Made In Pontiac, Part 1

by Eric White, Reprint with Society permission only

Assembly Plant

In 1926, a companion automobile to the Oakland Motor Car Company’s existing product lineup was introduced. It was named the Pontiac, for the Native American tribal chief of the Ottawa people; also the name of the city in the southeastern portion of the lower peninsula of Michigan where the Oakland was built.

The immediate success of this new car was such that expanded manufacturing capacity became a necessity. In June of 1926 General Motors allocated $15 million for a new construction project. Two hundred forty-six acres adjoining the existing Oakland facility on the northern outskirts of Pontiac, MI were purchased for the expansion. The project represented the largest private U.S. construction venture of 1926, and its completion would require the use of 5,000 railroad carloads of materials.

Among the world records of the time established by this venture were the employment of the largest steel sash and cement tile roofing orders. The design of the main assembly building, which would be designated plant number eight, featured the use of large amounts of glass windows in the upper levels and skylight areas, thus the term “daylight plant” was logically linked to the new structure.

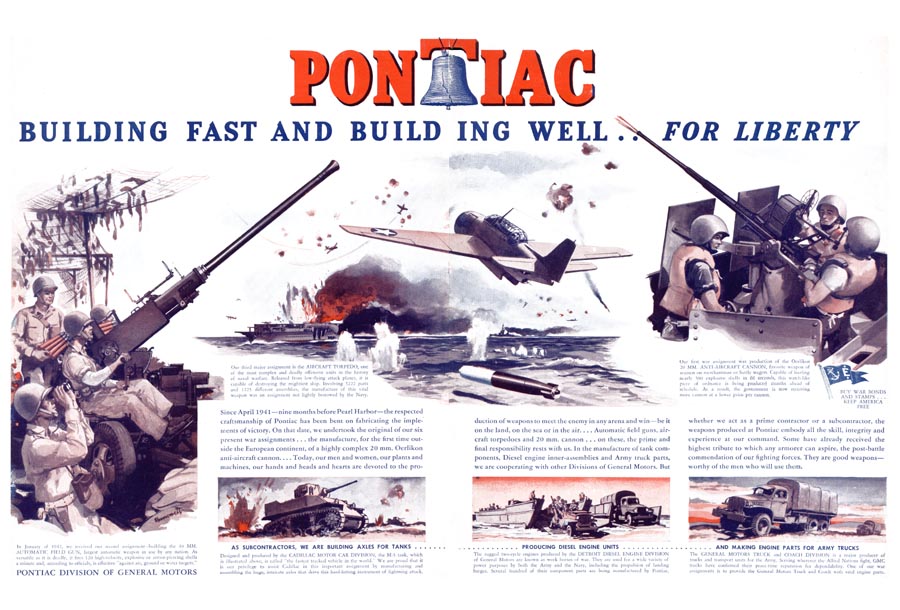

During World War Two, the Pontiac assembly complex, along with most of the American automotive industry, was converted to wartime armament and munitions production. The last civilian Pontiac passenger car assembled in 1942 rolled off the Pontiac, Michigan line on February 10th of that year. It would be 31 months before another automobile would be built in that plant.

In support of the war effort Pontiac Motors was assigned the duty of producing: the Bofors 40mm mobile field gun for the Army, the Oerlikon 20mm anti-aircraft gun used on naval vessels, aircraft-launched torpedoes, artillery shells and casings, tank axles, diesel engine parts, truck engine parts, and GMC buses for wartime civilian use. PMD earned six Navy “E” flags and two Army-Navy pennants in recognition of its outstanding wartime manufacturing efforts.

By 1967, when the 12,000,000th Pontiac was produced, a staggering sum of materials had been employed to produce that impressive number of vehicles. Among the totals were: 20,197,000 tons of steel, 3,992,000 tons of cast iron, 252,800 tons of zinc, 218,000 tons of copper and 212,000 tons of aluminum. Additionally, 14,200 tons of nickel (enough to make $90 million worth of nickel coins), 1,020,000 tons of rubber, and 55,900,000 gallons of paint were consumed in the 41-year process. The 131,000,000 square yards of upholstery material utilized over the previous four decades would cover nearly 24,550 football fields. And it would require 10,000 railroad tank cars to haul the anti-freeze used in all those Pontiacs.

