Specialty Cars R Us

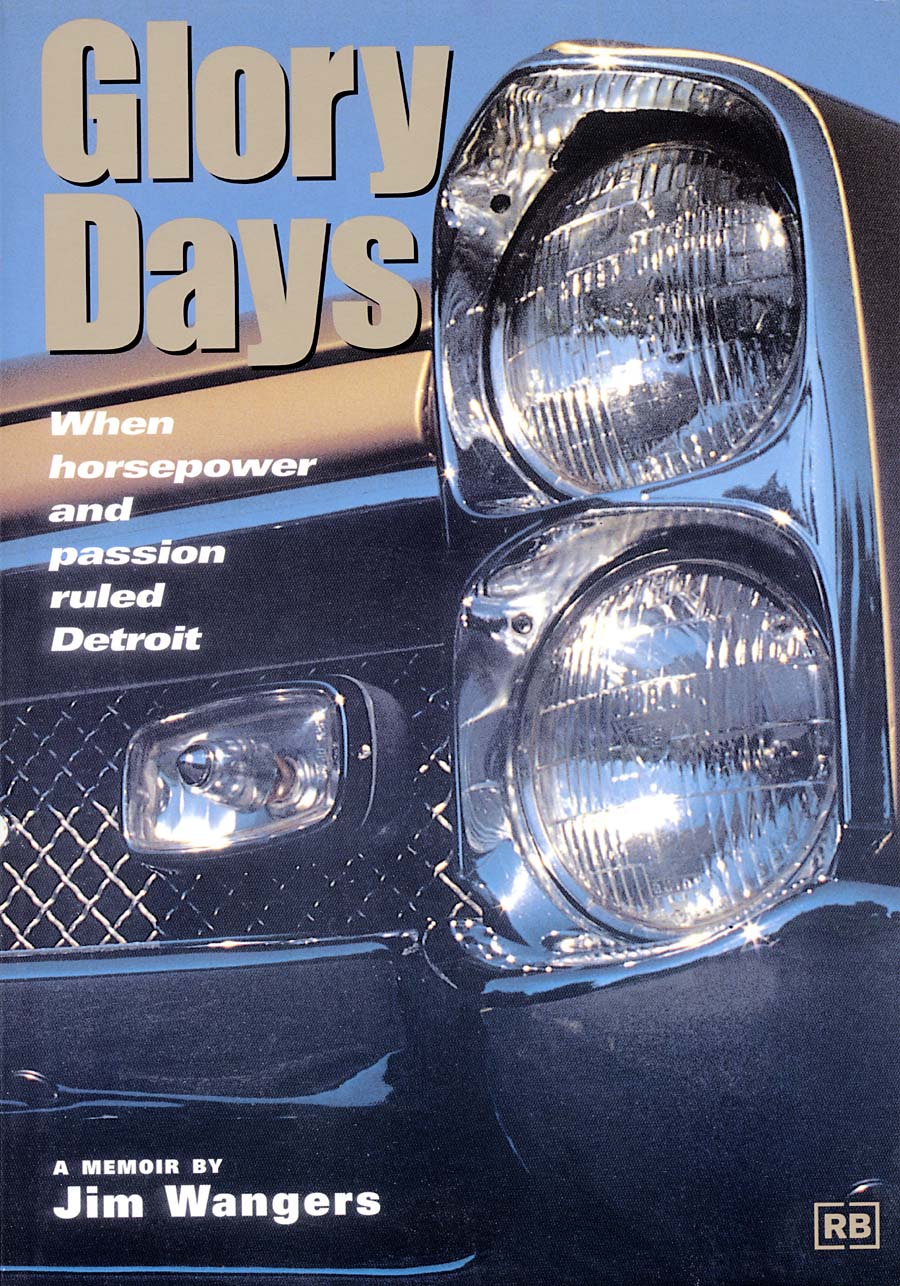

Enter Hurst, exit Motortown

by Eric White, Reprint with Society permission only

Society: How did the Hurst/Olds originate?

Jim Wangers: The way the Hurst/Olds came about, quite honestly, was because of a Pontiac rejection. One of the things that George Hurst was just hell-bent on doing, and I admire George for his perseverance and his fortitude; he wanted to build a car with his name on it. He wanted the name Hurst on some kind of a car. He had a tremendous ego, as you might appreciate. So right after we brought out the Firebird, in late ’67 going into the ’68 model year, he wanted to build a 428 Firebird and call it the Hurst Firebird. DeLorean thought that was a swingin’ idea, as did I. So, George employed McManus and myself to put together a major presentation, with DeLorean’s approval, of course, whereby Hurst would buy a whole bunch of Firebirds, “Ram Air 400 Firebirds“ that would be shipped down to his plant.

We were going to do it in Warminster, Pennsylvania. He would also buy a bunch of 428 engines, and they would be shipped down there. They would convert these Firebirds, which were built with 400’s, since GM would not ship a car without an engine in it. It was against their rules, their bylaws.

Society: They wouldn’t build them as a fleet order?

JW: Nope, would not. Under no circumstances could that 428 be put in at the factory. They had to come out of the factory as sold units to Hurst with 400’s in them.

Society: Yet Chevrolet could get around this ban.

JW: Well, Chevrolet had some C.O.P.O., central office production options, they were able to invoke, but they were really doing it on a very few at a time. George wanted to build 500 of them.

