Made In Pontiac, Part 5

by Eric White, Reprint with Society permission only

WAC: What about the sequence number stamped on the front of the block?

Carl Papke: The sequence number on the front of the block was good if everything was perfect. If something was wrong, it was just out of line. They had different places on the frames that they would stamp. There was a guy that would stamp a sequence number on the driver’s side rear frame rail. Well maybe that frame had gotten mixed up in the frame turnover and was bent. They would change the frame on that car

It was not an unusual thing to see two guys changing a frame. I mean, it wasn’t an everyday thing, but it wasn’t unusual either. Naturally them numbers aren’t going to match.

This numbers-matching on a motor doesn’t mean a whole lot to me, because I worked in a plant and I saw how stuff was coming out. When you build eighty-one cars an hour for eight hours a shift – without a calculator I can’t tell you how many that is – but I can tell you one thing, if the guy went out and had three beers for noon and he come back and he miss-stamps something, chances are he didn’t care enough about it right then to re-stamp it. Chances are the inspector wasn’t looking for the stamp either. He wasn’t looking to see if the stamp was right. He was looking to see if this was put on right, if that bolt was tight. He didn’t care primarily about them numbers.

I tell you one thing, in the factory you couldn’t get your hands on the rivets used to hold the V.I.N. tags on the body. There was one guy that was responsible for them rivets. If he put three tags on, he had to use six rivets. He turned his rivets in. I looked for rivets before, and they weren’t around.

The hinge and spring were put on separately. The spring was put on after the hood and hinge was assembled to the fender. It was put on with a tool that looked like a tire iron. That guy would walk over there with that spring, stick it on and put that tool in and pop that spring on. One guy would open that hood up and two guys would walk up on each side and pop those springs on. I do remember the hinge being dark. Maybe something like a black phosphate with oil coating.

The hoods and fenders and grilles, valances and other little pieces were painted in Plant 8. There’d be like four guys in the spray booth standin’ side by side. The fenders would come through, then the hood would come through, then the other pieces. Every third or fourth piece was that guy’s piece to paint. He maybe painted all the right hand fenders. As the hood come through, he didn’t spray that. The fenders would come through side by side. They’d be hangin’ on a fixture off a track in the ceiling. One guy here and one across, and they’d both be paintin’ them fenders right together. The hoods would ride flat right behind the fenders.

When an order for special paint come through, the utility man for that area would have like a five gallon drum for each one of those colors. He would go and make sure that each one of them had the air machine to stir ’em and that they were stirred up and that the air hose was hooked up. He’d tell the painters that this was a special color comin’ through. You might have two or three special paint orders come through a night.

The common colors was coming right out of the wall. Them guys was standing on grates in there. Water ran down a big wall of sheet metal behind them and under their feet. As soon as the parts left the spray booth, they went into what they called the paint ovens. It was all heated by lights.

That place was spotless. Every night they rubbed that oven all down with oil cloths and big dust mops. If you went in there, you didn’t go in there with your bare shoes on, you went and tied white bags on your feet before you went in there. They were real particular and fussy about that.

If you watched them painting cars, you wondered how they could get them so smooth, because they weren’t experienced painters. At least not at first. They would take a guy in there and teach him how to paint. Two hours latter he was painting. A kid that had never picked up a spray gun in his life, and two hours later he was painting.

When you did mess up, they had a repair area. A guy that would wet sand the bad piece and re-spray them over if you got a run in it.

The set-up they had wasn’t complicated, but Lee can’t paint a car today, and he sprayed in the booth for two years. He wouldn’t even consider trying to paint a car today. He wouldn’t know where to start. You didn’t have to mix nothin’. You didn’t have to do anything but hold the gun, go this speed and pull the trigger. Make sure you’re overlapin’ it right.

From the spray booth the parts went through an oven. It used banks of lights. Those lights were hot and they’d flow right out and you’d have good paint when they came out the other end.

You used to see a lot of guys with lunch boxes painted Iris Mist. Their shop carts, toolboxes had RAM AIR IV on ’em. All your skilled trades always walked around with a cart, and they’d have GTO emblems on them carts. They fancied them things up to suit their own tastes. The next guy might have just a plain old red one that was all scratched up. He didn’t want nothin’ on his.

