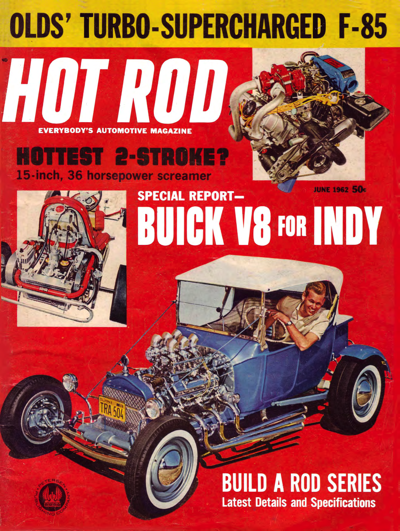

Jim Wangers Interview Part 4: Legitimizing the Comparison Test

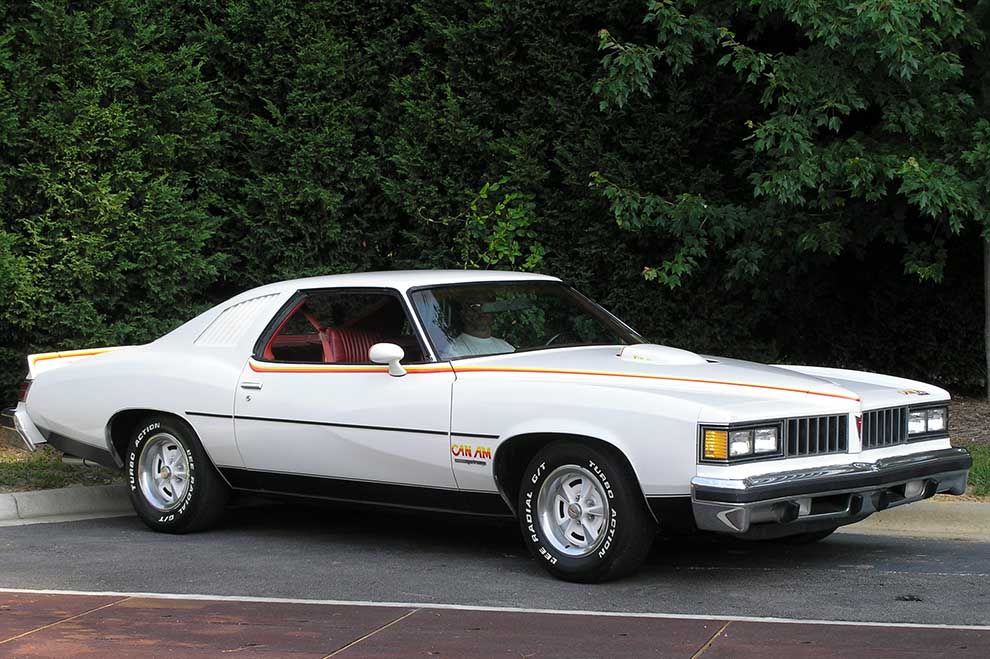

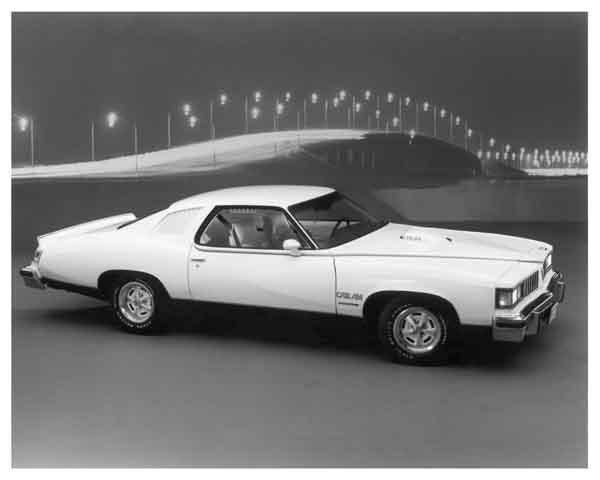

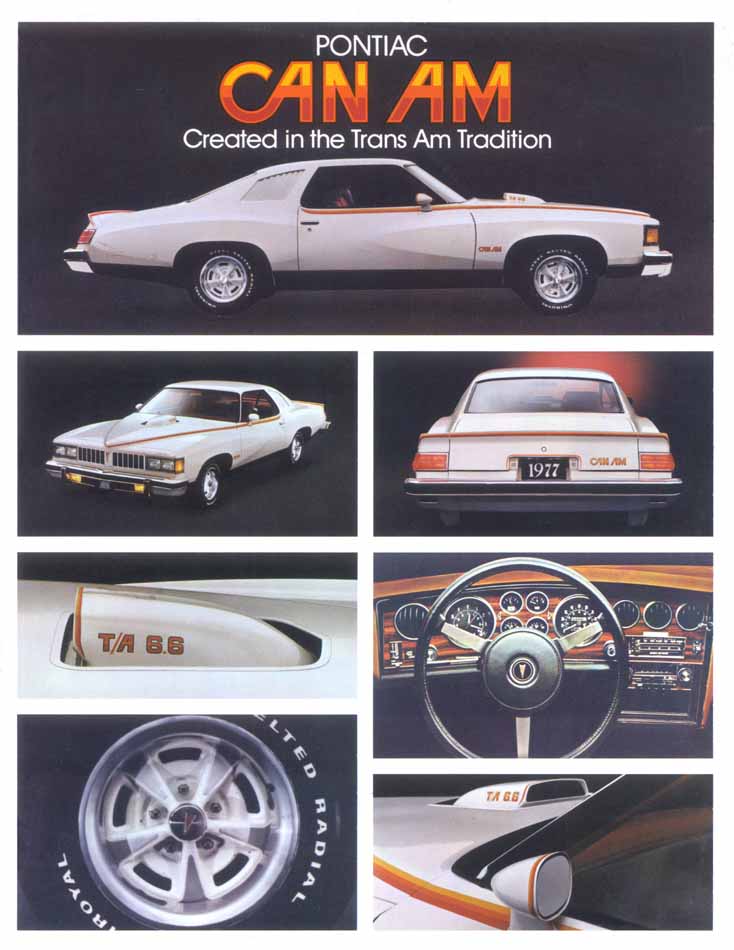

The 1977 Can Am was a hit and it gave the A-Body Pontiac back its performance image.

by Eric White, Reprint with Society permission only

Wild About Cars: How did the Pontiac LeMans Can Am project come about?

Jim Wangers: In ’76 a guy by the name of Alex Mair, who had been the director of product engineering at Chevrolet, was given the reigns of Pontiac. Before then he had been at GMC truck as general manager at GMC. Then he was promoted to general manager of Pontiac. I knew Alex reasonably well. Believe it or not, I knew his kid a little better than I knew Alex, because I had—and you’re not going to believe this—street raced with his kid.

I had a real good running Pontiac in ’70 and ’71, a Firebird, and he had a real good running–as you might appreciate–killer Chevelle. It was one of those 454/450’s. We had several good races together. We had a lot of mutual respect for each other. He had grown to understand me and recognized some of the neat things I had done. Well, believe it or not, he convinced his old man into putting me on as a consultant, if I was interested.

My relationship with Alex Mair was marginally good, but one of the things I that did with Alex was to come back and show him a really neat car that could be built off of the LeMans, which was by that time sinking into the depths of despair. The car had not done well after they restyled it back in ’73. By ’77, of course, the sumbitch was ready to almost fall off the market. So we came back with this Can Am idea, which they liked. Frankly, a guy by the name of John Schinella [Head of Pontiac 2 Studio] had done a car for Pontiac back in ’76 called the “All American” Grand Am, which had a lot of neat parts on it. They never got that off the ground, but we picked up his spoiler and we had his red, white and blue stripes that went on this car. He kind of supported it because we used a lot of his stuff. Although the idea for the car with the shaker hood and the 400 TA 6.6 engine and the 400 transmission—that was a nifty car, that Can Am. A good buy.

WAC: Do you own one now?

JW: No. Believe it or not, I haven’t found one. I just haven’t gone out after it. You know how many of them I have had go through my hands? I built every one of them.