So anyway, we put this whole presentation together with the idea that he was going to buy the cars, buy the engines, and we would ship them to him. The only thing we had asked the corporation to do was to buy the 400’s back from him and put them back into the production line, which was not too much to ask them to do. We went downtown and made this presentation to Pete Estes, who had just become kind of the liaison at the corporation between the general managers of the divisions and the corporation. This was a guy, that was moved up from one of the division general managers, who listened to all of the presentations and all of the ideas that the general managers of the divisions had. He would then make a decision on whether it should go any further, or whether it was a stupid idea and don’t even think about it, as it related to products.

So we went downtown. George Hurst, John DeLorean and myself had put this presentation together for the creation of the Hurst Firebird. Estes looked at DeLorean and he looked at me and he looked at George and he says, “Guys, I can’t do this. You guys [PMD] don’t need this. You’re selling the hell out of that Firebird. You don’t need another 428.” He wasn’t really tuned into the fact that we were doing it as much for George, who just wanted a car with his name on it. Pete says, “You know what, George, if you were to take this up to Oldsmobile and talk to them about doing something with that Cutlass, you know, that 442, those guys are really smarting up there about this Firebird. They want this car. They want an F-body of their own, and they can’t have one. It’s not gonna happen. But maybe if you gave them some kind of a special 442, they’d probably be really interested in doing that.” Well, the next day, practically, Hurst is up there making a presentation. And that’s how the Hurst/Olds happened.

It came out first in 1968, in silver and black, and came back in ’69 with white and gold, and then it was white and gold or black and gold ever after that. That is the story of how the Hurst/Olds first started. That got them into the custom car business.

Society: So, that episode with Hurst got you interested in limited edition cars?

JW: I was very fascinated with the custom car business, I thought limited production specialty vehicles were really a way to go as far back as the GTO and The Judge, which I really got involved with in ’69 with Pontiac.

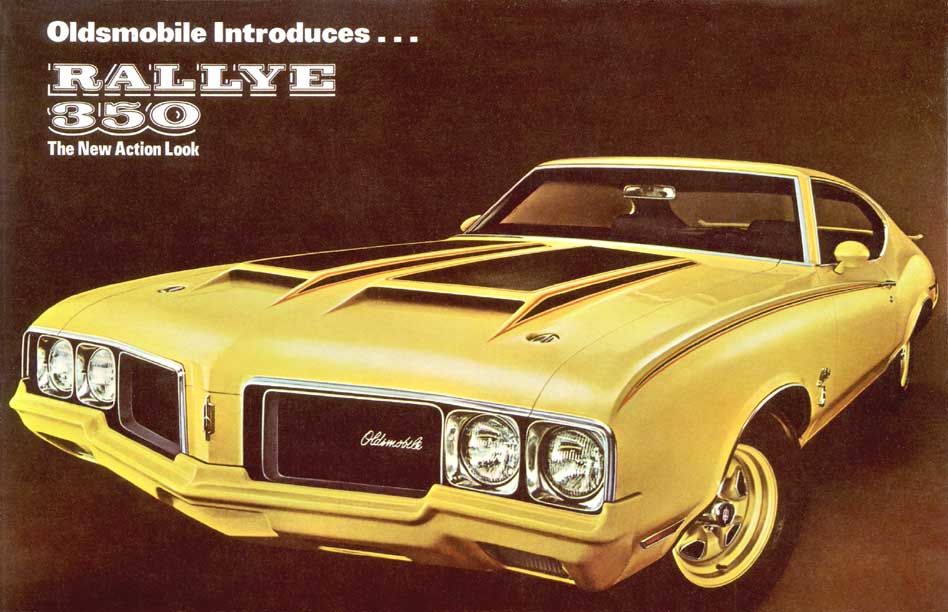

After I left the agency in ’70, and while I was fishing around trying to find myself a dealership, I took on a consulting relationship with Hurst in their specialty car division. We presented several really good packages. Remember the Rallye 350 at Oldsmobile? Well that was originally supposed to have been a Hurst/Olds. The car was put together in yellow with a kind of a purple decal package. We called the car the “California Grape.” [laughs] We presented it to them, and Oldsmobile liked the idea so well they said, “Thanks a lot, we don’t think we want to do it with Hurst.” They ended up doing it as the Rallye 350.

Society: Hurst started doing a lot of limited-run cars right around 1970.