I don’t remember the first ’65s having pinstripes on ’em. That pinstripe didn’t start right in the beginning. It might have started in like November.

When they started out they were putting it on with just a little hand held rig. They’d screw a tube of paint into a deal that forced the paint onto a felt roller. The faster they went, the nicer it turned out. You’d see them guys walk up there, and they’d set that down, adjust it, and just walk down the length of the car. One guy on each side of the car.

I only remember them doing a few of them that way. There were too many smudges, blotches, runs, rolls, and too much dust in Plant 8. They moved it out of there and we never saw it again. They were doing that someplace else. Probably in 16. Plant 16 was a real clean dust-free plant.

I heard guys just windin’ those big Pontiacs. You could see the speedometer run up as high as 80 mph. Then they’d be backing ’em off, and they’d be squealing the brakes. Especially if they were a little bit behind, they wanted to get it rolling up to sixty and back down. They were checking the lights checking the horn and getting it off before the next one came up. They had to get their quota of cars done. You had to keep up with the production line.

Down in the back end after they came off final repair is where them guys would hit beams. It was close quarters. If they scratched ’em up, then they shipped them out to the body shop. They fixed them over there. They used bondo in ’em. They repainted them and touched them up. If it was a door, they would just change the door. If it was a hood, if it could be repaired, they’d repair it. If not, they changed the hood. If it was a front fender, they’d change it. If it was a quarter panel they bondoed it. Not any different than any other body shop. They had like ten guys there, and that’s all they did was repair that kind of stuff. You’d get people tearin’ around back there, they’d back into each other, and on wet roads they’d slide into each other.; a lot more accidents than the average person would think.

If you got a new car and you could detect a difference in the paint, you’d better have looked it over real closely, because you might have a quarter panel full of bondo, and you haven’t even gotten started driving that GTO yet. Today you might say, “Well somebody else did this,” yep, they might have. Twenty-five years ago it might have been done right in the factory. It kept ten or so guys busy.

I did see bodies slip out of the cradle. The machine that picked the body off the dolly would go right down over the top of the car. Then it would come in and it was adjusted to just touch the car. It would have carpeting wrapped around the forks. It would then pick it up, and as it picked it up it would put more pressure on it. I saw cars setting crooked on the dolly. The machine would pick them up and it would be half way over the body drop and suddenly slip down. One side would be where it was supposed to be, and the other side would maybe be along the glass up on the driver’s side. Everybody would clear out of the way because this was an unsafe condition. You can’t land a body like that. That operator would slowly let that body down on the frame and it would turn. Usually those bodies were damaged. That car would go on being built just like there was nothing wrong with it. It had scrapes and dents.

But hey, if it can be built, it can be repaired. That was their theory. And they went with that. Just because it was damaged, that didn’t stop it from being made.

In Fisher they had a body bank. Something went wrong someplace so they would take this body out of the line-up. It would be set in there. He would go in at the start of his shift and look at his teletype paper. Then he would go around and check the body bank. He might have thirty cars setting there. He might have fifty bodies settin’ up in there. It was up to him to put that body, let’s say in the twenty-sixth position that had to be run that night. He would go around and number them firewalls, so he could identify it. He couldn’t remember these all night long. When that spot come up he would just roll the body on a dolly himself, easy, no trouble. He would just push it into the right spot. Now that car was in the twenty-sixth position. Not all cars had that number, but if that car had it, it was correct for that particular car. It was to convenience somebody in that plant.

When you’re talking about taking a crayon pencil or a piece of chalk and writing on something, this is not capitol punishment if you do it. If it benefits you, you’re definitely gonna do it. You’re gonna write on a vinyl roof if it’s gonna benefit you. You don’t care. It’ll wipe off. If it doesn’t wipe off, what’s it hurting?

Any numbers you run across like that, it’s right for that car. Not right by standards maybe, but right for that car. If a guy’s doing a restoration, and that number came out on there, that would be the thing to do to put it back on there. That car was born with it, and it should stay on there. If not, they’re all going to look the same.