So what I did when I got that contract from Pontiac to build that car, I finally had to own up to my ownership and involvement with Motortown. I resigned from McManus and resigned from my consulting assignment with Alex Mair, and told them that I had been offered an opportunity to go with Motortown and supervise production. That Can Am turned out to be a successful car. They were already scheduling to look at some ’78 Ideas. The ’77 car changed in ’78, it got smaller, and we had a nifty little package put together. Well, when that spoiler tool broke, Pontiac got super-pissed, and decided that they didn’t want any part of that. Of course, that killed the idea for a ’78 too, and it really erupted into some rather bad relationships for me with Pontiac. The dealers loved the car. They were ready to support the thing. That would have ended up in about a 7,000-car build, I think. That’s how fast it was headed when it finally crashed and burned.

WAC: Did you have anything to do with the Sprint Ventura?

JW: That was an aborted idea that they put together, that they thought could make it off—that car never made it into production. There were just a couple of those around.

WAC: One has surfaced in just the last year.

JW: That’s what I understand. I profess to know absolutely nothing about it, because it was never built in production. There was a couple of guys putting something together with the parts that were prototyped on it, but the car never got into production.

WAC: The Can Am lived only a short time.

JW: That was a real serious set back for us when we lost that Can Am program at Pontiac. It was in many ways our own fault. I had nothing to do with the production end. I was strictly at the marketing end of our company. We did not go out and spend enough money for the tooling on that spoiler, and we ended up trying to build it out of soft tooling, and the tooling broke. It was going to take almost ninety days to get the tooling back together, and Pontiac did not want to wait that long to ship out the rest of those cars. Much to their dealers’ dismay they canceled the program, told them they couldn’t get the car any more, and a lot of the guys were very upset, because there was some pretty good gross profit in those cars. There was guys making some serious money. Of course that got blown way out of proportion. Pontiac made it sound like we had really cost them serious money, and of course, the facts were that had they let the thing go on, there were all kinds of solutions. They could have shipped the car without the rear deck spoiler and told the customer that the spoiler was in the process of being revised; we were changing the material or something and they would get it in thirty days. The dealers would have gone along with that. Bring the car back in we’ll put the rear deck spoiler on. The only thing we were missing was the rear deck spoiler. Pontiac wanted no part of it. Unfortunately sometimes that’s where business goes.

WAC: So was this just a blip on the radar for Motortown, or was this the beginning of the end?

JW: We were really not an engineering-oriented company. We got called in, I remember, by Chrysler in the ’78 model year. They asked if we wanted to bid on building a convertible. They wanted some help from the outside on engineering, not only building it, but even engineering it. We were just not set up to do that kind of work. So we abstained from bidding while Cars & Concepts went right ahead and found themselves some serious resources and did some serious engineering development work and ended up winning that contract to build those Chrysler LeBaron convertibles. Remember the LeBaron and then the Dodge 600 convertible? That was a turnaround move for Cars & Concepts.

We thought of ourselves more as a marketing organization rather than as an engineering organization. That was a wrong decision, because as a marketing organization we really had no place to go. Ford, our biggest customer on the Cobra II, never wanted to do another dime’s worth of business with us again, because they were scared to death one of us would wake up to the fact that they had screwed us over so badly. Pontiac, which was our number two customer, was now a little bit pissed at us because we had screwed up that Can Am thing. So we were persona non grata at Pontiac at the time.

Going into the ’79 model year the industry started to get a little bit of relief from the government, so some of their own people started coming back. They got into some of the more limited production specialty vehicles. They were cutting out some of these aftermarket companies like we had established.