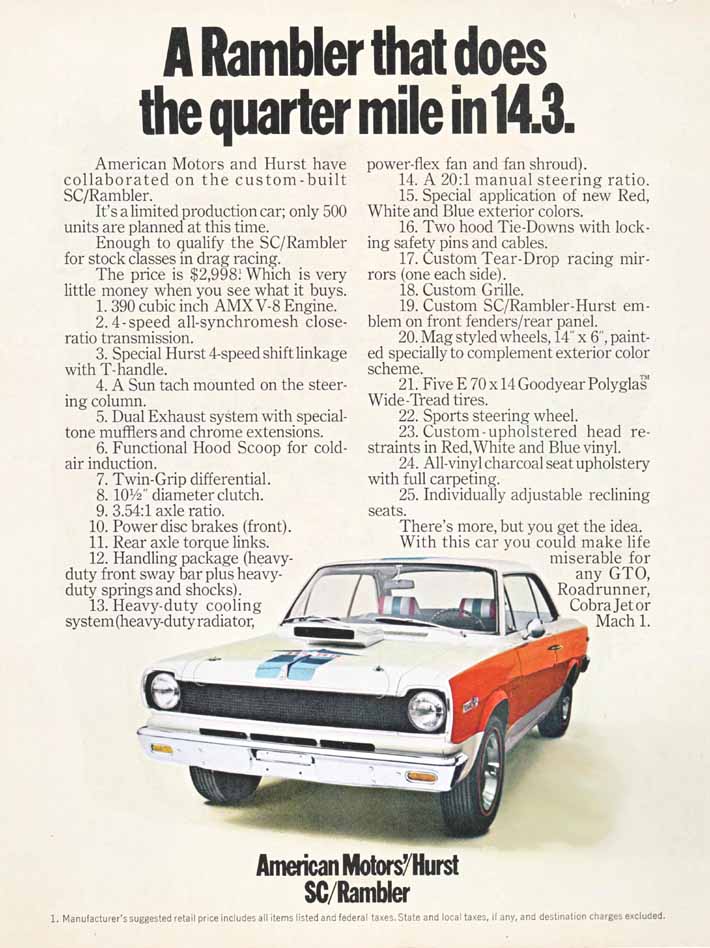

JW: Remember the 300-H, that real nice looking Chrysler that was supposed to be a letter car? That was a Hurst program that I took to them and they manifested it and sold it. Remember the mailbox, the SC/Rambler? That was a package that I got involved in. I took it to American Motors. That was a huge success, as you know. We followed it up with the Rebel Machine. Also a real nice Hurst package.

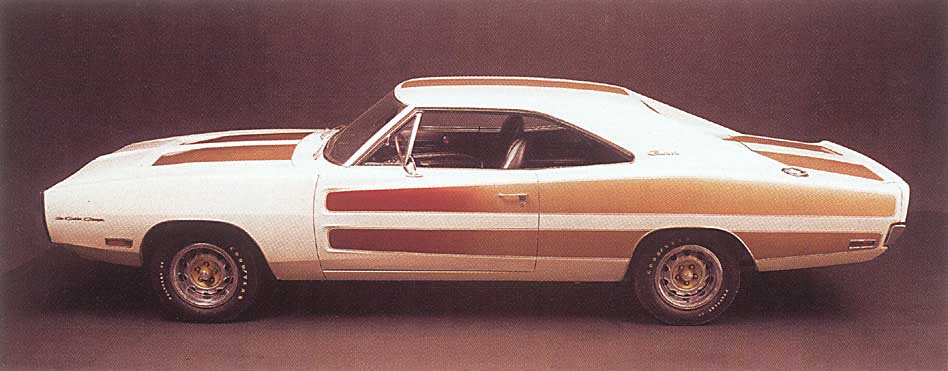

We were in the middle of putting together a gorgeous 1970 Dodge Charger package for Chrysler when I got the opportunity to go into my dealership. The dealership thing came through. So I left Hurst, but I was actually the driving force behind the car that ultimately became the Rallye 350 at Olds, that 300-H Chrysler, the SC/Rambler, the Rebel The Machine. The Charger package never came off, unfortunately. That was with Hurst when they were in the business of building special limited production cars.

I moved over to Milwaukee in December of 1970. I opened the doors of Jim Wangers Chevrolet in Milwaukee in March of ’71, right about the time they lost compression. The corporation took compression out of all the car’s engines. So here we were sitting with a bunch of low-compression Chevys after they had that fabulous 454/450 that we had in ’70. The Chevelle went to hell in ’71. We had trouble with Camaros. They were in the process of restyling it, and we had some real problems getting Camaros. Then in ’72, assembly workers went on strike at the Norwood plant. We never had any Pontiac Firebirds or Camaros through the whole ’72 model year. We didn’t get any of them. I found that I didn’t like the dealership business because I liked cars.

Society: How do you retain your interest in selling cars with all of this badly-timed chaos coming down around your head?

JW: I created a special car off the Monte Carlo called the “Milwaukee Classic,” which was kind of a neat little package. It was kind of a “pimpmobile,” but it was decent looking. It had a special radiator shell, a vinyl roof and a very nice tasteful paint stripe application. We were actually painting it rather than decaling it. We were using candy apple paint: a candy apple red, a candy apple green, and a candy apple tangerine. I ended up building about 250 of those things over a 1971 and ’72 Monte Carlo.

In ’73 we changed the Monte Carlo, I don’t know if you remember it. [I nod to the affirmative] It sure as hell didn’t need any special packages. It was such a hot package to begin with. Even though I sold the shit out of those cars and I had built a pretty damn good image for the dealership, I didn’t make any real serious money. It cost me too much to build them for what I was selling them. And I was trying to have fun. I was trying to be a marketer rather than a dealer.

I stayed in touch with DeLorean, and John was then general manager of Chevrolet. He knew exactly what I was doing. We were good friends. When the ’73 Monte Carlo was previewed to the dealers, I came over and sat through the ’73 preview.

Of course, I had worked side by side with DeLorean on the ’69 Grand Prix. I was so supportive of that car, I knew we had a winner and a half. That’s the car that really saved the Grand Prix, which was pretty much headed for oblivion after a couple of real disastrous years, in ’67 and ’68.

I sent John a telegram after I saw the ’73 Monte Carlo. I said, “You’ve done it again chief. The ’69 Grand Prix all over again.” It just struck him right. He got such a terrific kick out of that that when the Monte Carlos started arriving, I started getting Monte Carlos that I did not order. Of course, every Monte Carlo that came into the dealership was a gold mine. There were two customers for every one car. For a long time the car was so hot.