By the time the last car (a Buick Regal Grand National) rolled down the Pontiac home plant assembly line in mid-December 1987 (Fieros were assembled in the nearby Fisher Body plant #17), over 26,800,000 Pontiacs had been welded, glued, and screwed together by the various General Motors Assembly Division plants. Although not all of these cars had been produced in the Pontiac plant, the largest yearly Pontiac production totals always came from this facility.

The end of line for this historic assembly plant came in the mid to late 1990s. Between 1994 and 1998 the main complex, made up of Plants two, five, six, eight, nine, eleven, fourteen, and forty-nine, were all demolished. Today a U.S. Postal Service distribution center stands approximately where the Central Foundry was located.

The Interview

A staple of most of the “big-time” muscle car magazines has always been the technical article dealing with the “correct” way to restore and detail various makes of Detroit supercars. I’ve learned that there can be more than one correct way to restore many of the parts and assemblies that make up these special automobiles. The variation of assembly line techniques, and even small differences in the parts supplied by regional vendors, makes establishing hard and fast rules regarding a common manner in which ALL vehicles are bolted together virtually impossible.

Even documenting the “correct” way to restore a Corvette, which was built at one location each year, is complicated by the running changes that are implemented throughout the model year. Multiply those changes by the six plants that assembled the 1968 and ’69 Pontiac A-bodies, and we can easily conclude that one size does not fit all.

Through the process of inspecting and disassembling original untouched cars, poking around salvage yards and listening to friends relate similar stories; I have learned never to say never on matters dealing with this subject.

One line of investigation I decided to pursue was to actually sit down with someone who had worked in an assembly plant where Pontiacs were built. As fate would have it, my father had worked with just such an individual for over twenty years. Both my dad and Mr. Carl Papke worked for Detroit Edison on line crews operating out of the Bad Axe, Michigan warehouse. Carl is a gregarious individual who enjoys talking about his experiences on the assembly line in Pontiac. Carl also enjoys owning, restoring, and driving the Ponitacs he helped to build in the mid to late ’60s. I was able to sit down and get some of his recollections recorded onto tape.

The following interview was conducted at the home of Mr. Papke on December 28,1991.

The information recalled in this interview is as correct as twenty-eight year old memories can be, and should be viewed in that light. Also, keep in mind that these observations relate only to experiences occurring in the Pontiac assembly plant during the course of one of up to three daily work shifts.

Wild About Cars: Give us some of your background.

Carl Papke: Well, I grew up in Clifford, Michigan, and graduated out of Kingston high school in 1963.

WAC: Where is Kingston?

CP: The thumb area of Michigan. Sixty miles north of Pontiac.

WAC: Were you always into Pontiacs?

CP: When I was a kid in high school I liked Dodges, because ’62 Dodges were the state police cars. They were already starting to get a reputation. I don’t remember knowing about ’62 421 Pontiacs at the time. I knew about state police cars. I wasn’t aware of Pontiacs until I was seventeen years old. I got into a ’63 421 Super Duty Catalina that was owned by a guy by the name of Joe Fercowitz. He’s dead now. He got killed in that car. Right over here west of Silverwood. Went off the road doin’ over a hundred miles an hour and it killed him. His brother John still runs the farm over there.

But Joe gave me a ride in his Super Duty Pontiac. The most God-awful thing I ever rode in my life. We went north out of Clifford goin’ out towards the power plant. There was a substation out there, it was probably a quarter mile flat stretch, and we were well up to a hundred miles an hour and stoppin’ by the time we got down on the corner, which was a half a mile. That thing had tri-power on it, it was just screamin’ and haulin’ ass. It was a real car. I never thought about Dodges again after that.

WAC: What’s that area of the state like?