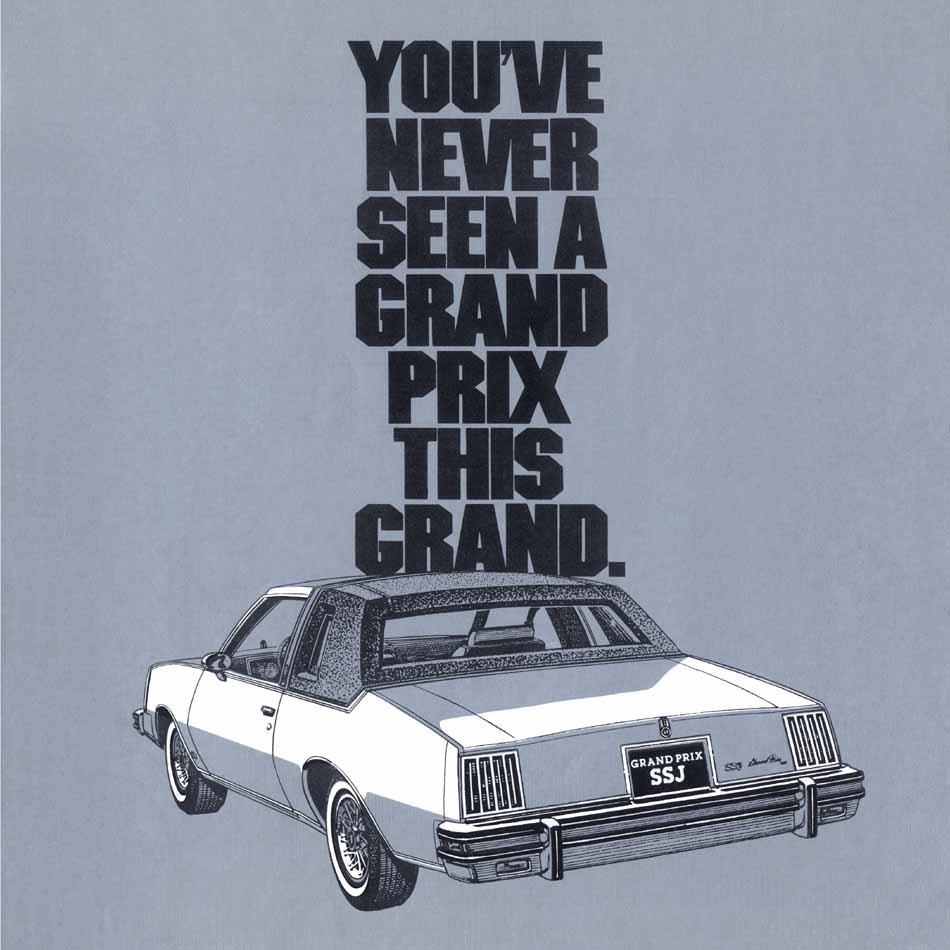

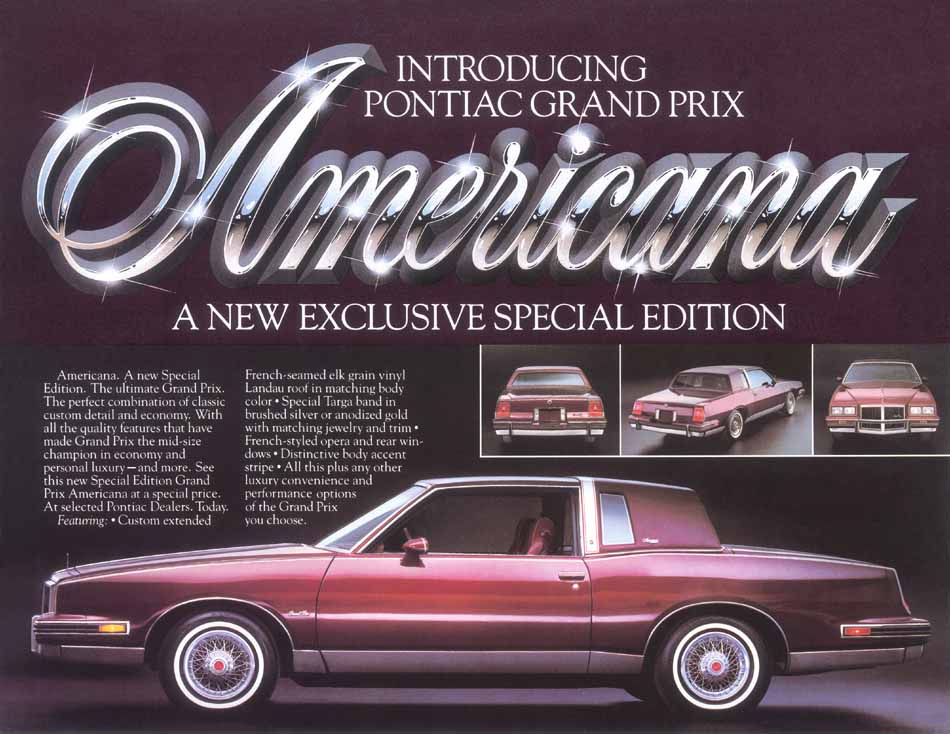

We decided to quit while we were ahead, and we ended Motortown. The last job we did at Motortown was a Grand Prix that we did for Pontiac, believe it or not. They brought out that downsized Grand Prix in ’78 and didn’t do real well with it. When it came back in ’79 we designed a roof with a targa band on it. You saw a ton of them around Detroit. We sold a big bunch of them there. Pontiac didn’t want anything to do with it, but we sold them through the dealer association. We ended up doing about 6,000 of those all told. They were done on an “interrupt ship” basis. We would get the cars; they would ship them to our facility from the Grand Prix assembly plant. We would convert it and then we would take it back to Pontiac, and they would drop ship it out to their dealers. Turned out to be a pretty successful effort.

We put together, as a matter of fact, a two thousand car build for the New York Pontiac Dealer Association. They created a special car, which they called the Americana. I never could figure out why they wanted to call it the Americana. It was a special Grand Prix. They did real well with it. They were very satisfied. They sold over two thousand of them all throughout the New York/New Jersey dealer association. They ran some pretty heavy advertising. It was a very nice package. Worked out to be a pretty nice thing. That was the last special car we did.

WAC: What was your next move?

JW: Chrysler was going through a real serious problem, if you remember, in ’79. It was right about the time they nearly went under. That’s right before they brought [Lee] Iacocca in and got themselves sort of straightened out.