Even with my lousy management practices, we made a pretty good amount of money. It was a fairly successful operation, because you didn’t have to be a brain surgeon to make money with Chevrolet in ’71 and ’72 and ’73. I stayed over there through the ’73 model year, and going into the ’74 model year.

You might ask me, why did you go after a Chevy dealership instead of a Pontiac dealership, which was your first love?

Society: That sounds like a great question.

JW: Well, a guy by the name of Jim McDonald took over Pontiac from DeLorean. I knew McDonald, I knew him real well. He was the manufacturing guy under DeLorean for a long time before John went to Chevrolet. Jim was director of manufacturing at Chevrolet. Then he came back to Pontiac as general manager. Well Jim was a corporate guy. He didn’t know cars, didn’t like cars, and didn’t understand marketing. I knew what was coming. That was not the place I wanted to be under Jim McDonald’s direction. He proceeded to bring Pontiac to its knees, practically, by making it a very ordinary brand. He ran the corporation like so many other general managers did, without imagination, without balls, without commitment to the cars. That’s exactly what happened to Pontiac. Then after McDonald there was a guy by the name of Martin Caserio.

About 1974, McManus, John & Adams, the ad agency, had inherited from the General Motors Corporation a special multi-million dollar account introducing the catalytic converter to the world. General Motors was coming in with the catalytic converter to solve all of these emissions problems. All of these poorly tuned, leaned down engines that they were building in ’72 and ’73 and the damn cars wouldn’t run. The driveability on them was so bad when they were cold. They were trying to get the emissions in line. Suddenly they were going to solve all of that with the addition of the catalytic converter, which was going into the exhaust system.

They had given McManus this multi-million dollar task of introducing that concept. McManus sent for me when I was in Milwaukee and in my dealership. They wanted to know if I would be available to serve as a consultant for this new piece of business that they had, which was going to be a fairly lucrative account. Remember this was very early in ’74 and the converter was coming out in ’75.

Instead of taking a leave of absence from my dealership, I found a buyer for it and got out reasonably well. I made enough money to make it a positive experience. I didn’t lose a fortune on it or anything. I came back in a healthier situation than when I had left, but nowhere near what I could have or should have made.

Society: Is the dealership still there?

JW: No. What happened is that the neighborhood deteriorated pretty significantly. The dealer that bought it from me had a little trouble getting it off the ground. He sold it again to another Chevy guy, a general manager of one of the bigger stores over there. He couldn’t do anything with it. Then it became a Volkswagen dealership when Volkswagen was having some real serious problems. Now [in the early 1990s] it’s a Volvo/Jaguar dealership. They can get along all right, because it’s small; they don’t need a lot of high-powered stuff.

Society: Where was it located?

JW: It’s actually in the city of Milwaukee. It’s on the North-South Freeway at Capitol Drive, Capitol Drive and Green Bay Avenue. I ran a whole bunch of commercials where I became known as the “Great, Great Guy.” It was a radio campaign that I brought in there. My commercials always talked about [sings] “On the North-South Freeway at Capitol Drive, Jim Wangers, what a great, great guy-y-y-y. Jim Wangers Chevrolet.” Kind of a cute advertising campaign. It came out of Detroit. I had known the guy that had created the campaign. Remember the Morollis [Chevrolet] ads that ran in the Detroit market? It was just like the Morollis stuff. He was the great, great guy in Detroit.

Society: So the dealership experience has now run its course. What was your next move?

JW: I came back to Detroit and got ensconced. I had an office at McManus. I became involved with this catalytic converter thing, which was really a lot of fun and turned out to be a real interesting sort of an assignment.

One of the things that I did do, however, that goes back to right after I got back to Detroit. A good friend of mine, who had been at Hurst during the period I was consulting with them in doing limited production specialty vehicles, had left Hurst and was now on his own doing some aftermarket stuff. This was a fellow by the name of Dave Landrith. He was a pretty good guy in this limited-production, specialty car field. One day he calls me and he said, “Jim, what would you think about doin’ a special little version of the Vega, not for Chevrolet but for Pontiac? Pontiac’s having some real trouble with the Astre, particularly in the Midwest and in Detroit. It’s backing up pretty bad.”

This was in ’75. I was back in town doing this consulting work. He said, “Quite honestly, they could use some help. If we can put together kind of a little special package on this thing, we could get the job. I’ve got some pretty good contacts.” I said, “I’m reasonably contacted with the general manager.” Dave says, “Well, you don’t want to go in through the general manager with this one. You want to come in through the zone. We’ll start it out in Detroit.” Anyway, to make a long story short, I came up with a little package for him called “Li’l Widetrack.” This was an Astre with an airdam and a spoiler and a little set of wheels on it and a kind of a cute little decal. We made it personify the car like the Neon, “Hi”, you know, here was the Li’l Widetrack. It wasn’t anything new in this business.

We got the job. We put together a little facility down not too far from Lordstown where they were making Astres. We were converting these things and they got out into the dealers. They were all silver with the yellow and red and orange striping on them and had a little hood scoop. We didn’t do anything to the engine, it was just strictly an appearance package. This was in ’75, and it sold! The dealers kind of liked it. It had some special little advertising they put together for it. The next thing we know, we’re hearing from Buffalo, New York; Cleveland, Ohio; St. Louis, Missouri; Des Moines, Iowa; and they all want Li’l Widetracks for the Pontiac dealer associations in their towns. We ended up building over 8,000 of those things in 1975.

