Why the Boss 302 – Ford’s “Tunnel Port” Missed the Mark

Ford’s experimentation with the 302 Tunnel Port (TP) engine is a fascinating chapter in automotive history, highlighting both innovation and the challenges of performance engineering. Let’s dive into the intricacies of this engine and why it ultimately didn’t make the cut.

The Genesis of the 302 Tunnel Port

Ford’s TP 302 was an ambitious project aimed at enhancing the performance of the “Windsor” small-block engine family. Unlike most engines that saw street use, the TP 302 was designed with racing in mind. Its notable moment in the limelight was in a road test Mustang loaned to Car and Driver magazine for a head-to-head against a 1968 Z/28 Camaro.

Design Philosophy

The 302 TP shared a design philosophy with the 427 TP engine. The key innovation was the use of sleeves to house the pushrods, allowing for larger intake ports. This design aimed to increase the volume of the fuel-air mixture flowing into the engine, providing a direct path to the intake valve. The TP 302 boasted sizable valves—2.12″ intake and 1.54″ exhaust—and was equipped with two 540-cfm Holley four-barrel carburetors.

The Downfall: Performance vs. Practicality

While the TP 302’s design was theoretically sound, practical application revealed its flaws.

Overly Large Ports

The TP heads had ports that were too large for effective use at lower RPMs. To generate power, the engine had to be revved up to 8,000-9,000 rpm, which was impractical and risky for the 302’s bottom end. This high RPM requirement led to poor performance and reliability issues in the SCCA Trans Am Series. As a result, race teams preferred the older, more reliable 289 engines despite their lower power output.

Unreliable Performance

The TP 302’s high RPM demands made it a poor fit for both racing and street applications. Its disappointing performance and unreliability were evident by the end of the racing season, prompting a return to the tried-and-true 289 engines.

The Rise of the Boss 302

Ford’s solution to the TP 302’s shortcomings was the Boss 302, a high-performance engine that became a legend in its own right.

Design and Development

The Boss 302 was introduced in the 1969 Mustang Boss 302 and the 1970 Mercury Cougar Eliminator. To compete in SCCA’s Trans-Am Series, at least 1,000 Mustangs needed to be equipped with this engine. Production exceeded this requirement, with 1,628 units in 1969 and 7,013 in 1970. Additionally, 450 Cougar Eliminators were Boss 302-equipped in 1970.

The Heart of the Boss: Cylinder Heads

The Boss 302’s major innovation lay in its cylinder heads, which were derived from the forthcoming 335 Cleveland engine family. These heads, with modified water passages to align with the Windsor 302, featured canted valves for better breathing—similar to Chevrolet’s big-block V8.

Valve and Port Configuration

The Boss 302 heads had significantly larger ports and valves than the Windsor heads. The original valves were 2.23″ intake and 1.71″ exhaust, although the 1970 version had slightly smaller intake valves at 2.19″. These heads were also used on the 1970-1974 351C engines with four-barrel carburetors.

High Performance Features

The Boss 302 included several high-performance features:

- Threaded rocker arm studs

- Pushrod guide plates

- Stamped-steel sled-fulcrum rockers

- A special mechanical-lifter camshaft

The engine was rated at 290 horsepower, matching the Chevy Z/28 302 and Chrysler’s 340-cid small-block with triple two-barrel carburetors.

Robust Construction

The Boss 302 was built for durability with four-bolt main-bearing caps, screw-in freeze plugs, a forged-steel crankshaft (cross-drilled in 1969), and high-strength connecting rods. The stock compression ratio was 10.5:1, and it featured a dual-plane, single four-barrel aluminum intake manifold with a Holley 780-cfm carburetor.

The 351 Cleveland Arrives

The introduction of the 351 Cleveland in 1969 marked another step in Ford’s evolution of high-performance engines.

Cleveland vs. Windsor

The Cleveland engine series, though sharing bore spacing and cylinder head bolt patterns with the Windsor series, was a different beast. It featured two types of cylinder heads: ‘4V’ for four-barrel carburetors with large ports and valves, and ‘2V’ for two-barrel carburetors with smaller ports.

Distinguishing Features

The Cleveland engine had a distinctive design:

- Square-shaped rocker cover with 8 securing bolts

- Integrated timing cover casting

- Different radiator hose routing compared to Windsor engines

Performance Variants

The Cleveland engine came in several high-performance variants, including:

- H-code 351: Produced from 1970-1974, this 2V engine had lower compression and was used across various Ford models.

