Jim McCuan wants to get into the 200 MPH Club

with this 1964 Studebaker Hawk and a Stude V8!

With grit and determination – and a ton of ingenuity – almost anything can be done.

We’re betting 200 MPH is a possibility with Jim’s energy and efforts

by Jim McCuan and Society Staff – Reprint with permission only

We are preparing a 1964 GT Hawk to run in C/CPS at Bonneville. Having spent a couple of years acquiring the basics, it’s time to move toward more specific items. The requirements of the class require, in this case, a production supercharged coupe or sedan from 1928-1981 running 306.0 to 372.99 cid. (Yes, the Avanti has a superior shape, but later plans for the car after Bonneville will be better for a Hawk, plus, plenty of other folks are representing Studebaker on that Avanti platform).

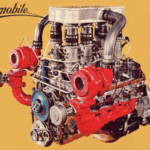

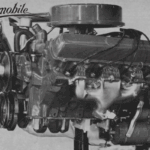

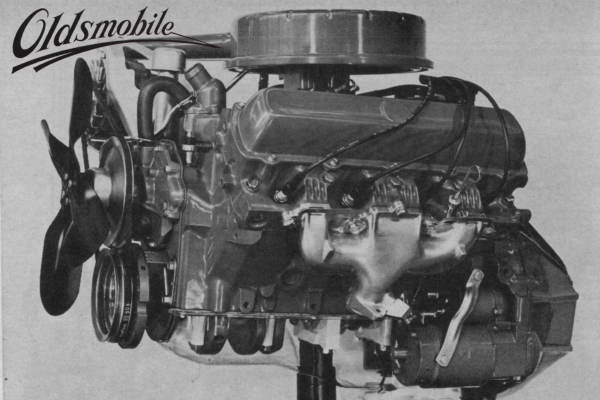

The engine will be a 1959 Studebaker Partial Flow 259 Block. (All Studebaker blocks will usually accept the same reciprocating assembly, hence there is no need for a 289 or R-Series 304 block). The secret to my engine is a special stroked 289 crank that tops out at 4.25″ vs. the stock 289 stroke of 3.625″. The crank was stroked back in 1963 by Andy Granatelli’s shop – apparently for a shot at some records in their Bonneville R-3 Lark. The engine ran for only a short period of time and apparently chewed up the special cam they ground for it – all else is good.

We’ll spend more time on the engine build in a later installment, but suffice it to say that whatever you are building for a record run like this has to be bullet-proof and able to sustain your max RPMs for a good deal of time. Hence, the build cannot overlook a single detail. The question is -can a Studebaker block handle what we intend to dish out? Hopefully, you’d be as intrigued as the Wild About Cars staff was to see if it could be done. (we think so, but you can judge from later installments).

The original Granatellli R3 and R4 engines had improved heads. The intake ports were opened dramatically. Larger intake and exhaust valves were installed which required moving each pair of valves away from one another and notching the engine block for clearance and increased airflow. The R3 heads quickly became sought out by engine builders seeking big performance gains

The Bonneville motor needs to breathe, however a set of real deal rare R3 heads were out of the budget, so the quest began for something just as good or better using conservatively priced components. An engine builder in the Atlanta area was taking common Studebaker heads, welding on more material where needed, and matching them to the R3 intake manifold. And the chambers featured R3-sized valves. With a lot of grinding and cutting the ports on these heads promised R3 performance plus . . .