We created a little company. Here I was [laughs] working on the catalytic converter, and I had done this other thing kind of on the side. We created a little company called Motortown Corporation. We started out with this Li’l Widetrack project.

Society: What other cars was Motortown involved with?

JW: I had had a real strong feeling about what Ford had done to the Mustang in ’74. I couldn’t believe that they took that little fastback and sort of demeaned it and created that little notchback thing, which was a sort of a secretary’s car. Really a prostituted effort on what the hell the Mustang was all about. I had the idea that what they needed to do was to bring that Mustang back with a few balls in it, you know? The best engine they had was that lousy V-6 plus that four. Well, we heard that they were going to put the V-8 in it starting in the ’76 model year. So, we did a couple of renderings, and took a proposal into Ford. We had worked with a guy by the name of John Morrissey, who was at that time the director of marketing for the Ford division.

We brought in a little car called the Cobra, the Cobra II as a matter of fact, which was a nice little effort to try to bring back some of the personality of the fastback Mustangs now with the V-8 in it. You know, build some white and blue ones; some blue and white ones. We had little louvers in the windows. We had a nice hood scoop and air dam, and a nice Cobra emblem on it. It was a neat little package in its day. Well, we brought it in to this guy Morrissey. He says, “You know, you guys have got a pretty good package here, but I can’t promise you anything. Do you realize what you’re trying to do? Ford’s never done anything like this. This is ridiculous to think that we’re gonna let somebody do a car for us on the outside.” He says, “There’s one chance. I’ll do it for you guys, ’cause I believe in it, you guys are good guys, and I believe that the car’s pretty damn good. I’m gonna show it to the one guy in this company who could get this done for you. If he likes it, there’s a chance that maybe somewhere he’ll find a way to get it done.”

Well, that one guy was Edsel Ford II. So, by God, he shows the car to Edsel, and Edsel likes the car immediately. He says, “We’ve been trying to do something in the styling studio; we haven’t got it. We don’t know what we’re doing, and here these guys have done it better. We’ve got to do it. We can’t not do this.” Edsel got as enthusiastic as John Morrissey did. So he called us in. We met Edsel for the first time. He was young in those days, and full of piss and vinegar. He says, “You don’t worry, I’ll get my old man to do this. We’ll do this car. We’ll build it here in Detroit. We’re building Mustangs in Wayne. You guys get a facility together.” We had this facility together down in Lordstown to build those Li’l Widetracks, but we couldn’t build the Mustang there. We had to get a little facility in Dearborn. Well, over night this lousy little business, Motortown, is becoming a pretty serious business.

We set this little plant up down on Jonathan Street in Dearborn, and would you believe, we got this contract. They had us build a prototype. We got it done real quickly. There was a bunch of people around town that could do that stuff.

I remember when we introduced that car, at the dealer show in June of 1975, as a ’76 car, the dealers went nuts! 1976 was a very bad year for Ford. They had nothing new. The Granada was running pretty good, but they had a whole lot of losers in their line, and the Mustang, of course, was not really setting the world on fire. Here they showed the new V-8 coming, and they showed what they were going to do with the V-8. They were gonna package it in this. And the dealers stood up and applauded that car—I’ll never forget this as long as I live—for fifteen minutes! They couldn’t believe that they were gonna get a cute little car like that. So, we had put together the same kind of a deal that I had told you about that went together on the Can Am. The car generated its own ad budget. We told them that we’d probably build about 5,000 of them. You know, that would be enough to run some ads.

Do you remember Charlie’s Angels? [Yes I do!] Ford was a sponsor on that show. They saw the car and they said, “Hey! This fits our needs beautifully.” So they took and stuck it on Charlie’s Angels. One of the gals [That would be Farrah Fawcett as Jill Munroe] had a Cobra II. The next thing we know, they had 5,000 orders before they ever built the first one. The next thing we know, there’s ten thousand orders. The next thing we know there’s fifteen thousand orders. Anyway, to make another long story short, we ended up with the car generating its own advertising budget and it was in the contract that they had to spend the money in advertising. This car ended up with a 27,000-unit build, with all that money generated for advertising. So we just over advertised the shit out of this. It was running so well that Ford came to us and said, “Hey guys, we can’t let you build this many cars for us outside. You’ve done a nice job. Thanks a lot, we’re bringing it in house.” Believe it or not, that was the end of it. The car died after that. Remember they brought it out in red and white, and green and white? In the middle of the year we introduced the black and gold one to kind of commemorate the Hertz cars that they had done in the 60’s, that they had called it the GT350-H? The Cobra II was the name of the car so we called it the Cobra II-H, and sold a whole bunch of black and gold ones.

Needless to say, this lousy little company I had backed into, really as a sideline, was now producing some real, real big money. We were big-time entrepreneurs. We had taken a program to Chrysler at that time to reintroduce the Road Runner. We came back with a real cute lookin’ little package off the Volare called the Road Runner. Then we did the same thing for Dodge called the Aspen R/T. Each one of those ended up being 3,000 car builds. They packaged it around the 360, and in those cases those were pretty decent looking cars. They did pretty well with it. We had a program going on the Charger. Remember that was the year when Dodge had that real good looking car. They called it the Midnight Charger. It had a nice roof on it. We did that, and we sold 3,000 of those to Dodge.

Society: Did you have anything to do with the Super Coupe?