CP: Just farmland. A few machine shops. The trailer-home factories of Marlette are just six miles away. At that time Marlette was the trailer factory center of the world. If you went over there and went to work in one of those factories, you knew somebody in there. Your dad worked there; your brother worked there; somebody always had somebody to get in. My older sister and her husband worked there, but that wasn’t for me. I couldn’t go to work anyway, because when I graduated in June I was only seventeen. I had to wait until I was eighteen. So, I went out to Deerwood, Minnesota and worked out there building cottages on a lake shore.

WAC: What part of Minnesota is that?

CP: Near Brainerd, in the central part of the state. Before long I turned around and came back from there. The friend that I had gone out there with, his grandma and grandpa lived there, he got drafted into the army. That’s when Viet Nam was first getting started. I rode a bus from there back to Imlay City, Michigan.

I had had my eighteenth birthday when I lived in Minnesota, so when I got back home I took a few days to sit around and think about what I wanted to do. The car plants was the supreme place to go and work at that time. If you wanted to make big bucks you went to the car plants. So, I went down to Pontiac Motor.

WAC: Did you know anyone there?

CP: Nope. Never knew anybody down there. I just knew the people around Clifford. There was a lot of the guys that had families, and they worked down there. I went to the employment office. It was on a Friday afternoon, and I started work on Monday morning. It was just that easy. You went in there and they gave you your physical right there. When I went down, I knew the stuff I needed to have with me. At that time it was standard procedure; all you had to have was a high school education. I had my diploma with me when I went. I hired in on days, which was unusual. But they hired, at that time, basically everybody in on days.

WAC: What time of the year was this?

CP: October third, right after changeover. They were building the ’64 model Pontiacs, but it was still October ’63. Production was up, at that time I’m thinking, 30 cars an hour. Normal was 70, and they were just coming back. They were building up speed all the time. I went into the plant. They gave me a clock to go to and a foreman to report to by the name of “Tiny” VanKonen. Tiny was his nickname. I couldn’t even tell you his first name. He was a great big guy; a four hundred pounder. I got along well with him because his sister lived in the same town I grew up in, which was Clifford. I grew up with her sons. So me and this general foreman – he wasn’t a line foreman, he was a general foreman – we got along real well right off the bat.

WAC: What did they have you doing at first?

CP: They had me putting in headlights. Driver’s side headlights. You had a little carpenter’s apron that held chrome screws, and a little bitty air wrench that had a flexible hose. You carried it with you. At that time it was dual headlights, so you took two headlights with you. One held against your chest with your arm, and the other you carried in the same hand. You reached in and got the plugs, plugged it in, put it in, couple of little screws went in, and you installed the chrome piece that held it on. That was my job. After a half a day, hell, you could knock ’em right out; you were just goin’ to town. It kept you busy for the first three or four days, and then you got used to it. Then you could just put headlights in and talk and look and gop. You could look at every car engine that come down the line. Being a kid, I was interested in everything that had tri-power on it. I was lookin at it and lookin’ through the windows at it, and I wanted one so bad I could taste it. I worked on that job for at least a few months.

WAC: Did they start to cross train you on different jobs on the line?

CP: No. That was my job. Putting headlights in. The first thing that happened to me was I got bumped onto nights. I think I worked there for thirty days before they could bump me off days onto nights. There was a time limit. Then when I got bumped onto nights-somebody on afternoons wanted to come on days-that’s when I got my job changed.

I went from there to the bumper line. On the front bumpers of the big cars there was a steel bracket and bumper brackets, and I’d assemble that and tighten it down. Then on the Tempest, on the rear bumpers only, I’d just put back-up lights into it. It was just a little metal clip and two screws, tighten it down with a small air gun and you were on your way.

WAC: What was your hourly rate?

CP: I think $2.73 was what I started out at. I moved to Pontiac and stayed in a boarding house. A house with an old man and an old woman. Seven dollars a week was what I paid for room and board. I would walk from there to the only McDonald’s restaurant in Pontiac at that time. There wasn’t any north of Pontiac then. There wasn’t a McDonald’s in Flint or Lapeer, no place like that. For 73¢ every night I could order two hamburgers, a chocolate shake and an order of french fries. That was my supper. I could live on seven dollars a week that way. I’d pay my seven dollars room and board, and I could save seventy-five dollars a week.