- M-code 351: Produced in 1970-1971, this 4V engine had higher compression (11.0:1 in 1970, 10.7:1 in 1971) and more horsepower (300 HP in 1970, 285 HP in 1971).

- R-code Boss 351: A 1971 high-performance variant with 330 HP, featuring four-bolt main block/caps and modified cylinder heads for better airflow.

- Q-code Cobra Jet 351: Produced from May 1971-1974, this lower-compression design included open-chamber heads and different intake manifolds.

The Legacy of the Cleveland Engine

The 351 Cleveland continued to evolve, with various models tailored for different performance needs. It found a unique place in both American and Australian automotive history, with Australian-built versions used in DeTomaso vehicles long after American production ceased.

The TP 302’s failure was a stepping stone that led to the creation of the Boss 302 and the 351 Cleveland, both of which left a lasting impact on Ford’s performance legacy. These engines demonstrated Ford’s commitment to innovation, even when initial attempts didn’t hit the mark. The lessons learned from the TP 302’s shortcomings ultimately contributed to the development of some of the most iconic engines in automotive history.

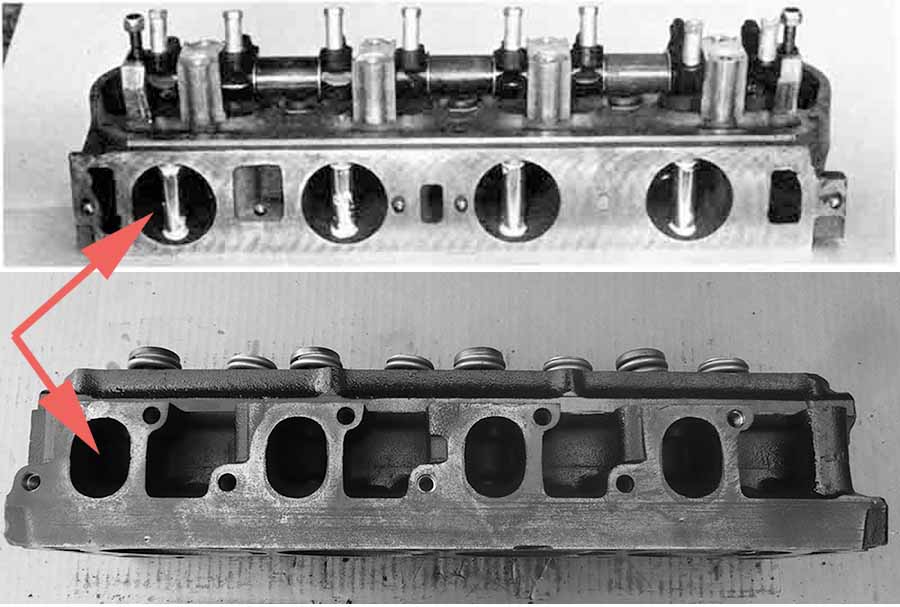

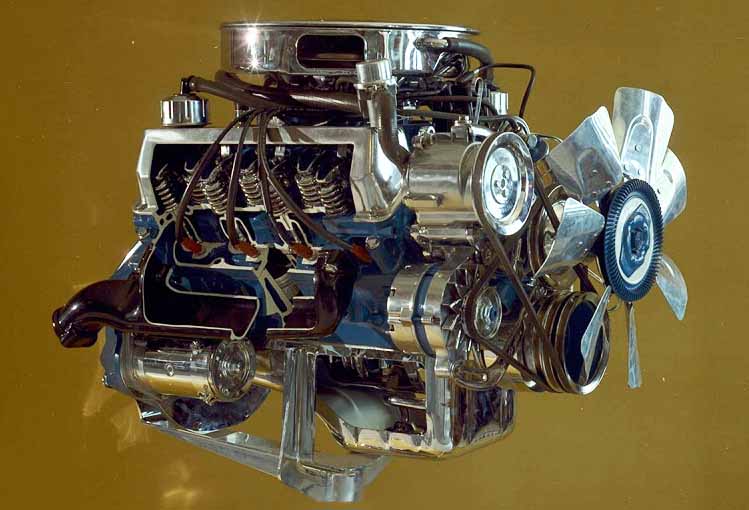

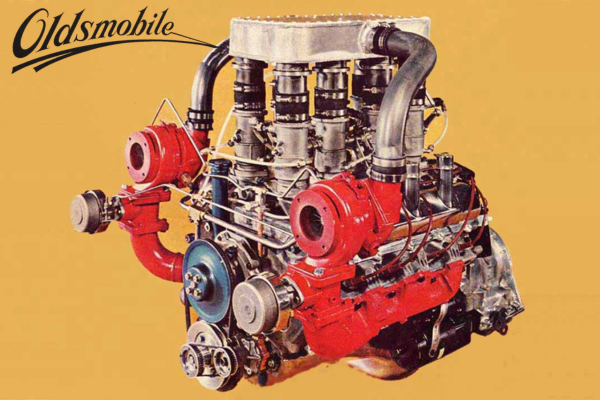

Cleveland Image1

The Boss 302 both revitalized and redefined small block performance at Ford in the 70s.

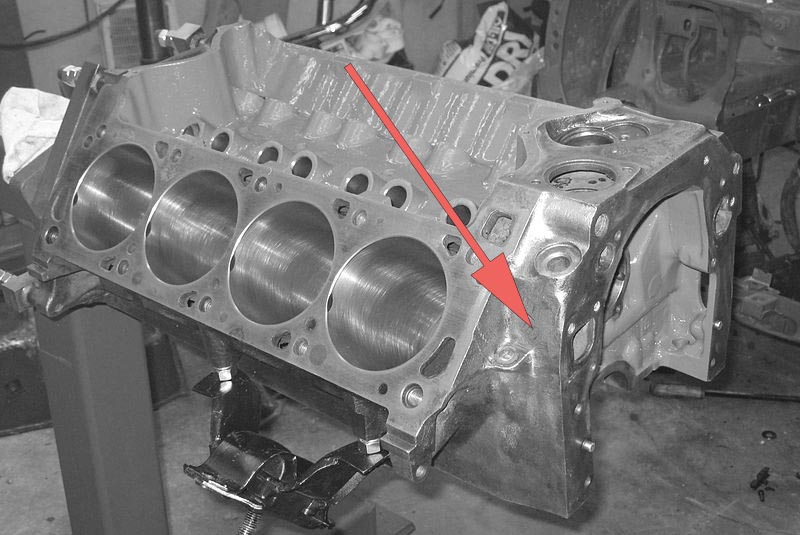

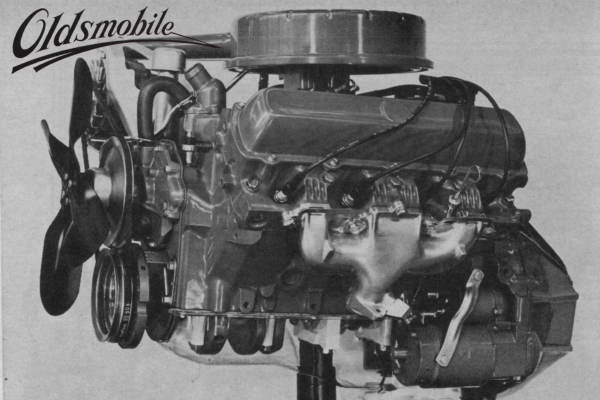

Cleveland Image3

The cast-in front cover easily identifies a “Cleveland” block versus the Windsor Series.

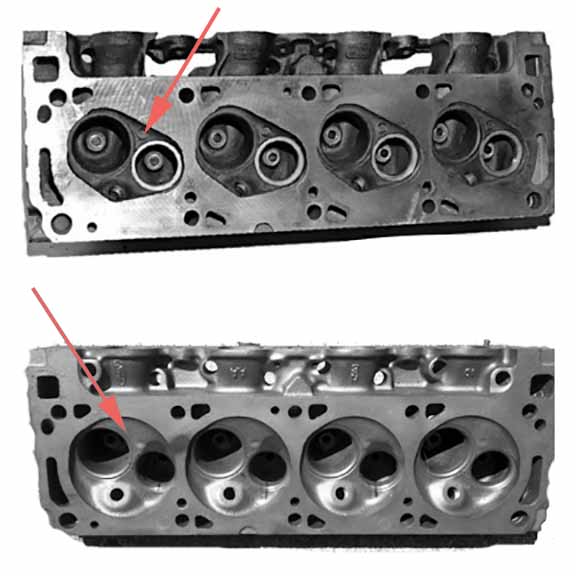

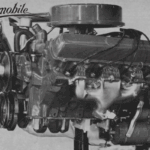

Cleveland Image6

This image shows the differences between the closed chamber Boss Heads (top) and the Open Chamber 351 “R” and “Q” code (and the 2V) heads (bottom)