Right after the Chrysler thing kind of crashed and burned, Iacocca got involved and he came back with Chrysler. The first thing he did was fire the two ad agencies that had Chrysler, Plymouth and Dodge, Young and Rubicam, and BBDO. He gave the whole account to K&E who were his buddies over at Lincoln/Mercury when he was general manager there. Well, the guy who ended up running that office was this same chap, John Morrissey, who had been at Ford with Edsel II when we brought in the Cobra II. Anyway, John liked me. He knew DeLorean and he knew my history with Pontiac.

WAC: Edsel is William Clay’s son?

JW: No, no. That’s the Ford whose dad was Henry II. William Clay is his uncle. William Clay’s got his son, Billy, who’s also a pretty bright guy. Those are the two guys that are coming along in the Ford hierarchy, and will ultimately end up, I think, running the company now that Peterson is out of the picture. Peterson didn’t like those two kids. He kept them from going onto the board, which was the dumbest move in the world. It cost him his job. You don’t take on the Ford family, I’m sorry, not if you’re working for Ford.

Anyway, the timing was just about right ’cause we brought this thing [Motortown] to an end just about the time that my good friend John Morrissey ended up with this incredible assignment. He was by now was running the office for the ad agency that had this two hundred million-dollar account with the Chrysler Corporation, to handle the introduction of the K-car, the Plymouth Reliant, and the minivan. So he sent for me. He didn’t want me to go to work for him, but what he wanted was to put me on as a consultant.

That was what really started my current company. Had I been smart enough to do it ten years earlier, I never would have gone to Milwaukee. I would have had my own consulting arrangement. I’m sure I could have put some beautiful things together with DeLorean and Chevrolet.

As it happened, after DeLorean left Chevrolet, he got in trouble with the corporation and ultimately had to resign. I don’t know whether I would have gotten involved with his company or not. I don’t think I would have ever gone to work with him with the DeLorean Motor Company, but I would have done some consulting work with him.