WAC: After the bumper line, where did you work?

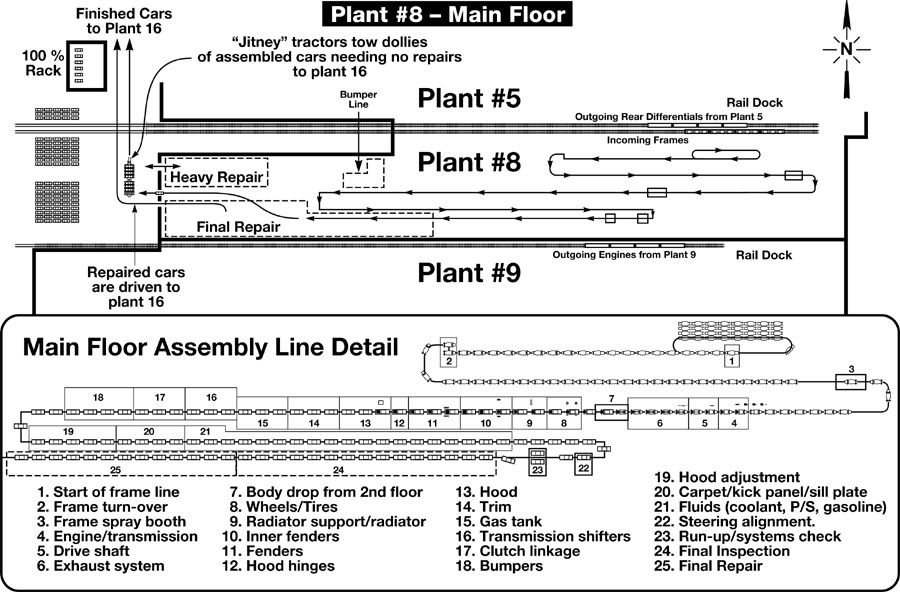

CP: I went into a place called “the pits” where the car is moving over the top of your head on the assembly line. I didn’t stay there but a short time when I went to the frame line, which is right at the beginning of the assembly plant. They had a rail dock that came right in beside that with train carloads of frames. They’d come in stacked fifteen, twenty high.

There was a guy there, he would look at the manifest and determine what car was going to be built. If it called for a ’64 Catalina convertible, he would get that frame and put it on the line. At the same time that was happening, on different floors of that plant, every place at that same time, the fenders were being built for that car, the motor was coming out of Plant 9, the rear end was coming out of Plant 5, and they were all going to meet approximately forty-five minutes later.