I got back into the ’64s kinda by accident. The desire to own one had quit burning at me anyway. One day a friend of mine, Ron Chappel who’s got five ’64s and ’65s, came down. We set here and got B.S.’n about GTOs. This was 1989. All I had to do was sit down and talk and think about it, and I had the itch for one. Later on, I said, “You know Ron, I wouldn’t mind owning one of them cars again. If you find one, let me know about it.”

A little latter Ron called me and told me about the car down in Farmington Hills that I’ve got now. That was my first one. The running chassis was restored late in the 80’s, before I bought it. The rest of it I restored in ’90. I got it out of the body shop in July, and I liked the car so much, I had to get another one.

When I seen it advertised, I was setting there reading the Detroit newspaper. It was on a Friday night. I read “1964 GTO for sale.” The guy had $4,500 on it. I wondered what kind of car that is? I called him up. He lived in Chelsea, Michigan. That’s west of Ann Arbor and a good two and a half, three-hour drive from here. I talked to the guy. He told me the car was a Fremont, California car. He bought it and drove it back here in 1978. I said “look, we’re a long ways apart, tell me exactly where all of the scratches are on the car, don’t leave anything out. I don’t want to drive three hours and be disappointed.” He described the car to me completely. He sounded sincere in his voice. The next day Lee and I went down there. Took the truck and the trailer with us. As I wheeled into the guy’s driveway, I sat in the truck, looked at the GTO and knew I was buying it. It was better than what I expected, and better than what he had explained to me. And it was probably the most original ’64 that I had seen in a long time. Not perfect, but original with 56,000 miles showing on the odometer. It even had the original redline in the trunk. And I believed the odometer reading. We saw that GTO this afternoon with a fresh new coat of paint on it. It’s in the process of being restored.

WAC: Was the V.I.N. number ever stamped anyplace on the car?

CP: I think that it was stamped on the frame rail. I think that you’ll find out that there’ll be a sequence in that V.I.N. number, maybe not the whole thing, but at least say if it was the 29,337th car, on the V.I.N. number it tells you that. If you look on that frame rail and could clean it off that’s what it would be.

WAC: Where on the rail was it stamped?

CP: The body would have to be off the frame to read it. It would be where the hump in your frame went over your rear axle, and it would be halfway back on the top driver’s side, between the end of the frame and there. It was in that area. He did it on every frame. I know every frame got stamped with a number. I’m sure that the V.I.N. number on the frame matched the V.I.N. number that was on the body tag.

WAC: Were the hood hinges bare metal or were they painted?

CP: From what I remember, and I wouldn’t want anybody to quote me on this, I remember them being black. The spring was natural. Lee worked that job on the line. He says that was one of the least favorite jobs in the plant. Because it was so dirty they wore gloves to keep the oil coating from the hinges off of their hands. Even then, their clothes got pretty dirty by the end of the day. The springs were natural.

WAC: What about the coil springs?

CP: You might get on the production line and have springs that were bare, then you might get two shipments that’s got black on them. Those springs would always come paired. Nobody can sit down and say that every car came with a bare spring, or every car came with a painted spring. Those shipments might have come through for six months without paint on ’em. Then all of a sudden they had a bunch of ’em that they had stored outside, and they painted them so they could store ’em outside, and they didn’t all just turn into rust. The springs that I remember definitely weren’t painted. They had tags on ’em, and they had color paint on ’em. I don’t remember what them color codes were. The springs came from the supplier with the tags on ’em.

WAC: Where did the bodies get painted?

CP: The bodies came right out of the Fisher Body plant already painted. They come over on a conveyor right through a hole in the wall.

WAC: How were the spray guns set up?

CP: They had hoses comin’ right out of the wall. There was a gun attached to each hose. They’d just reach back and grab the right color, spray it, and when they got done they’d set it back and get the next one. It was just rollin’ right along. That paint was from a completely different drum of paint from the one used in the Fisher plant to paint the bodies.

WAC: How were they trained?