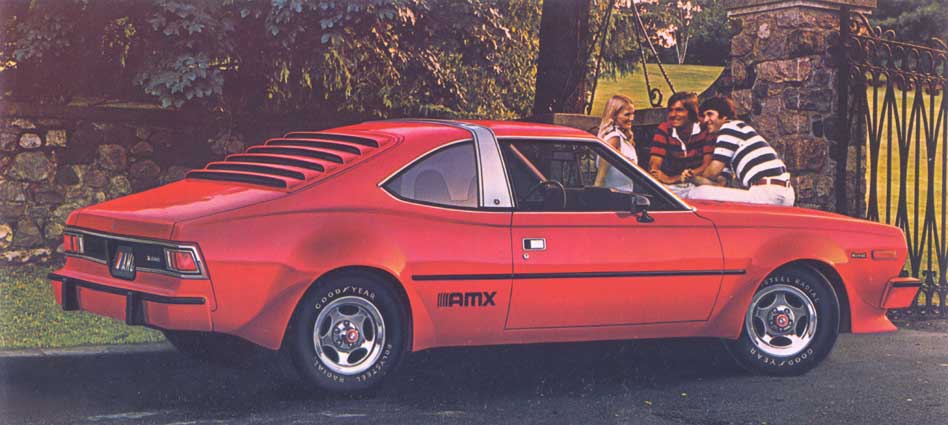

JW: We didn’t do the Super Coupe. Believe it or not, one of our competitors, a bunch of upstart young guys called Cars and Concepts came along at that same time and they got that one away from us. We didn’t submit that one. Most of the ideas that we ended up doing, were cars we submitted. We came back and did another car for American Motors, the AMX off the Hornet. That was a pretty good-looking little piece. We ended up building almost 4,000 of those.

Society: These were all built off-line by Motortown?

JW: All of these cars were built in little facilities that we had created along side the regular manufacturing plant. You see, we were right at a time when it was absolutely perfect, because the government was leaning on the corporations for emission controls, for safety controls, for mileage improvements, and they had every possible resource available, engineering-wise, tied up in doing things to keep them in business. They had no time to think about any of these limited-production specialty cars. So a company coming in with a little bit of experience and a little bit of knowledge, well of course, building that Cobra II put us right at the very front of the thing. That was a hugely successful thing. We realized, we didn’t realize in time, we realized it too late, that we had a lawsuit and a half against Ford, because they broke a contract. We were so pleased with ourselves, and had frankly made a lot of money.

We didn’t want to cause trouble, because we figured we could get some other business out of Ford, but we could have come back and just sued their ass. And it would have stood up, because they literally came in and put a little company that had brought them an idea out of business. They didn’t realize it themselves what they had done. They just flat wanted that car in house. But as I said, we were so pleased with ourselves and we were so anxious to go on doing business. By now it had become an incredible business.

END OF PART THREE

Topics discussed in Part Four:

- The 1977 Pontiac LeMans Can Am.

- End of Motortown.

- Automotive Marketing Consultants Inc., AMCI

- Charger 2.2, Giant killer.

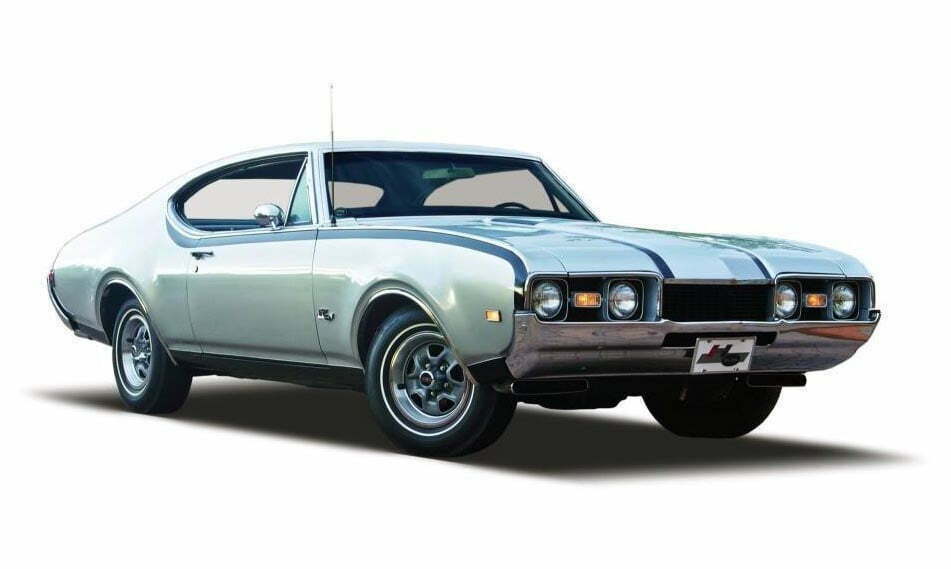

Jim Wangers Image 3-2

The program that started a great relationship between Jim Wangers and Hurst Performance the 1968 Hurst/Olds