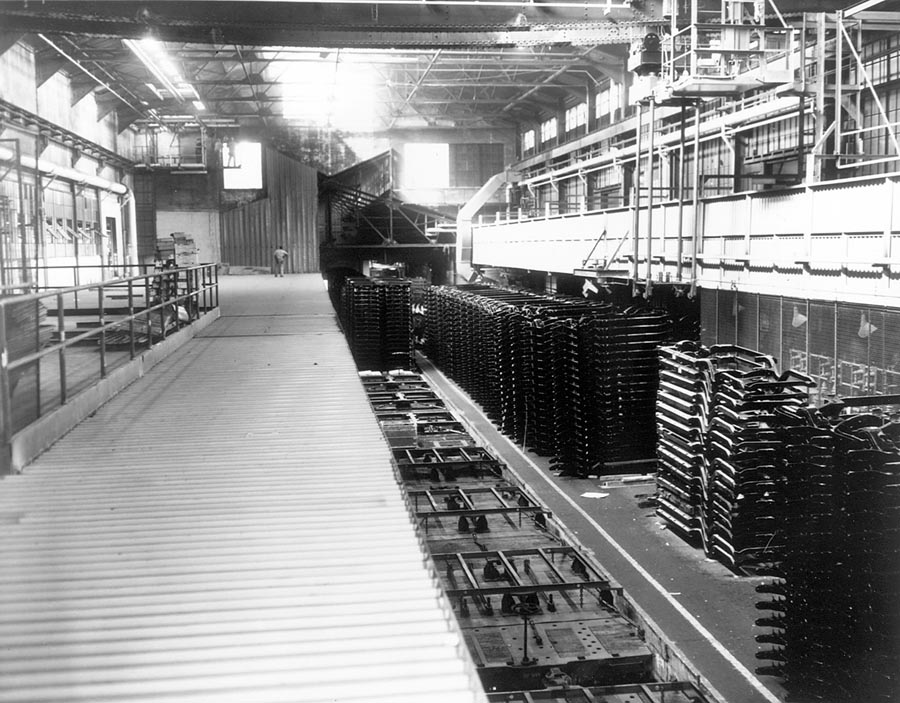

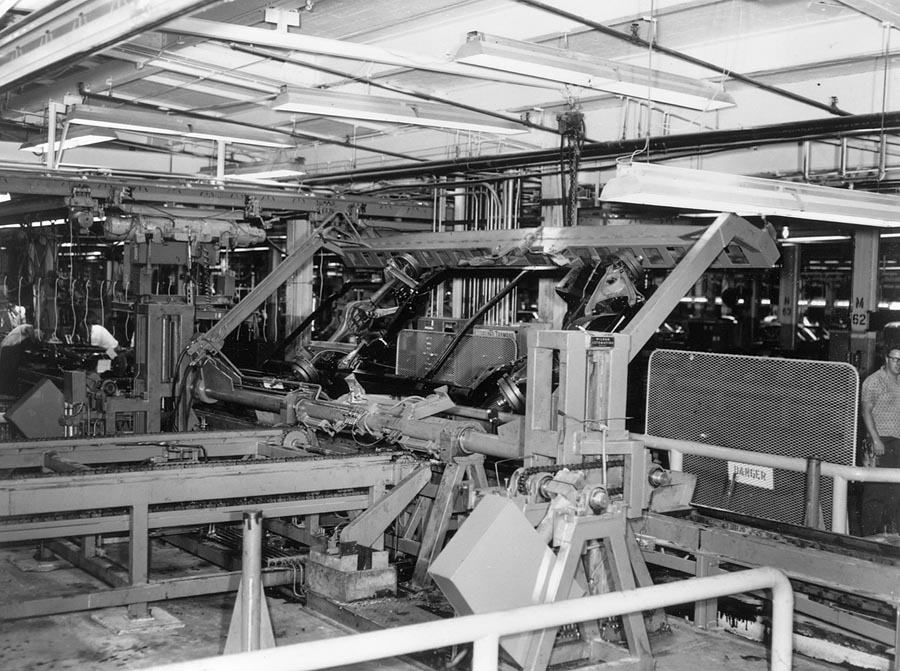

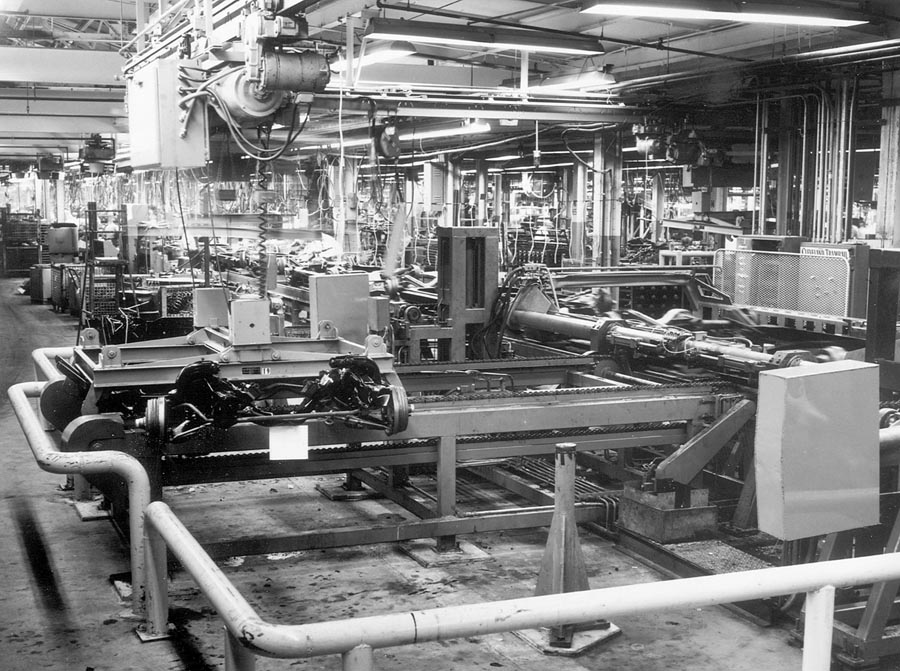

The frame would go down through a group of workers on both sides. That line was probably sixty yards long. By the time it had traveled down through there it had picked up gas lines, brake lines, shocks, A-frames, sway bar, some small clips and brackets. Then it would hit what they called the frame turnover. It would turn over in a big machine that was all automated. Nobody ran that. That machine would turn it over, set it right back down in perfect rhythm, and it would be coming back the other way.

Now they would be puttin’ on the hubs, springs; they would be puttin’ mufflers under this thing, exhaust pipes, and the brackets would be held onto it. By this time it had come back down the 60 yards. At the end of that 60 yards there was a spray booth, and they would just slobber paint on this frame. It wasn’t painted in any special fashion.

WAC: Up until then the frame was the only thing painted?

CP: The frame itself was already painted. It was previously painted like 70% gloss black. It seems to me, I remember those sway bars came painted black. I don’t remember those bars being made there. They were shipped in. They were painted a shinier black. It was a thin watery black. It wasn’t a quality paint, just something to protect ’em. But then I seen skids of them come in that was all rusty too. If the suppliers got short on paint, and they couldn’t put paint on ‘em, then had to set them outside, they rusted.

Two cars could come out and one could have a painted one, one would have a rusty one. They were both right. Just depended on what the supplier did. There was a lot of parts that got put on cars that looked a long ways from being new. Tie rod ends and center links were all bare metal. I don’t remember them being painted, but I never put them on. Different things like that were what got painted with that black goop. The parts you were putting on – the shocks were gray, the brackets to hold the sway bars weren’t painted. They were all just shiny metal. The rear end housings were completely clean, no paint on them.