CP: Say you’re the new guy in here. You walk right in. “You watch me son. This means this. O.K.? This next group of parts comin’ up here is for a red car. This guy across the line, he knows, he’ll tell ya you need red. You turn around you get your red gun. You watch me and I’m gonna show you how to paint. You get in here and you get your movement. And then you pull the trigger back here.” You stay exactly a foot away; you stay exactly eight inches, whatever it was. “You go right down through there. You’ll see the shine on that, and you keep that shine on there. If you run it, you tell us that you screwed this up. If you want to keep your job you won’t screw up too many of them. If you don’t want it you just keep messin’ up.” He was spraying a customer’s fender the first time he pulled the trigger on a gun.

I used to go up there a lot, even when I didn’t know anybody in there. I’d just walk in there and watch them sprayin’. And I don’t remember them guys wearing masks. They had that waterfall right behind them. You could just take that gun, hold it out there and hit it, and everything would just go down. That water would just pull the paint to it.

The racks got a coating of paint every time they went through the booth. Once every six months or once a year they had to clean ’em off. The jigs were made from like a 3/4″ rod, and after a time that rod would be swelled up to an inch and a half thick with paint. They’d put them in a walk-in freezer and freeze that down to thirty below zero. Then a guy would take that out of there and he’d hit it with a hammer. That paint would just fly off of there; chip off like broken glass. Some of those guys would get those big chips of paint and they’d sand ’em down to make pieces of jewelry. A lot of people made ear rings, necklaces, arrowheads. If you didn’t like the design on it, just sand on it with 600-grit paper and water, and it would change. When you got it where you liked it, you’d rub it out and wax it. I never made any of them things. I was just never interested enough to do it.

WAC: In 1965 they started pinstriping the GTOs. That had to have been done after the car was put together.

CP: That was done in Plant 16. When they first started to do that they tried to do it in Plant 8. They found out that it didn’t work there. Too many people were leaning on the cars before the paint was dry. They finally moved it right out of there.

WAC: Did the seats have plastic covers on them while you guys were working in the cars?

CP: No. There were no covers on the seats. The bodies come out of the Fisher plant with the seats already bolted in the car. They put plastic over the seats; it was like a real light plastic, you know, you could just tear it off. That was just prior to shipment. Prior to going to a dealer. As far as in the plant goes, the seats were never protected. They were just exposed.

WAC: Where were the electrical checks done? Things like the headlights, taillights, and radio.

CP: That was taken care of down on the return line where the roller drums were. When the guy got in it and run it, he started that car, and he did that then. He had mirrors hangin’ in the front and back so he could see if all the directional signals were working, the brake lights worked, the headlights high and low beams, he’d blow the horn, turn the radio on, but I don’t know about air conditioning. Somebody must have checked that, but I don’t know where.

WAC: Were there ever any accidents in the plants?

CP: Hell, I knocked a quarter panel out of more than one car. The plant was full of steel support beams. Big twelve-inch square I-beams. In ’65 or six they went around and painted every one of them beams a bright color. They were painted pink, orange, white, blue, red, to try to liven the place up, to try to cheer it up a little bit. They also did that to make them beams highly visible so people didn’t hit ’em, and doors didn’t get opened up into ’em. The beams were like twelve feet apart, and the line would run in between ’em. If you left the door wide open, when it went by, that beam would have like a rubber pipe covering on it so that when the door hit it, it would close it.WAC: Ever see anything spectacular, like an engine falling off a hook?

CP: No. I never saw one of them fall. It probably has. Anything can happen in an assembly plant. I was only there during one shift a day, but I never saw anything like that. WAC: On the firewalls of some of the cars you see now days, you find a two-digit number scratched in chalk pencil. Any idea what that stood for?

CP: I would guess that was put on by an employee for his personal reference.

WAC: What was the most unusual car you ever saw go down the line?

CP: It had to have been a ’64 or ’65 Bonneville; a 421 tri-power, four-speed, bucket seats with 8-lugs. It was a station wagon and it was painted a bright pink!

WAC: When did you leave Pontiac Motors?

CP: In the middle of ’69. Probably within four or five months into the model year.

WAC: Was The Judge in production by that time?

CP: Yes. When we saw the first ones coming down the line we thought it was some kind of a joke. I thought it was the ugliest thing Pontiac had ever built. But since I’ve been helping Lee with his ’69 GTO here in the last year, the style has sort of grown on me.