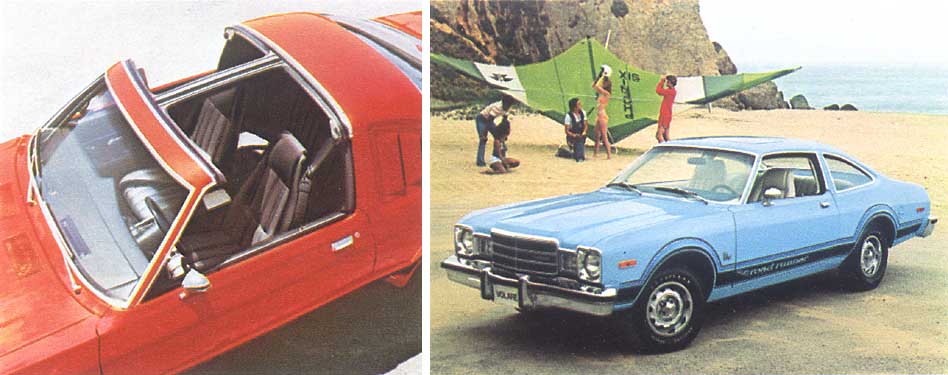

Jim Wangers Image 3-3

This package started out as a proposed Hurst/Olds foir 1970. Instead, Olds took the job in house and called it the Rallye 350.

Jim Wangers Image 3-5

If one red, white and blue specialty car was good, why not make it two? The 1970 AMC Rebel The Machine

Jim Wangers Image 3-6

One that didn’t work out, the 1970 Dodge Golden Charger. Image courtesy of Jim Wangers.

Jim Wangers Image 3-8

Here’s the car that put Jim Wangers Chevrolet on the map, the 1970 Chevrolet Monte Carlo Milwaukee Classic. Image courtesy of Jim Wangers.

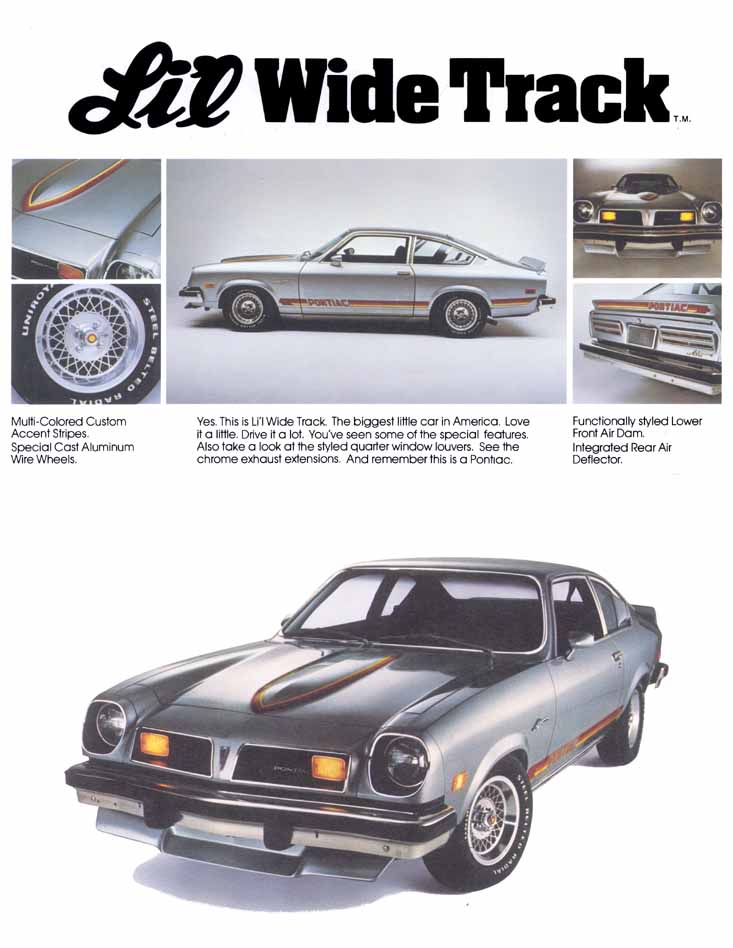

Jim Wangers Image 3-9

This is the inside spread of the 1975 Pontiac Astre Li’l Wide Track dealer sales folder.This is the inside spread of the 1975 Pontiac Astre Li’l Wide Track dealer sales folder.

