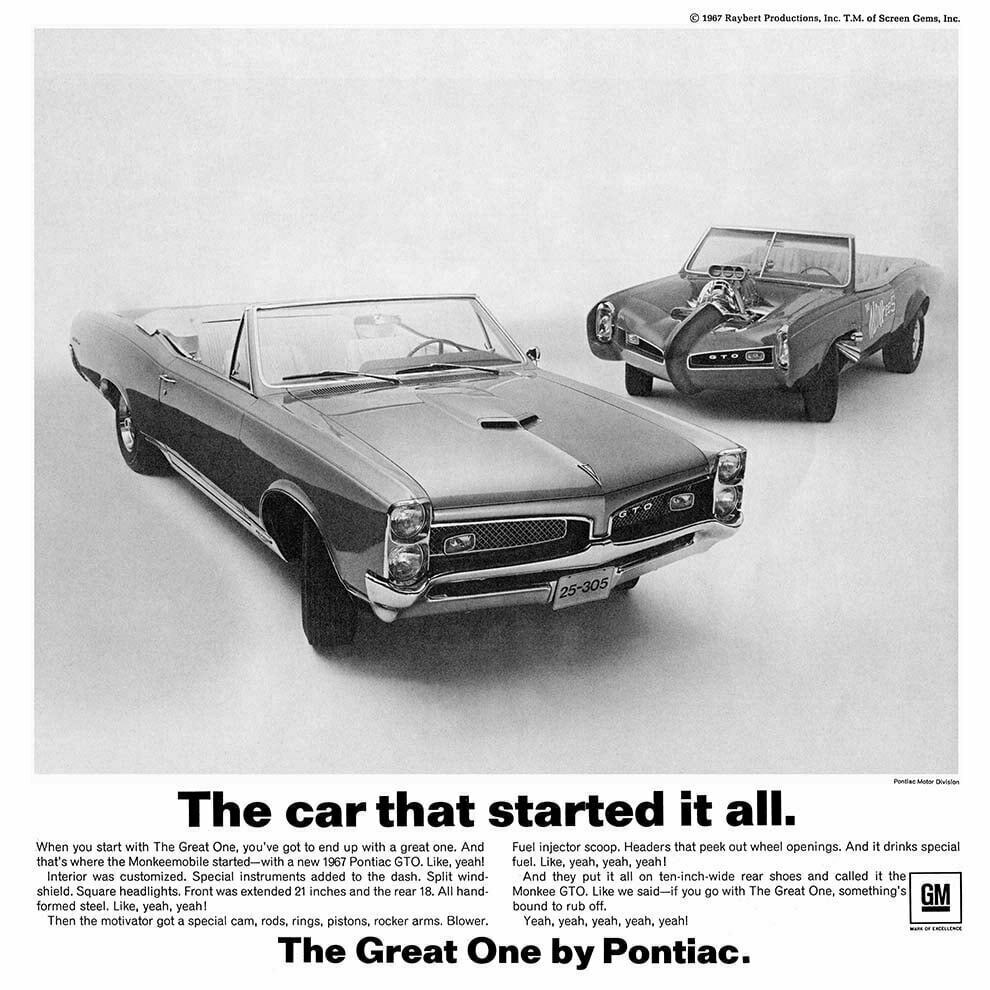

Jim Wangers Image 2-12

Extremely rare Pontiac ad promoting both the 1967 GTO convertible and the Monkeemobile. This ad is only found in the 1967 Monkees’ concert tour program.

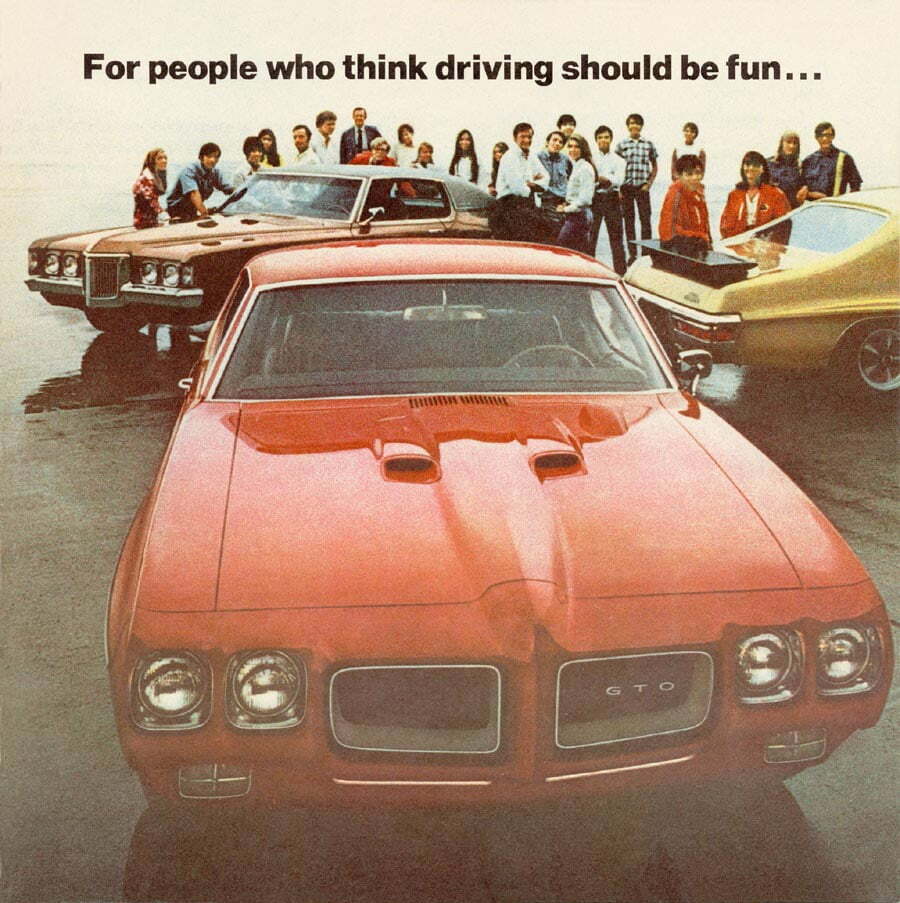

Jim Wangers Image 2-13

Here is perhaps the very best Performance brochure ever produced, the 1970 Pontiac piece.