WAC: After you left Pontiac Motors where did you go?

CP: I went to Travco Motor Homes, building motor coaches. I was a welder out there. It was closer to home, Brown City as compared to Pontiac. It seemed the thing to do at that time. It was time to raise a family. I got married and sold my car, and my daughter was born in ’68. Sold my ’65 Goat in late ’67, and bought a ’62 Ford 292, three-speed, two-door sedan. Worse car I ever owned in my life. That’s what I replaced the GTO with, a family car.

WAC: Today you again own GTOs?

CP: I’ve got five now. One of ’em’s a parts car. Probably one more should be a parts car, but it’s not gonna be. One’s restored; that one’s a Grenada Red ’64 with black interior. Like my first GTO, the only difference being an automatic on the column as compared to a four-speed. I’m not into four-speeds any more. I like my automatics, I like to drive ’em. I enjoy ’em. As you can see by the trophy, I won third place at the Woodward Avenue show down at Domino Farms last summer.

WAC: Why did you decide to get back into GTOs?

CP: I never lost my love for them cars. It never left. It never wavered. I never quit looking at auto swapper magazines. I was always looking for the dirt-cheap ’64 that I could afford to buy.

I just picked up a ’65 coupe. It come out of the U.P. of Michigan, and originally came from Tennessee. It’s a 2-door sedan with tinted glass, four-barrel, and automatic on the column. It’s in rough shape, but I can’t let it go down. I’m gonna restore it.

I’ve got a ’74 hatchback. The interior is rough. The outside is what I’d call rough. It don’t look bad. It runs great. It’s kind of a fun little car to drive. It’s a four-speed, and I don’t have any plans for keeping that car. That one I could part with in a heartbeat.

My fifth GTO is a white ’74 notchback or coupe, that’s strictly a parts car.

Thus ends a view of the operations at the Pontiac assembly plant during the mid to late 1960s era. I hope that you enjoyed getting a feel for what it was like putting the cars together at that facility, and maybe this series of articles has cleared up some of the questions you may have had concerning how your Tempest, LeMans, GTO, Bonneville, Catalina, or Grand Prix was “Made in Pontiac.”

I would like to acknowledge and thank the following persons, without whose help this article would not have been possible: Carl Papke, John Sawruk, Rick Remer, Lee Chapel, Ron Chappel, Nate Thomas, and Dennis Bahling, Mike Woody, Keith Seymore.

Made in Pontiac PT5 Image 1

Front end sheet metal exits the spray booth, makes a right-hand turn, then, traveling away from the camera, enters the bake oven on the third floor

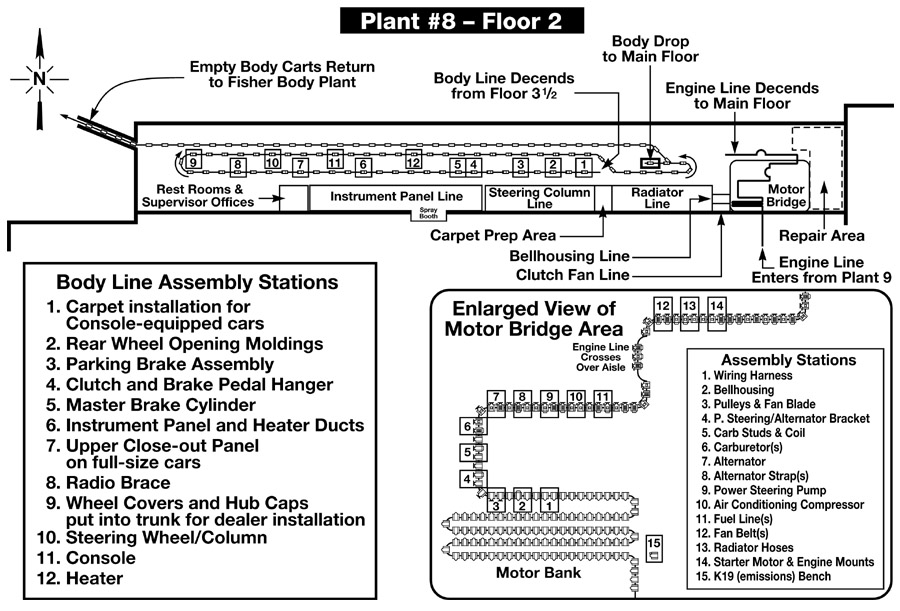

Made in Pontiac PT5 Image 2

Near the front of the plant, sat this display of assembled front clips. Each year the display was updated.