WAC: They came from another plant?

CP: Yeah. They would come over on a line. They’d come through a hole in the wall from Plant 5, which was to the north. They would assemble them rear ends over there. They’d put the brake drums and everything on over there, so when we got it, we got a complete third member.

WAC: How did you identify them?

CP: They had a sticker on ’em. The Tempests had them on the end of the axle, right in the center of the brake drum. They also had letters stamped onto the carrier tubes.

WAC: But you didn’t really stop and read those.

CP: No. They were color-coded. Pink meant roughly 3.55. Blue meant something else. You looked at your manifest, and you looked up there and that rear end was right.

WAC: Where was that color splotch located on the differential housing?

CP: I want to say on the pig itself. On the top.

WAC: On the pinion end?

CP: Right on the top of the carrier itself. I don’t remember all of the colors. I remember pink. It seemed like everything that they used was odd. Not all of them colors related to us. They might relate to production assembly over at plant 5. That pink carrier meant this, a green carrier meant something else. By the time it got to the assembly line, it might not have meant anything to us.

What meant something to us was that red sticker code on the end of the axle. That was the sticker we looked for. When you put that rear end in there, the line that the frame was sitting on had a pair of steel pinions sticking up. They’d set that rear end there and it was the right height for the shocks to be hooked up; the right height for the carriers to be hooked up, and the springs were setting in there. They were already bolted in on the top and the bottoms. They would put that rear end in there and it would set on there, and the carriers and the shocks would hold that all together. They’d roll it over and it was just there.