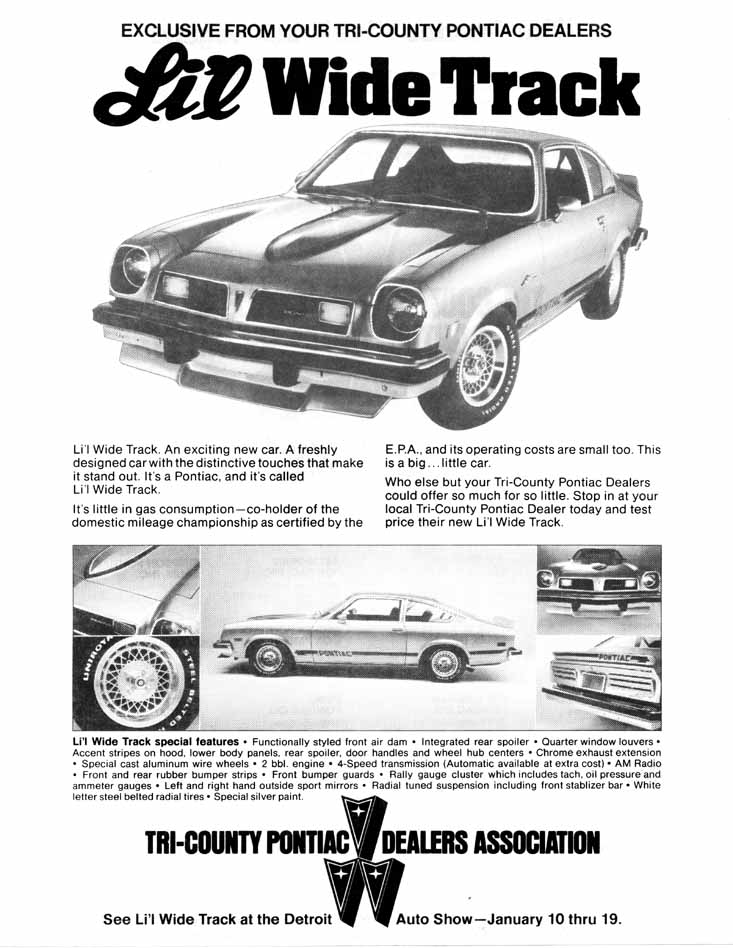

Jim Wangers Image 3-10

This is one page of a two-page ad spread for the Detroit-area Pontiac dealers.

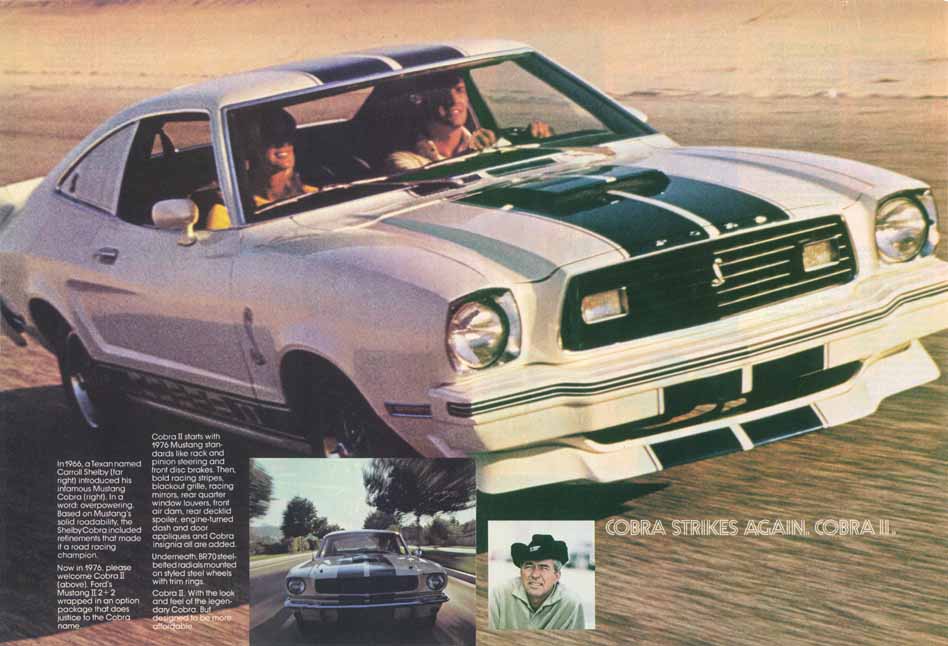

Jim Wangers Image 3-11

Hot on the heals of success with the Li’l Wide Track, Motortown puts together the Cobra II for Ford in 1976.

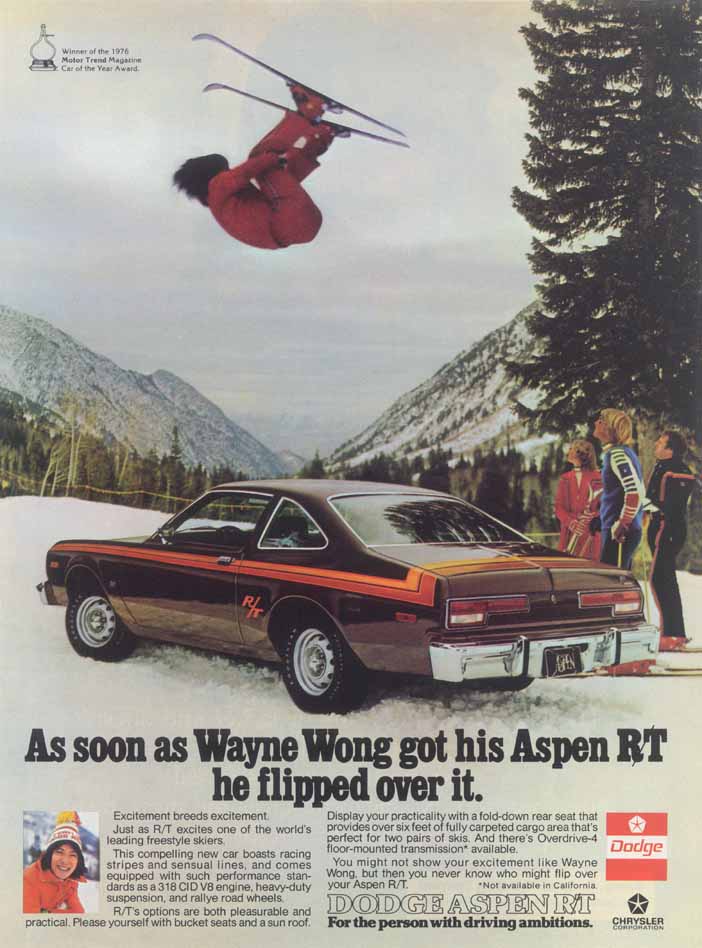

Jim Wangers Image 3-12

Also in 1976, the Dodge Aspen R/T hits the road. Motortown also excited the Volare crowd with the Road Runner package this year.