Made in Pontiac PT5 Image 3

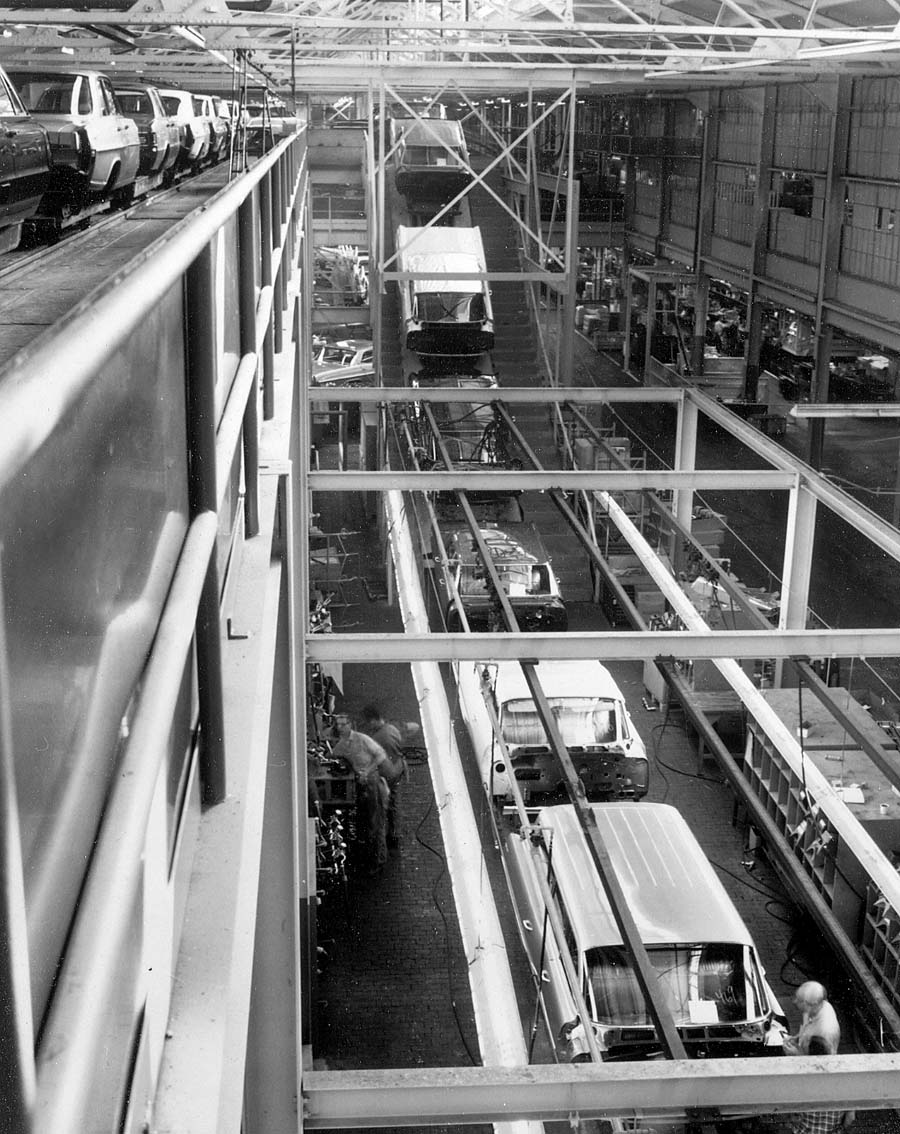

Looking down from the third and a half floor balcony. Cars drop to second floor via the “ski jump,” seen at the center top of photo.

Made in Pontiac PT5 Image 6

Here is a spot near the steering column installation station. Note tree of steering wheels on far side of line.