The springs had tags on them. I remember a little tag that was around the center of the coil, and it had a number like YZ, XH, I don’t remember the numbers, because this has been more than twenty years ago. I remember the shocks had tags on them too.

WAC: These were the spiral type shocks.

CP: Yes, the flat gray spiral shocks. It had another tag. It didn’t have any thing to do with the tag on the end of the axle. It just said what particular type of shock that was.

WAC: And that corresponded to the build sheet?

CP: If the guy had ordered a handling package or a trailering package, or whatever they called it at that time, and it called for a YZ shock, the guy on the line automatically put YZ shocks on.

WAC: How many build sheets came with each car?

CP: There was one on everything. When a rear end came in, it had a tag on it, but it also had a build sheet on it. The frame had a build sheet on it. Any of the large components had build sheets. Basically there was only two on the frame and the rear axle until it got out on the main line.

WAC: The frame was placed on the line right side up, traveled down the line one way, turned over, and came back on another parallel line the same distance. What happened after that?

CP: It would go through the spray booth and they’d drizzle this black paint, I called it half tar and half thinner, they’d drizzle that stuff all over it, and then they’d turn it over and it’d be setting the right way up and be heading towards the back end of Plant 8. At that point, they were approximately thirty car lengths from the body drop.

This was where things started to happen and this frame started to come together and they were putting on the fine stuff. As it went up through there they were adding things like the steering gear boxes which were all paint coded. And each one of them had a manifest tag on them. Them guys, they’d grab a steering gear box and walk over to the frame.

The first thing they did, it was automatic, they’d just rip that manifest off and usually they’d wad them up and throw them at a fifty-five gallon drum sitting there. The custodians and sweepers would keep that area cleaned up, and they’d keep that drum empty. They would go through like two drums a day. Just before the body drop the motor and transmission would come down off the second floor together. It would have manifests on it. They would set that whole rig right into the frame.

By then the transmission crossmember had been put in and tightened down. They would do this in a period of ten to twelve feet on the line. One guy on each side of the line would be putting in a single motor mount bolt. It would go directly from there in under the body drop. This was a huge hole in the second floor.

The body would come down in like a giant claw that clamped over the top of the body, and it would set them onto the frame. There would be like four guys in the pit, one on each corner. Each one would have a steel spud wrench. As the body would come down, they’d have that sticking up through the hole in the frame. They’d have one hand on the body, and they’d stick that spud wrench right into the pre-threaded welded hole in the body.

They’d lower that body right down on there, pull the wrench out, put a bolt right into an air wrench, and put that bolt in with the wrench. Now, many of them bolts were cross-threaded, but the air wrench had enough power that it’d pull ’em and tighten ’em down. It didn’t matter if they were straight or not, because nobody anticipated taking them back out. If it went in cross-threaded that wrench forced it in all the way. And if it went in straight, that was fine too.

Topics discussed in Part Two:

- The assembly process continued- the body drop.

- Pontiac Assembly campus layout.

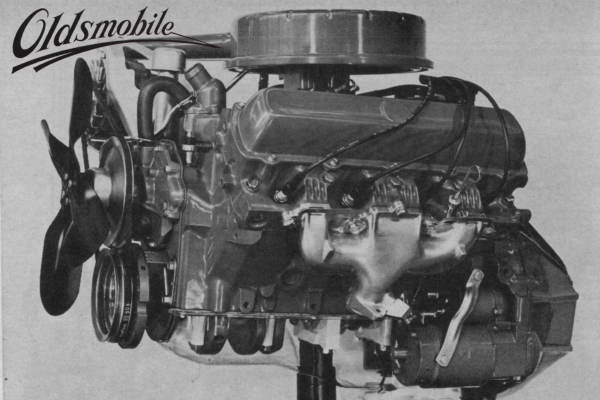

- Building engines in Plant 9.

- Racing a Royal Bobcat GTO.

- Ordering a 1964 GTO.