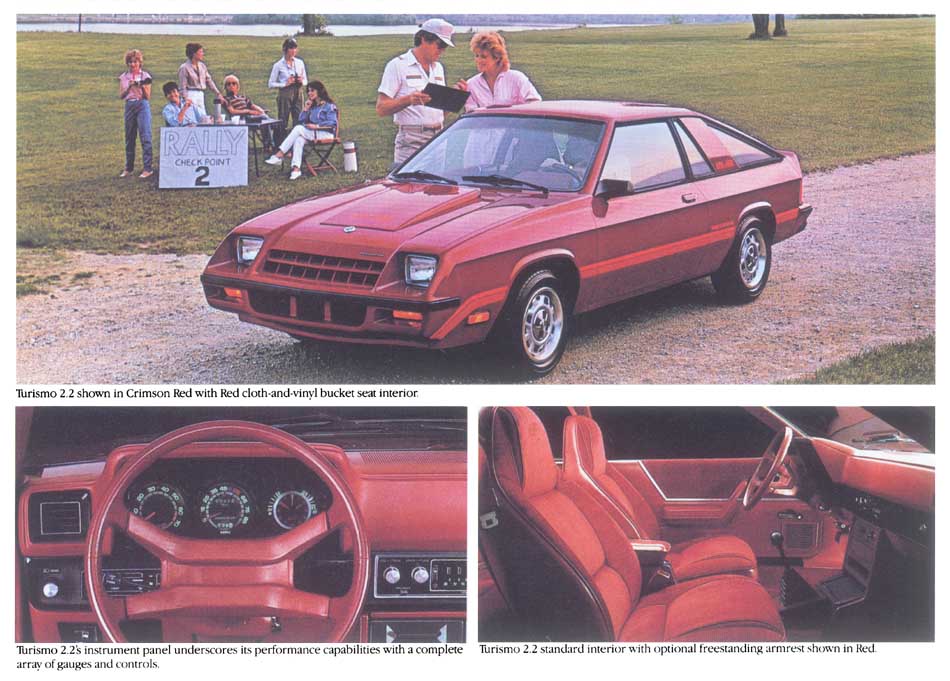

In late ’79/’80 I started Automotive Marketing Consultants, Inc. (AMCI), which was, on a consulting basis, working with John Morrisey at the New Chrysler Corporation on the introduction of the new K-car. One of the first things I got involved in was when I saw that they had developed this new 2.2 engine, and were putting it in the K-car. After they got it structured pretty well, to get it in the Reliant and Aries, they decided it would make a pretty good installation in the L- body cars, which was the 024 and the TC3, those neat little coupes they were building. They were pretty cute little cars, which up to that time had Volkswagen engines in them. Now they were gonna put that 2.2 in them. I said, “You guys have got the GTO all over again in the 1980’s idiom. You’re sticking a big engine in a little car. Don’t just waste that and put that engine in that car, put a name on it. Put some decals on it. Put some hardware on it. Bring it out as a special car.” They drifted around. I had the agency supporting me. I got an opportunity to meet Lee Iacocca on it. There were some politics, which I don’t want you to even get into. I had real problems with a guy by the name of Joe Campana, who was running the marketing end of the corporation at the time.

So I brought to them a package with, at this time, a new company called Evans Automotive, which was an outfit that had been in the custom car parts business. They had bought Motortown, or what we finally ended up dumping as Motortown. They bought some of the inventory we had. They bought the Can Am inventory. They were doing some stripes for Ford on the Cobra. I brought them the idea of doing a Charger 2.2 for Chrysler. By God, we sold that car to them.

They did exactly what I knew they were gonna—the car was a smash! Here was chance to take this cute little 2-door coupe, put a hood scoop on it and a kind of a nice configuration on the side glass. Add a little rear deck spoiler and some tasteful decals, and take that 2.2 engine, as long as you had an honest premise like the 2.2 engine, and made it into a pretty exciting little package.