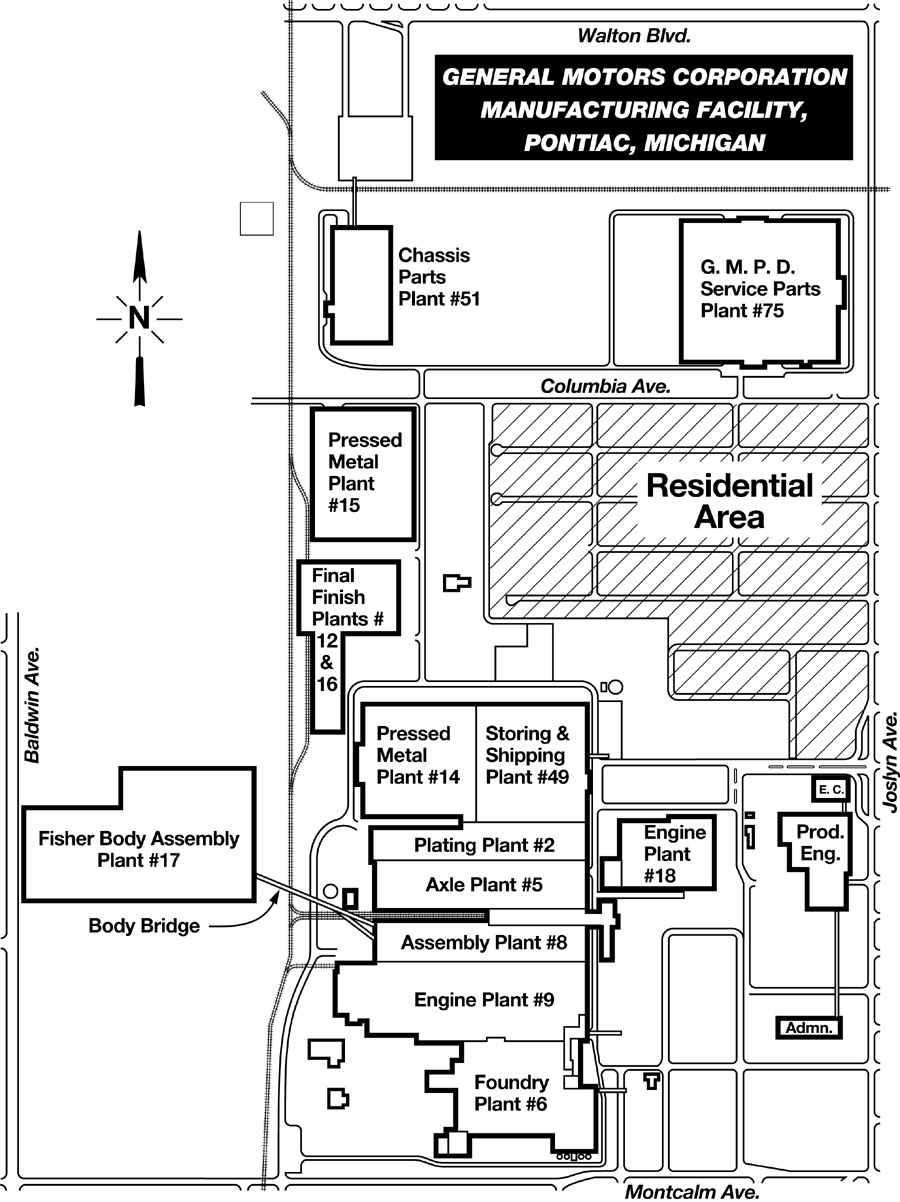

Plant layout of GM’s Pontiac Motor Division

Plant layout of GM’s Pontiac Motor Division home assembly complex located in Pontiac, Michigan . Circa 1969.

Made in Pontiac Image 2

Life magazine ad touting Pontiac’s “aquatic” contribution to the WWII war effort.

Made in Pontiac Image 12

Frames reach the end of the suspension line. Frames flip from one line to the next. Note bare metal components on frame assembly.

Made in Pontiac14

As frames are laid back down, they head back up a parallel line where brake and fuel lines are installed.