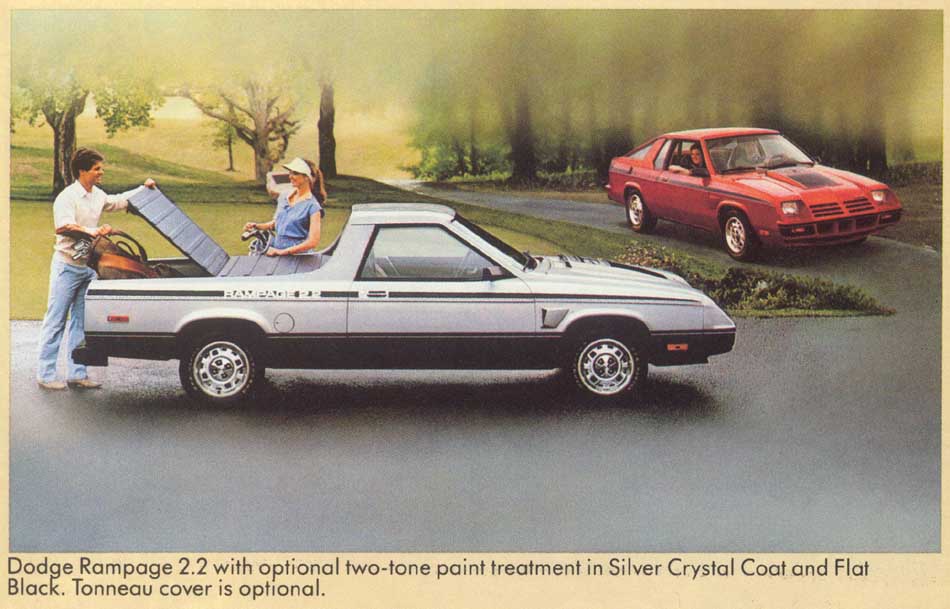

Well, they [Evans] didn’t end up building the car. Chrysler ended up building it in their Belvedere Plant, but they [Evans] ended up selling them all the special parts. By the time the parts thing got into the Charger, Plymouth’s version, the Turisimo and the little pick-up truck version, the Rampage, they ended up selling Chrysler enough parts for originally building over 60,000 units, 62,000 to be more precise. Of course, that was a beautiful parts service operation, because they had the decals. They had the spoiler. They had the hood scoop and the louvers that fit on the side. It was a very inexpensive, kind of a neat little car, and it ran pretty well.

Needless to say, that was a very satisfying experience. That was a real coup for me, because I had an opportunity to participate, again, in a build. On a percentage basis, with the parts that this company ended up selling in this bonafide, honest program, that produced some serious profit. Also, I had an opportunity, through my relationship on a consulting basis, with K&E to do some of the promotion and some of the merchandising work, along with some of the advertising on that Charger. It got a lot of aggressive advertising, because it was a pretty good little product. They sold the shit out of that thing for two years before they ended up changing it. They brought in Carroll Shelby, if you remember, and then they took the Charger and made it the Shelby Charger. By that time they were making some of their own parts, and so they didn’t care about getting anything from the outside.

WAC: How did AMCI begin?

JW: My consulting relationship with K&E turned into being a real bonanza. The thing that happened there was this. All during my period in the ’60s when I was working on the GTO and the Pontiac line, one of the things that we constantly bemoaned was the fact that we could never run any serious comparison advertising. The FTC had a ruling then that you couldn’t mention any competitors in your ads. You could not say that the GTO will out accelerate from zero-to-sixty an Olds 442 or a Plymouth Road Runner. You had to use terms like “Brand X”, which really was not a very satisfying thing. While I was at K&E on this consulting assignment, the soft drink people, Pepsi Cola and Coca Cola to be exact, and their advertising agencies, were able to overturn that ruling. The Federal Trade Commission had admitted that comparison advertising was a pretty healthy thing if it was done right. Most importantly it had to be done right. You had to make sure that you certified everything that was done. You had to have these taste tests done right in front of everybody, and you had to watch it and make sure that there was no shenanigans pulled. Anyway, to make a long story short, I thought, if this would work well for the soft drink people, why not in the automotive market? I had always wanted to get involved in doing it.

So I went down to Washington and met with the Federal Trade Commission. They had no idea how you went about comparing an automobile on acceleration or braking or cornering, but they were wide open to listening. So I put together a proposal for them, which was in effect a kind of a consulting relationship to the Federal Trade Commission, on how you would go about certifying side-by-side comparison testing for automobiles. That would allow you to be able to go on television and say my car out accelerates your car. Of course this included some very sophisticated things: how you acquire the vehicle, how you broke-in the vehicle, how you prepared the vehicle, how you drove the vehicle. Were they driven under the same conditions, the same set of circumstances weather-wise, track-wise, driver-wise? What steps you took not to have skill in there, how many runs you made that represented a full model year’s production on the car. I had had enough experience in my drag racing days and in my performance merchandising days that I was able to put together a pretty fair program for those people, which they pretty much bought, hook, line, and sinker.

I came back to Detroit—this was while I was still in a consulting relationship with Chrysler. I was able to convince them that one of the best things they could do was to take their new car line and put it out into a competitive venue as quickly as possible. One of the first cars we ended up doing it on was the introduction of the new Chrysler Laser in 1983, when they brought that pretty good lookin’ little fastback package that Hal Spurlick had been personally involved in as a design consultant, and design management.

We put that car on the line against a Porsche 944, a Mustang GT, a Camaro Z28 and a Firebird. We compared it from 0-50 rather than from 0-60, because it was right at a time when the government was pushing for that 55 mile an hour speed limit. We thought it would be very smart and very worldly for us to compare a legal 0-50 rather than the faster 0-60 and go over the speed limit.

The reason we did it, frankly, is because the sumbitch would beat those cars from 0-50, but by the time you got to 60 those other cars would come by. The reason that it would beat those cars to 50 was because they were all rear-wheel drives and this was a front-wheel drive car. With standard production tires, the front-wheel drive car got better traction, and you could literally out accelerate those guys up to fifty miles an hour. Well, it made for some pretty damn good advertising.

I’ll never forget the piéce de résistance is that Chrysler got a letter from the U.S. government, the NHTSA, thanking them and congratulating them for going from 0-50 instead of 0-60 so that they wouldn’t violate the new national speed limit. Which I thought was just a marvelous piece of justice [laughs]. But at any rate, this opened up a new trend.

One of the nicest things that happened to us was is that Chevrolet got very concerned about how the Laser could out accelerate the new Z28, especially with the new crossfire option that they had– the fuel injected set-up that they were using, throttle body fuel injection. What we had found—and this was the business we were in, we researched this thing. The Chrysler Turbo Laser was a car. It was a full entity. It was packaged as a car. It was not an optional engine. You just didn’t go down to your Chrysler dealer, order a Laser and say I’d like a turbo. You got a Chrysler Laser Turbo as a car. Well the Z28 was not marketed that way. The standard Z28 had that whimp 305 in it with a lousy 4-barrel carburetor, no fuel injection, a moderate camshaft, you know, to get the base Z28 price down. That was the car that that Laser could blow away.

Chevrolet came screaming, “Why didn’t you use our crossfire injection, that car runs like—!” They were trying desperately to build little performance overtones into that new Camaro. Of course Chrysler didn’t have to tell them, but they did. They said, “Here, take a look at the certification. We chose models. You don’t market a model, you market an option. We didn’t take any optional engines. We brought a Chrysler Laser Turbo, a Mustang GT, a Chevrolet Z28, a Porsche 944, and this is the engine and the driveline that it came with.” The reason that I go through all of this is because Chevrolet, thanks to their ad agency, Campbell-Ewald, came back to us the very next year with a big Corvette program.

END OF PART FOUR

Topics discussed in Part Five:

- The 1985 Corvette advertising campaign.

- Documenting the comparison test.

- 1990s GTO and the Muscle Car revival

- Jim’s current activities.

Jim Wangers Image 4-1

The 1977 Can Am was a hit and it gave the A-Body Pontiac back its performance image.

Jim Wangers Image 4-5

The last Motortown project was this “Americana” Pontiac. Over two thousand of them were sold throughout the New York/New Jersey dealer association.

Jim Wangers Image 4-6

A job that Motortown turned down—converting LeBaron coupes into LeBaron convertibles.

Jim Wangers Image 4-7

An ad featuring many of the special interest vehicles in the 1983 Chrysler lineup. Motortown performed the modifications to the Plymouth Turismo 2.2 and the Dodge Charger 2.2.

Jim Wangers Image 4-10

This 1984 Chrysler Laser XE advertisement featured the newly approved comparison testing with likely competitor models.